Follow us on Facebook @FHofDW

Peter Atkins

16 Beach Street, Deal

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Guernsey

Calais, France

Webb Street, St. Olaves, Surrey

83 Great George Street, Bermondsey

Occupation: Boatman, Inn Keeper, Clerk

Peter Atkins was born and baptised in Deal in 1777 and followed his forefathers in making a living from the sea, mainly by fishing and hovelling. The Atkins family originated in Ringwould though it seems that they had close links with Deal, at least from the early 1700s, but being fishermen, Deal would have been well known to them anyway. Robert, Peter’s father, seems to be the first to officially move into Deal. In 1767, after he married Elizabeth Reyonolds, the Parish of Deal agreed to let him ‘settle’ in the town.

In May 1799 Peter married Sarah Eades in St. Leonard’s Church and they set up home in Deal on Beach Street where they started their family.

Sarah Eades

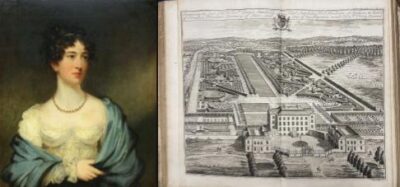

In the parish Register of St. Mary’s Church in Sundridge, near Sevenoaks in Kent, we found a baptism in 1776 for Sarah Edes (written without the ‘a’) the daughter of Samuel and Susannah. This Sarah seems to be the most likely candidate for Peter’s future wife especially as we know, from a later letter written by Lady Hester Stanhope, the young Sarah Eades found employment as a housemaid at Holwood House which is approximately eight miles from Sundridge and the home of William Pitt the younger.

Chevening Place is also approximately two miles from Sundridge so perhaps Sarah may even have worked first at Chevening Place before finding a position as a housemaid at Holwood House.

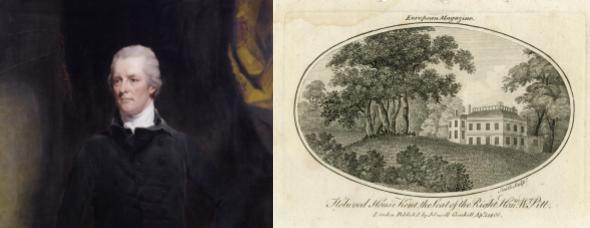

William Pitt c1804 by John Hoppner Holwood House

Peter & Sarah

The Parish Marriage Register of St.Mary’s Walmer, states that Sarah was ‘of Walmer Parish’ when she married. But how did the young couple meet and when?

From 1792 to 1806 William Pitt the younger was Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and spent a great deal of time at Walmer.

We know that from 1794 William Pitt took an active part in the Deal Cinque Port Fencibles, and that William Pitt was in residence at Walmer during that time. The drilling of these troops would have been a spectacle not to be missed.

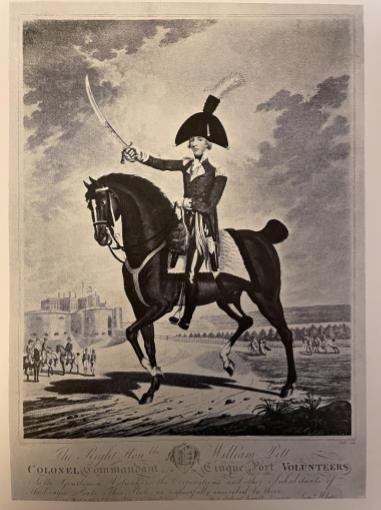

William Pitt as Colonel Commandant of the Cinque Port Volunteers- From an aquatint by Joseph C Stadler

Throughout the summer of 1799 William Pitt spent a lot of time at Walmer planning an expeditionary force to expel the French from Holland. So it is feasible, as household staff did travel with their employers, that the couple met during these visits. Perhaps knowing that the Pitt’s household would leave Walmer at some point in that year, may have prompted the couple to marry, by licence on May 16 1799 at St. Leonard’s Church, Deal.

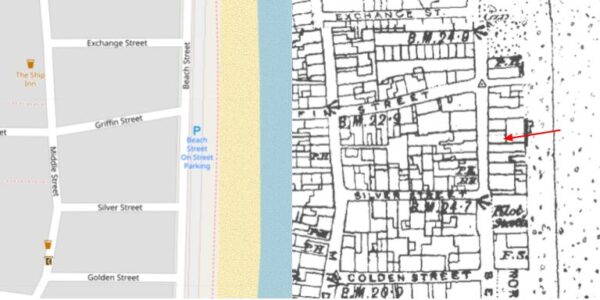

Peter, we know, had at the end of March 1799 bought 16 Beach Street. This is described as a “…messuage with outbuildings, backside and ground in Lower Deal, abutting to the sea…”. Sadly the property was demolished sometime in the mid 1920s.

