Follow us on Facebook @FHofDW

Peter Charles Weston

AKA Charles Peter Weston

AKA Charles Shiffnier

The Mill House, Heathfield, Sussex

10 Quarry Street, Guildford

Wittersham, Kent

Wrotham, Kent

Sevenoaks, Kent

5 North Street, Deal

84 Middle Street, Deal

Occupation: Grocer & Draper

We came across a shocking incident that took place in a house in Middle Street, Deal, on 24th May 1875. The headline that aroused our interest was titled ‘ Attempted Murder and Suicide at Deal’. The facts were given to the Inquest which was held at Deal Guildhall ( Town Hall ) before the borough coroner George Mercer. In front of a Jury of fifteen men, the son, Charles John Weston gave his sworn evidence. The coroner opened the proceedings with the comment that he had never during his experience as a coroner had such a horrible case brought before him. There is some irony in this statement as later in the century George Mercer is to commit suicide by shooting himself ( see James Barber Edwards).

We learn there were six children in the Weston household plus mother Lydia and father, Peter Charles Weston. Peter, we are told, preferred the name Charles and that is how he was known. The eldest son, Charles John Weston, then proceeded to tell the jury what had happened when he awoke during the early hours of 26th May. Charles says he was alarmed by the sounds coming from his parents’ bedroom. Meeting up with his sister, Annie, outside the room, they both tried to gain entry. Charles panicked and ran across the road to the neighbours, Mr and Mrs Clark and their lodger, Robert Bates, to request their help. The lodger found a ladder and Charles climbed up to the window of his parent’s room. Looking in he could see his mother lying, face down, motionless, on the bed. He was unable to see his father. By this time the police, summoned by Robert Bates, had arrived and broken down the door. They removed a crying baby from beside his mother and discovered that Lydia was still alive. Charles was lying, face down, on the carpet by the window. He was naked apart from his shirt which showed, once he was moved on to his back, a large blood stain on the chest. The police found the door had been jammed with a small piece of wood to stop anyone from entering the room. Dr Mason was immediately summoned. The younger children were removed from the house and taken away by Mrs Clark.

Dr Mason turned Lydia over and examined her. There was blood on her face and on the pillow and blood had splattered on the wall behind the bed and the bedside cupboard. As for her husband the police report stated that, ‘the muzzle of the gun was partly under the deceased’s arm’ and that ‘blood appeared to be issuing from his mouth’. A paper of bullets were lying on the table and the bedclothes were all pushed towards the end of the bed as if a struggle had ensued.

The question that the men of the jury must have been asking themselves at this junction of the proceedings was, ‘why?’. The continuing evidence tells us that Charles Snr had not worked since arriving in Deal six years ago, but that he’d informed his family of the recent inheritance of a large sum of money. Charles Jnr had heard it was as much as £200,000, from an uncle in America. His father had set off that day, by train, to advise his bank and deposit his inheritance. The coroner adjourned the inquest to wait for a reply from the bank as to the truth of this matter and to allow Dr Mason to perform an autopsy on the dead man.

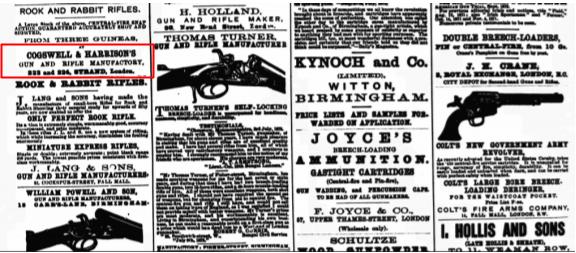

When the inquest resumed a reply from the bank informed the jury that no such undertaking had taken place. It would seem the money was a figment of Charles Weston’s imagination. What was a certainty was the purchase, by Weston, of a black Air Gun and twenty-five bullets from Cogswell and Harrison situated on The Strand in London. An employee remembers his colleague selling the gun to a person of the given description. Strangely Charles gave him a false name, a Mr Hart, 27 North Street, Brighton.

