Follow us on Facebook @FHofDW

Deal’s Early Freshwater Schemes

The Water Schemes in Practice

It appears that Warner and Ryder both then supplied the town with water via their different schemes. But how?

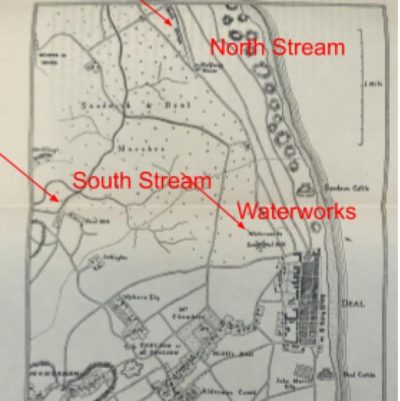

Historians have said that water was taken from the North Stream via a water pump that was driven by a water mill to lift water to a sufficient height so as to feed water by gravity to all parts of the town. We are also told that a brick built building, on the property of the Cannon family, was erected for this purpose and bored Elm log pipes were used. Likewise historians cite the North Stream in the discussion held at the Three Kings Tavern in 1702. So this all seems to point to Ryder’s scheme as it was he who proposed to use the North Stream.

Presumably private subscribers had their own ‘reservoir’ to enable them to have water pumped in or near their homes. In later property descriptions in the newspapers and deeds water pumps are mentioned. Could these originally have been part of Ryder’s scheme?

So far though we have not been able to find any references to water being taken from the South Stream as proposed by Warner. His scheme was based on wells and we know of several including The Bear Pump, near the Town Hall, one in St. Andrew’s Rectory, another on St. Andrew’s Road and the old Swan Public House. Are these Warner’s Wells?

The letter dated 22 May 1701, that was sent to Earl Romney Henry Sidney, tells us that Warner had plans to dig what he called a ‘receptacle’ to “…hold a quantity of water with wood pipes from the South Stream, at Pinnocks Wall to the well and from thence ….to a cistern intended to be in the middle of the town for general supply…” The South Stream we are told was “…one mile and a half from the towne and the other called the North Stream three quarters of a mile distant from there…” The letter goes on to say that three further Conduits will be erected “…in such places as the Mayor and Jurats shall think fit…” Whether any of this happened we just don’t know.

How successful either of these schemes actually were is in doubt. Deal, though growing, was a small town and the water being proposed was being brought at least a mile before it actually reached the town. Added to which the available profits would have been somewhat reduced by having the two schemes running.

How successful either of these schemes actually were is in doubt. Deal, though growing, was a small town and the water being proposed was being brought at least a mile before it actually reached the town. Added to which the available profits would have been somewhat reduced by having the two schemes running.

We know from a letter at The National Archives, written in 1709 by Thomas Warrin, that there were problems with the reliability in the supply of water as far as the Naval Yard. In his letter to the Naval Commissioners, he complains that “….I am the last served when it is to be had, but most winters… the pipes are frozen , and in little winds they can’t always force it up to me…” He goes on to say that he was “…frequently obliged to hire men to fetch it in…” and that as a defect in the pipes “…yet to be found..” he asked for permission to sink a well and fix a pump in it in the Yard at a cost of £20. He also requested to “..order an Engine for the playing of water in accidents of fire….”

Despite this supposed ample supply of good water most of the town’s inhabitants continued to rely on wells that were often brackish, some being contaminated by human and animal waste seeping into them. At some point public pumps were erected, probably using water accessed from one of the original schemes. Rainwater was still collected and stored in tanks or butts well into Victorian times; there are references in the newspapers to property or leases being sold that refer to rain water tanks.

Deal Water Works in the Nineteenth Century

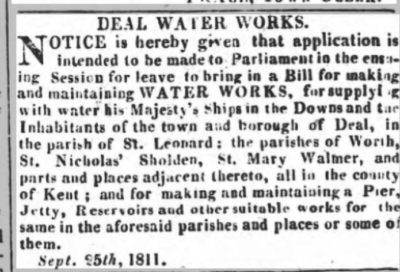

By the early 1800s moves were a foot to again provide the town with freshwater. In 1810 a notice was placed in the newspaper proposing a Bill for making and maintaining waterworks for Deal.

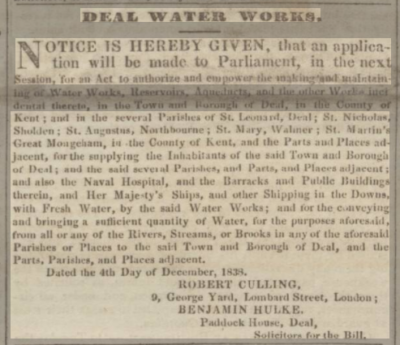

This didn’t seem to get far as by 1838 another proposal was made. This time it led to the Deal Water Act being passed in 1840. It took decades but gradually throughout the years every Deal inhabitant gained freshwater piped directly into their homes.

And now we just take it for granted that all we have to do is turn on a tap to get ‘freshwater.’