War with France

This was an unsettling time with France in the grips of revolution and in 1799 Napoleon took power threatening to invade Britain. Then on May 18 1803 Great Britain declared war on France, and the Army Reserve Act was passed. This was designed to voluntarily raise an army of men, rather like the Home Guard of WW2, who would be expected to help defend the coast. When this failed to bring in the numbers required a second Act was passed in July. Known as The Levee en Masse Act which required the parishes to return a list of all men in the parish. The returns of these two Acts are known as the Lieutenancy Papers.

Peter Atkins is listed on the returns for the Army Reserve Act stating that he was already serving as a Sea Fencible. The 1805 returns for Sea Fencibles show that he was still serving and had become a Petty Officer for which he was paid 2s 6d for every day they assembled. Sea Fencibles were provided with uniforms, training and were exempt from impressment. They were however expected to use their own vessels to attack the French operating under Letters of Marque meaning that any enemy vessels they captured, once sold, the crew who made the capture would gain a share of the prize money.

Peter may well have earned some ‘prize money’ this, with his earnings from the hovelling, his Sea Fencibles allowance, and other services provided to the Maritime and Military during this time, perhaps even a bit of smuggling on the side, meant that by around 1805, he was the proud owner of a new boat called Noble.

That year he had also become a father for the third time. His first child Sarah, named after her mother, was born in early April 1800 followed by Elizabeth Reynolds, named after his mother in February 1802. Louisa was born in March 1805 and little did they know that the events of the previous month, following a storm and the stranding on the Goodwins of the West Indiaman ship,named Endeavour, would, for Peter and his family, be the beginning of decades of distress, uncertainty and desperation.

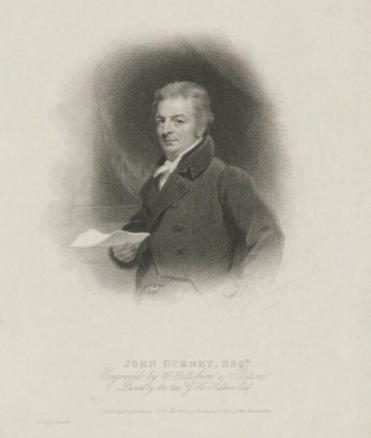

Most of the events that brought about the Atkins family’s turmoil were revealed in the trial transcript written by Joseph and his son William Brodie Gurney and printed by H Teape ‘The Trial of Peter Atkins …..’ in 1808.

Most of the events that brought about the Atkins family’s turmoil were revealed in the trial transcript written by Joseph and his son William Brodie Gurney and printed by H Teape ‘The Trial of Peter Atkins …..’ in 1808.

Joseph Gurney and William Brodie Gurney were the son and grandson, respectively, of Thomas Gurney who had established the use of English shorthand and was the first to use it to record what was said in both houses of Parliament and at the Old Bailey. Both Joseph and William continued with its use and later printed some of the notable Old Bailey trials including that of Peter Atkins.

The Endeavour

The trial transcript and newspaper reports of the day tell the story of how, at about three o’clock in the morning of February 8 1805 Endeavour, owned by Henry Wildman, was in distress off Deal and had been driven onto the Goodwin Sands. When daylight came Peter, onboard Noble with other Deal boats, seeing the ship was in need of assistance, went out to her.

Peter was the first to reach her and once on board he spoke to Captain Dickens, and they went below with the ship’s carpenter, William Mobbs, to see if Endeavour could be got off the Sands. Once below decks they found that her after-hold and bread room were full of water.

Back on deck Peter was reported to have shouted out “A wreck! A wreck!”. A call for other boatmen to come onboard with the purpose of getting as much of the cargo off the stricken vessel as was possible. To do this they broke open the hatches to enable the cargo to be removed as quickly as possible. By then other boats had reached Endeavour.

As the cargo was placed into the waiting boats the chief mate, whose name was not recorded, was ordered by the Captain to take an account of the different boats. No further mention of this appears to be recorded in the printed trial transcript by the Gurneys.

John Kneller, Henry Wildman’s agent in Jamaica, was onboard and a trial key witness. He told the court that, when the cargo was shipped at Jack’s Bay in Jamaica, he had marked Henry Wildman’s cargo of hogsheads of sugar, puncheons of rum and tierces of coffee with an E over H W. E was for Esher, Henry Wildman’s estate and HW his initials. He took obvious interest in what was happening to his employer’s cargo of goods as well as to his own, which he had marked with J.K. as they were taken off the ship.

At one point John Kneller noticed one of his puncheons of rum onboard the Noble and, thinking it was damaged he climbed into the boat to see if it was leaking. However, he was told in no uncertain terms that he had no business there and was roughly hustled out by two of the boatmen using, he said, threatening expressions!

Once the cargo was almost all taken off, John Kneller also left the ship. He was taken first in the Noble to somewhere near the shore from which, he said, Peter ordered him into another smaller vessel as “…the piads were waiting…” At this time John Kneller noticed that Peter had taken the ship’s brass compass, and he reported Peter as saying “…he was damned sorry he had not taken the ship’s ensign, which appeared to be a new one…”

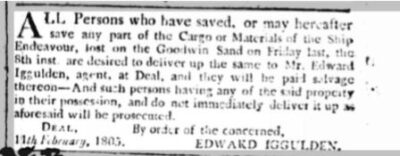

Safely on shore John Kneller took up lodgings, somewhere in the town, and according to his own testimony, he did not look or enquire after the cargo for three days. When James Wildman, Henry Wildman’s son, arrived on Sunday 10th February he found and visited John Kneller and then set about taking steps to “…procure the delivery of the cargo into the stores, offering salvage to be paid for it…” Notices were then printed and placed around the town and in the newspapers.

Having been given Peter’s address he went and called upon him to demand that he deliver to Iggulden’s, the shipping agents stores, what cargo he had kept. Being put on the spot Peter denied having been onboard Endeavour and having any of its cargo. It was then suggested that they go to the person who had informed James Wildman that he had, so they walked to the Three Kings Inn, now The Royal Hotel, where John Kneller was waiting in the coffee house there. On the way there Peter decided he wouldn’t go in without the rest of his crew!

About half an hour later Peter arrived at the coffee house with another person where John Kneller identified Peter as master of the Noble and accused him of having a thirty-gallon cask of rum and of the two tierces of coffee, belonging to him. Excuses were made but Peter eventually said that he had intended to sell the rum for Kneller in order to save him the duty! He also insisted that he did not have Henry Wildman’s coffee as it had been delivered to Mr. Iggulden.

Later that day James Wildman went to Mr. Iggulden’s counting house where , on entering he saw Peter standing there.

Almost immediately Peter said “..Well sir, since I see you can prove I have had the coffee I will give it up but if I could keep it I would…” he then said as the coffee had been distributed amongst the crew and probably sold he would pay him for it!

Counsel for the Prisoner

Mr Philip Dauncey, Barrister in law of Gray’s Inn, Mr Yates and Mr. John Gurney were Counsel for the Prisoner at Peter’s trial

John Gurney was called to the Bar in 1793 and made King’s Counsel in 1816. He was Peter’s Counsel at his Trial. John Gurney was also the son of Joseph Gurney

Mr. Yates- no information found

Solicitors for the Prisoner

Messrs. Jennings and Collier of Lincoln’s Inn. – no specific information found

When Mr John Gotty, a Thames Police Surveyor, was called to give evidence in court. He stated that on February 17th 1805, nine days after Endeavour was lost, he went to Peter’s house and searched it. In the back room he found two bags of raw sugar of around 270 pounds in weight. Peter was not at home and John Gotty stayed in the town for three days in the hope of apprehending him but did not do so.

According to the newspaper Mr Wildman, intent on capturing Peter, employed several Bow-street Officers to apprehend him, one of whom was William Anthony who also later gave evidence at Peter’s trial. On going to his house, the newspaper reported that the officers were “… beat off by a number of armed smugglers and he made his escape…” Reading between the lines of the trial evidence it seems that the boatmen did protect Peter from arrest. Violence was not unknown amongst the boatmen so perhaps the report had a grain of truth to it and not just sensationalising the story!

In court, we are told that William Anthony described how he returned to Deal in May 1807 with the “…express purpose …” of arresting Peter. He, with other unnamed Bow Street officers, and John Kneller, who they needed to identify Peter, stayed at Walmer Castle. In today’s term, they went ‘undercover’ for nearly a week. A plan for apprehending Peter was then made.

According to the newspaper report when information was received that Peter had returned to his home on Beach Street Anthony and the other officers applied to the Horse Barracks for assistance. The Commanding Officer then ordered a sergeant’s guard to be stationed near Peter’s house. A boy was called to knock on his door and the officers rushed in. An alarm was instantly given “…and several smugglers with horrid imprecations…” demanded to know the Officers business who presented pistols and said they would shoot if they attempted to intervene. Peter was then taken away surrounded by soldiers who marched him to the Barracks. He was then taken in a chaise and four to London.

There is no evidence to say if the Officers had tried at other times during the two years between February 8 1805, the night of the storm and May 24 1807 when Peter was finally apprehended , and if not why not? William Anthony in court stated that he and Peter had had a conversation, where he said “…We had a further conversation about the former thing, when I was down two years ago…”

The newspapers tell us that Peter and the Bow Street Officers arrived in London’s Newgate Prison on Sunday 24th. The following evening he was brought before Mr James Read the sitting Magistrate who decided that Peter should be committed for further examination. Peters Trial was then set for just one month later on June 26th 1807.

After the case for the Evidence for the Prosecution was given Peter was asked if he would like to say anything to the jury in his defence.

He handed a note to Mr. Shelton Clerk of the Arraigns saying he would like it to be read.

It seems obvious from the trial transcript book and other documents, that Peter was well liked and trusted and not just by the town’s people. John Atkinson, a shipmaster from London said he was “…Always the best of characters; I have always employed him and his brother when I have been in the Downs …” and Edward Atkinson a merchant in the West India trade, said Peter had “…always done my business with honesty and fidelity…” When questioned further he stated that Peter brought him out cables and anchors and purchased often things for him.

Deal men Martin Mourilyan, Richard Long, Thomas Woodruffe, Thomas Rickman of the Royal Oak and Butcher, Robert Down all travelled to London and gave evidence in Peter’s defence. All testified to his good character.

During the trial there were questions as to how many times Peter left the Endeavour with the Noble laden with cargo. John Kneller was insistent that it was three times. Pilots William Carder and Thomas Ellidge both categorically stated that only one trip to and from the Endeavour could be possible. Whether John Kneller was mistaken or suggesting that more cargo was taken off the stricken ship, and ‘disappeared’, did not really matter though. Peter was being tried for Piracy and Felony in other words what he had taken, not the details of how it was taken.

There were questions put to James Wildman, by Mr Garrow, over what cargo had been delivered to Mr. Iggulden the ship’s agent, Mr. Dauncey and Mr Gurney interjected; Mr Dauncey saying “ …the non delivery by other persons cannot affect the prisoner…” Mr Gurney continued by stating that “…How much of the cargo was saved, of course is not known, and how much was sunk he can not know…”

Mr Garrow then asked James Wildman if he knew if the compass had been delivered, to which he answered it was not on the agent’s list.

Questions were then asked about when James Wildman had last seen Peter. James Wildman answered that it was in September 1806 in the street in Deal and that Peter, far from avoiding him, actually went across and spoke to him! Was Peter unaware that he was a marked man?

It has to be said that the only vessel ever named throughout the trial was the Noble. The only boatman ever identified and convicted was Peter Atkins. Indeed from the start it seems that Peter was singled out to be made an example of, particularly it seems by John Kneller.

After the Lord Chief Justice Mansfield had summed up Peter’s case the jury retired to decide his fate. The trial transcript states that “The Jury retired for a quarter of an hour, and then brought in their Verdict of Guilty”

Peter would have stood in the dock, in irons, to hear his sentence. The Right Honourable Sir William Scott, Judge of the High Court of Admiralty read out, what to us are the familiar words of film and plays, saying – “…you will be taken hence to the place from whence you came , and from thence to the place of execution, where you are to be hanged by the neck until you be dead and may God have mercy on your soul…!”

How chilling and terrifying those words must have sounded to Peter and to Sarah who we assume was there. They would have been all too aware of the gallows just outside of Newgate Gaol where, from 1783, it had been the place of the capital’s public executions and situated right next door to the Old Bailey.

Not all death sentences passed at the Old Bailey were carried out so it has been suggested that such an announcement in court with all the uncertainty and stress already suffered was simply to terrify the convicted even more. They then had to wait to hear from the King’s Council who met with the King after each Old Bailey Session to determine their actual fates.

The Newgate Calendar, a register of prisoners held in the prison with their conviction and release information, tells us that Peter remained in the gaol for roughly another year.

This was in part because Peter had a wife and good friends who were willing to do all they could to get him a reprieve firstly from the death sentence then from deportation for life to New South Wales and all the time hoping to get his conviction overturned and a full pardon granted.

Petitions

At the National Archives we found an undated copy of a letter of petition, drawn up by Peter and his legal adviser, soon after he was returned to Newgate. In it he admits to the “…Justice of the Sentence…” but points out that had his trial taken place soon after he was originally accused, then “…he should have been able to produce many persons who were onboard the ship…who would have stated facts…in his favour…” He goes on to point out that all the crew were saved that day, by him and his companions, and to detail other services and deeds that illustrate his bravery and loyalty to the crown. These deeds of bravery and service were later corroborated in petitions written by those men who knew and had sailed with him.

Appealing for mercy was not uncommon. For some it was a simple letter written by themselves, if they could write, or a friend or a loved one pleading for mercy. Others, like Peter, were lucky to have educated friends and acquaintances who could be approached to write letters of appeal on their behalf.

The man who seemed to have been employed, whether financially or not, to approach various parties asking for them to write letters of appeal and recommendation on Peter’s behalf, was Matthew White. Quite why or how Matthew became involved in Peter’s case is not known, but he knew and had access to the very people who could be approached, including those who knew of Peter who could be asked to provide what we would describe as ‘character references’.

Petition ExcerptsA copy of Peter’s letter of petition was in a bundle of others held at The National Archives all of which related to him. These letters were all copies, made by a clerk and were confirmed by a magistrate as ‘Good fare copies’.

23 May 1807 (this date may be a clerks error as it is one day before Peter’s arrest)

E Montagu Fabian, a Royal Navy Captain, who was Peter’s commanding officer when he served in the Sea Fencibles, wrote describing Peter as a “…sober, vigilant and zealous man…”

July 1 1807

The Corporation, Merchants and inhabitants of Deal said they “most anxiously implore His Majesty’s Royal Mercy…” adding that they could add many instances of Peter’s “… humanity and loyalty…” This was then signed by sixty eight men from all walks of life living in Deal.

Another letter, sent at around the same time, was sent to The Right Honourable Lord Hawkesbury Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. The letter asks for Lord Hawkesbury’s help in Peter’s case and ends by saying his help “… will ever be considered a high obligation by those who have the honour to be your Lordships Obedient Servants…”.

The original letter was signed by sixty-four signatories.

July 3 1807

William Shepperd the Barrack Master at Deal reported how, in 1799, Peter came forward at the head of the Deal Boatmen “…in the most handsome and loyal manner to embark the troops from the Camp at Barham Downs to His Majesty’s Ships in the Downs…”

July 4 1807

John Jenkins, a Deal Mariner, sent details of how Peter in 1801, using his skill and exertions, helped to save HMS Warrior and her crew when he got the vessel off the Goodwins and piloted it to safety.

5 July 1807

Richard Canney the younger, a Mariner, had his letter sworn before Mr Hammond, the Deputy Mayor of Deal. He had also gone out to the Endeavour and once on board he offered his assistance. By then the ship was full of water and nothing could be done so the Captain told him

“… you had better take what you can to pay yourselves…” It seems more than probable that Peter had been told the same and took the compass. Soon after they left the Endeavour she broke into pieces.

July 8 1807

James Thomas was the commander of the East Indiaman ship Ponsbourne. He tells of how Peter had, on a voyage to China, jumped overboard “…at imminent danger of his life to save, and actually did save…one of the crew …named Robert Youl…”

July 9 1807

The twelve man jury who had convicted Peter were approached with evidence of Peter’s good character. Eleven of these men signed a letter saying they “…humbly recommended him as an object for His Majesty’s Mercy in consideration of the strong evidence of his good character previous to the act for which he was convicted…”

July 18 1807

Eighty Owners and Masters of vessels in the Port of London who seem to have been shown the testimonials of Peter’s good character signed a letter that ended by stating that Peter and the Boatmen of Deal “…frequently affected at the risk of their own lives without any recompense whatever and therefore calling for our gratitude , do humbly recommend hilton his Majesty’s Mercy…”

20 July 1807

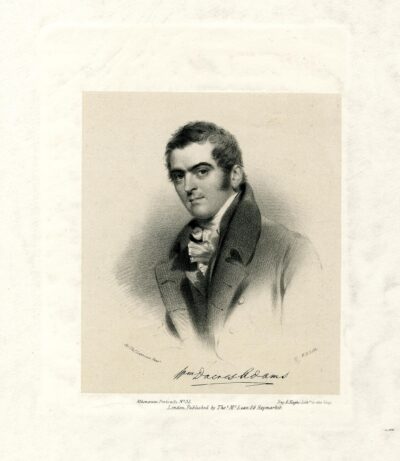

On July 20 1807 Matthew White wrote a long letter to William Dacre Adams, the private secretary to the Prime Minister. In this letter he details interviews he had with the aim of garnering support for Peter saying he “… had a long conversation with Mr Jenkinson MP for Dover who had been applied to by 2 to 300 or so of his influencing constituents asking him to use his endeavours to attain the object of Peter’s petition…” He then stated that he had pointed out several matters that he considered would be of use to Mr Jenkinson to apprise Lord Hawkesbury of them.

He tells Adams that he was “most anxious” that he should avail himself of any opportunity to ask the Privy Council to seriously consider Peter’s case. He goes on to say that it was evident that the offence of which Peter had been convicted had never been considered by any of the Boatmen along the coast as a “..felonious act…”

He also points out that because two years had passed most of those onboard Endeavour, who Peter had helped save, were not to be found to give evidence and details what the other petitioners had put in their appeals for Mercy.

He said he personally waited upon the Jury saying that eleven expressed a strong desire that Peter was to be saved and signed the recommendation for Mercy.

Matthew also went on to say that he had found out that William Edwards of Coleman Street, the twelfth Juryman, who didn’t sign the recommendation for mercy, had seen Mr. Wildman and that he also intended to see the Judge of the High Court of Admiralty Sir William Scott. Lastly, he had found that he was an underwriter for Lloyds and a subscriber to Lloyds and that the committee had paid Mr. Wildman the expenses of the prosecution. He asked, “ …Do you think such a person a proper Juryman…? The committee at Lloyds had sent a letter opposed to Peter gaining a Pardon saying that unless “..this man suffered it would be useless for them to prosecute for any offence…”

He pointed out that it may be politic for the Government to be conciliatory and keep the good will of the 3 or 4,000 active loyal Boatmen round the Exposed coast who they would need to help defend the coast against France.

He told Adams that he had interviews with Lord Hawkesbury, His Majesty’s Secretary of State for the new Home Department. Matthew White it must be said worked hard on Peter’s behalf.

23 July 1807

Peter then sent a note, from Newgate Gaol, to Mr. Rich of the Jury thanking them for the recommendation of Mercy. He offered his sincere and grateful thanks to him as, in conjunction with some other applications, it had been granted the day before.

March 3 1808

Testimonials were sent and signed by twenty- nine Merchant Ship owners of London,

March 9 1808

J A Newman the Newgate Keeper certified that Peter had conducted himself with the greatest of decency and propriety during his confinement from May 27 1807

Peter’s death sentence had by then been transmuted, to transportation to New South Wales for life, so he appealed again to His Majesty. He asked that instead of being transported for his whole life that he may be “…permitted to transport himself for a limited number of years or may remain in prison for such a time as Your Majesty shall be pleased to direct…”

He would have been presented with all these testimonials to read and approve, which he obviously did, he then sent a further letter stating that he could “…procure satisfactory security to the amount of one Thousand Pounds for his future good conduct…” In today’s money that is over £46,000. Where this money came from we don’t know perhaps his supporters had collectively offered their aid or even a wealthy, anonymous, benefactor.

A further letter was addressed to The Right Honourable Robert Banks, Lord Hawkesbury, His Majesty Secretary of State for the Home Department. This was signed by eleven MPs imploring for an alleviation to his sentence to an imprisonment or to permit him to transport himself and purporting to give ample and satisfactory security for his good conduct.

July 24 1808

All these letters, or testimonials, were then taken to Edward Marshall JP for Westminster who signed and declared

“… that these copies are now sworn to for the satisfaction of the said Peter Atkins

and that these strong testimonials of very good character may hereafter prove useful to him

London July 24 1808

Signed Matth’w White

Sworn before me at no. 38 Craven Street Westminster Middlesex

Signed Edward Marshall J. P. Westminster”

Appeals for Mercy were not uncommon during this time, so you’d expect appeals from Peter’s peers and even the borough and parish officers who wouldn’t want to be saddled with the possible care of his wife and children if they required parish relief. It does seem unusual to us that the Jury, who after all had convicted Peter, would make such an appeal not to mention the ship owners and masters and eleven MP’s!

However, courts did not operate in the way that they do today. Often evidence was hastily gathered together and trials often lasted a matter of hours not days. In fact Peter’s trial lasted five hours. Appeals then, as today, could help gain time to gather and provide evidence.

While Matthew White was actively seeking petitioners for Peter, it seems that Sarah had approached her former employer Lady Hester Stanhope.

Lady Hester wrote a long letter to Lord Lonsdale in May 1808 appealing for him to approach his nephew Lord Westmorland who was the Lord of the Privy Seal.

She points out that Peter was no more guilty than any other man on Deal beach “…who after saving the lives of persons wrecked at the peril of their own and restoring their cargo except about a tenth part which they generally keep to pay themselves…which has been the received practice for more than a century upon the coast…” and told Lord Lonsdale “…I have now a letter by me signed by above 200 boat owners at Deal thanking one for having applied to the Duke of York last year to save the life of poor Atkins…”

She goes on to say that it was Peter who “.. took Mr Pitt out to sea and who most assisted him in all his plans about arming the beach…” Hester then says that Peter was the man “…who married the beautiful housemaid at Holwood House…”. Lord Lonsdale, therefore, must have visited Holwood and seen and perhaps commented on Sarah’s beauty.

It is also obvious from this letter and from other sources that Hester had a deep dislike for Lord Hawkesbury and William Pitt’s successor as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. She calls him cold hearted and disgusting and was wanting to persecute Peter in the hope of gaining popularity with the underwriters at Lloyds.

Hester suggests that Lord Lonsdale contacts Mr Rice of Surrey Square, Kent Road as he would be able to inform him of the whole story. Mr. Rice was known to Hester as he had gone abroad with her brothers from Walmer.

It seems, too, that she even visited Peter in Newgate accompanying Sarah. Hester adds a postscript to this letter saying she had

“…witnessed the scene in Newgate I was personally at, the poor woman determined to follow her husband and the struggles of both when they were undecided whether to part with their children forever or ruin their future prospects by taking them to Botany Bay…”

Hester in July 1808 was in Abervergeny from where she wrote again to Lord Lonsdale to express her thanks for his “…great kindness about poor Atkins…” She then asks him if it were not too much trouble for him to ask the Lord Secretary for information about what future steps could be taken “… then a certain upper secretary may feel unable to break his word….” The “certain upper secretary” being Lord Hawkesbury. She ends by saying “…Atkins poor wife and children will bless you for your humanity…”

Then on 28 June 1808, on behalf of His Majesty signs a letter granting “…Mercy unto him and grant him Pardon for his said crime on condition of his quitting this Kingdom within Ten Days from the day on which he is discharged out of Custody … and not return to our Kingdom for and during his natural life…” included is the line that says “…and depart for the Brazils…” The petitions made by Peter’s supporters and the appeals for help that Lady Hester made seemed to have reached the right ears and Peter was given a job with the British Consulate Brazil. Nonetheless, Peter was being banished for life.

By Friedrich Hagedorn Vista do Rio de Janeiro & Baía de Botafogo (Botafogo Bay).

We don’t know when Peter sailed to Brazil but he was employed in Rio De Janeiro as an issuing clerk for the British Consulate. The British Consul there at the time was Sir James Gambier who had taken up the post in May 1808.

Peter was to remain in Brazil for two years but, it seems he was desperate to get back to Sarah and their children. Early in 1810 Sir Sydney Smith made another appeal for mercy on Peter’s behalf. His letter does not survive, but the acknowledgement of the reply sent by Mr R Ryder Recorder of London is recorded. This says that Ryder found Peter’s case had been so “…materially considered…” that he did not feel himself justified in his Public Duty to apply to the King to allow Peter to come home.

Peter must have met or approached Sir Sydney and others during his time in Rio de Janeiro, petitioning them to help him gain a pardon so he could return home, as Mr Ryder’s record mentions “…several inclosures in favour of Peter Atkins…” with that of Sir Sydney’s own letter.

By November Peter took matters into his own hands and on November 26 1810 Sir James wrote a letter of good conduct stating that Peter had conducted himself with “…honesty and sobriety…” during his two years in his service “…and that he is now discharged therefrom entirely at his own request…”

We don’t know when Peter arrived home but the trading ships that regularly crossed the Atlantic, took anything from five to eight weeks to do so. In December 1810 one arrived bringing news of a revolt and arrests in Rio de Janeiro. With such unrest and being so far from home Peter may have decided that it was time to take a risk and leave.

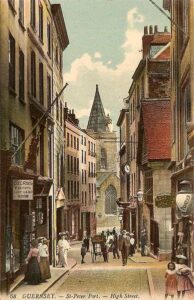

Peter spent time on Guernsey and perhaps it was here that he first landed. Perhaps too it was on Guernsey that he and Sarah were reunited. Wherever it was that they met it must have been before October 1811 as on 17 June 1812 a son, Thomas Saffrey Atkins was baptised in St. George’s Church, Deal.

If Peter attended his son’s baptism he must have returned to Guernsey soon after as, by September 1812, the house on Beach Street was sold to John Bedwell for £502. 10s and witnessed by Jurats of the Royal Court of Guernsey. It seems then that he had realised that he may be away from his homeland for quite sometime to come.

Three more children were to follow. A son, Peter, was born on Guernsey on November 19 1813 he was baptised on the same day at Town Church, St. Peter Port there are no further records for this son so sadly we don’t know what happened to him. A daughter, Mary Anne was also born on Guernsey on 25 March 1815 she too was baptised in Town Church on 19 April 1815; a last child, Susannah, was born in Calais where she was baptised on November 22 1819.

It was in Calais that Peter, Sarah and their family spent many years in exile, but Peter never gave up wanting to return home but to do that he needed that pardon. He must have tried again in 1819 as this was recorded in the Register of Criminal Petitions, this too failed as we found a letter that he had written, dated 1820, from Calais to the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth, in which he, in his own words, “…most humbly expresses his contrition and sorrow for the offence he has committed and is fully sensible of the justice and propriety of the prosecution which he has undergone…” He goes on to plead his case saying that he has a wife and seven children to support and was “…completely ruined in circumstances…” and wanted to return to his native country.

The Consul General for Northern France, Mr Fontlague, sent a letter to certify that Peter in the five years that he had been in his conduct had been exemplary and correct. This petition also failed.

He didn’t give up in 1823 he appears yet again on the Register of Criminal Petitions. Then on August 5 1825 a letter was sent to Lord Sidmouth from the dignitaries of Deal appealing to him to take Peter’s case into consideration “…on this joyful occasion of His Majesty’s Coronation…” and recommend Peter “…as a fit object for His Majesty’s most gracious pardon…”

Peter by now must have been losing hope. He’d been convicted in 1807, banished to Brazil in 1808 and living in exile since 1810 and had made at least five petitions of mercy that involved approaching others for their support.

Then on December 5 1827 Peter received a Free Pardon which said

It had taken him and his many supporters twenty years but now he could finally return home a free man. You can but imagine the joy and relief that Peter and Sarah must have felt at such long awaited news. We don’t know when Peter and his family actually arrived back in England or where they first set up home. It is fair to say that they must have visited Deal at some point. He did after all not only have family there but lots of people to thank for their ongoing support.

We do know that in 1837, when Thomas Saffrey married in Faversham, Peter said his occupation was an Inn Keeper but we don’t know where he was living at the time. The 1841 census tells us that Peter and Sarah were living in Webb Street Bermondsey and that Peter’s occupation was a Messenger.

We found a reference which showed that Peter had paid the building insurance for 75 Tooley Street on January 3 1842. This was the home and business address of Peter’s daughter Mary and her husband Peter Tagg. The reference states that Peter was a Slop Seller ( Model) ,Tailor and Draper however, these were the given occupations of his son in law. Peter Tagg was having business difficulties and went bankrupt the following year, so this probably accounts for Peter paying the insurance.

Model Slop Seller– a person who traded in human urine but was also a person who sold old clothes . a slop tailor was a person who made new clothes from old ones.

Peter and Sarah moved to 83 Great George Street in Bermondsey and it was there that tragedy struck. In February 1849 Sarah died, she was seventy-two years old. They had been married for fifty years. She had stood by him before, during and after his trial, was prepared to travel to New South Wales with him and then she followed him into exile where she brought up their children. Peter must have been devastated.

By 1851 Peter was seventy-four years old and had become a Clerk in the Court of Bankruptcy; when the census was taken in that year, he had his granddaughter, Susannah Tagg living or at least staying with him.

At some point Peter returned to Deal, perhaps it was to attend his cousin John’s funeral in March 1855, or perhaps he just wanted to visit Deal one last time. He was then, after all, seventy-eight years old. Whatever the reason Peter died of Bronchitis in Lower Street, Deal and was buried in St. George’s Church on August 17 1855. His death certificate, which was unusually dated two days later on the 19th of August, tells us that William James Smith was present at his death. William, a Professor of Music, lived at 105 Tooley Street London. So why it was William who was recorded as being present we don’t know. It is possible that other family members were there too and that William, as a friend had joined the family and was the person who informed the Registrar of his death.

The newspaper paid one final tribute to Peter calling him a “worthy man”

No head stone survives for Peter so there is no tangible memorial to this remarkable man, to remind us that overcoming adversity can happen and that love can survive all.

As for Peter and Sarah’s Children we have not been able to find out about Sarah, Elizabeth Reynolds or Esther Susannah. They could have married, and or died, in France but no records have so far been found.

Robert Eades married Mary Ann Johnson in Canterbury in 1839. At some point he returned to France settling in Boulogne where they raised their family. There he worked as a clerk, later becoming a Shipping Agent. He died in Boulogne in 1895.

Thomas Saffrey married Kate Eliza Gordelier in Faversham, in August 1837. He too, as already said, was a clerk. Their first child was born in Canterbury. By 1844 He had become a Surveyor of Taxes in Leicester where their next three children were born. They then returned to Bermondsey where a fifth child was born. Two further children were born in Ireland before they once again returned to live in Southwark which is where Kate Eliza died in 1879. Thomas Saffrey retired to Croydon where he died in 1888.

Given both these men’s occupations it seems that throughout their time in exile Peter and Sarah made sure their children gained a relatively good standard of education.

Their daughter Louisa married Peter Tagg in St. Mary’s Church Dover in 1824, by licence. The bridegroom states he was of St. Olaves of Bermondsey and at that time Peter was still in exile in Calais. So where or how the couple met is not known. Whether Peter risked attending his daughter’s wedding we don’t know but he did give permission for her to marry as she was still only sixteen and therefore a minor. The couple then returned to Tooley Street, Bermondsey. Perhaps this marriage accounts for Peter and Sarah moving to Bermondsey after he received his pardon. Peter Tagg and Louisa had six children; their last was born in April 1834 and sadly a month later Louisa died.

Peter and Sarah’s son, Peter, born on Guernsey,we were unable to trace.

Also born on Guernsey in 1836 was Mary Ann who, a year after her sister’s death, married Peter Tagg, her brother in law. They married in All Hallows Church, Lombard Street and went on to have six children all born before 1850. So Peter and Sarah would have known and had regular contact with nearly all of their Tagg grandchildren. Peter Tagg died in 1855. Mary Ann was to remain a widow making her living as a ‘needle woman’. She died in 1893.

Lastly was Susannah who was born in Calais in 1819. She married a Draper named Peter Charles Kitchener in 1842 in All Hallows Church, Lombard Street. Peter, her father, describes himself on her marriage certificate as a ‘Gentleman’!

Life for Susannah was not to be a settled one. By 1846 her husband was in Millbank Gaol for stealing from his employer;12 shawls, worth 10l. 15s.; 52 yards of silk, 7l.; 2 scarfs, 1l.; 1 pair of cuffs, 3s.; 2 handkerchiefs, 1s. 6d.; 2 1/2 yards of cambric, 1l.; and 6 pairs of stockings, 18s.

He pleaded guilty and was transported to New South Wales for seven years.

We don’t know if Susannah supported her husband as her mother, Sarah, had done for her father almost forty years before. Perhaps it was a blessing or maybe a sadness that they did not have children to consider. It must, though, have brought back some terrible memories for Peter and Sarah.

Peter Charles Kitchener never returned, he died in Inverell New South Wales in 1874.

Susannah, like her brothers, must also have been well educated as she then supported herself as a Teacher of Music and French and later, in 1881, while living with her sister in law, Caroline Kitchener, as a Daily Governess. After this there are no definitive records for her.