Other witnesses were called including Rev Walter Penfold Brown a Wesleyan minister, who met Charles Snr at Deal Station on the evening of 22nd May, and Josiah Bayly, a retired confectioner of 2 Park Street, Deal who sat in the same carriage on the train as Mr Weston on the Saturday in question. Both of these gentlemen told the jury that Mr Weston was behaving in a very strange way. Mr Emmerson, a solicitor of Sandwich and Deal who, when questioned about dealing with Mr Weston over his alleged inheritance, claimed he and his staff had never met him or even heard of him.

So who was Peter Charles Weston? During the inquest his son told the jury the family had only been living in Deal for six years. What was the story behind this tragic incident? Using information given during the inquest we have researched his life, as far as we were able, and have unearthed an extraordinary, but as yet, incomplete story. There is still much about Peter Charles Weston that remains a mystery.

Peter was born in 1826 in Mayfield, East Sussex, a small rural village populated by a large Weston extended family. From their births Peter and his siblings are singled out from the other Westons with their parents taking them to nearby Heathfield to be baptised, shortly after their births in Mayfield, at the Heathfield Non- Conformist Chapel. Their father John Weston is a Miller and by 1841 he and his wife Ann and their family were living in the Mill House in Heathfield. Using information that arose out of the inquest we have tried to track Peter’s (Charles) journey from Heathfield in 1841 via Guildford, Wittersham, Wrotham, Gravesend, Ide Hill, and finally arriving in Deal in 1869.

In 1851 We think it is Peter who appears on the census using his preferred first name of Charles P Weston in Guildford, Surrey. He gives his birth place as Harting in Sussex not Mayfield. Looking for a Charles P Weston born in Harting, Sussex, has drawn a blank so it seems as though he gave false information. He is lodging with John and Elizabeth Pannell. John is a Grocer and Charles Peter is learning the trade as his assistant. We can find no connection between Charles and the Pannells so can only assume Charles Peter felt the need to escape from his family and the area he was raised in.

By 1857 he married Lydia Highwood in Wittersham, Kent and this is where things become a little complicated. On the marriage certificate Charles Peter gives his surname as Shiffnier identifying his father as Henry Shiffnier a Miller. After extensive research we cannot find this Henry Shiffnier. There is a Sir Henry Shiffner, Rear Admiral Royal Navy, living close to where Charles was born, in Combe House, Hamsey, Sussex. He died in 1859 but he certainly wasn’t a Miller. When Lydia gave birth to their first child, Charles John, in 1859, he was registered as Shiffnier but by 1861 both he and Charles Peter were using the surname Weston. A mystery we cannot unravel.

We were able to track the family to the Sevenoaks area by 1868 as this is where William Henry is born and Charles Jnr tells the inquest that his father was formerly a Grocer and Draper at Wrotham, Gravesend and Ide Hill but we are mystified as to why they chose to make their home in Deal. The son also says, as part of his evidence, that his father hasn’t worked for the last six years so how did he support his family during that time? Charles offers up the places he knows his father has stored money and tells the Jury there were monies amounting to £63 deposited over three Post Office savings accounts, two in Sevenoaks and one in Deal. On the morning of the incident the police are instructed by Charles to look in the chamber pot under the bed where they discovered 14 sovereigns and £20 in notes. This was given to Charles along with his father’s watch which was discovered under his pillow. Charles suggests to the court that these deposits were made by his father from the takings of his previous Grocer and Draper’s shops of which we can find no trace.

The decision of the Coroner is that Charles Peter Weston tried to shoot his wife and then shot himself whilst the ‘balance of his mind was disturbed’. His death certificate states that at the age of 48 years he died by ‘shooting himself with an Air Gun, whilst in a state of unsound mind. Peter Charles Weston’s story is a sad tale but we are pleased we spent time researching this newspaper report. It was up to the coroner, after considering evidence from the Doctor who examined Charles’ body and performed a Post Mortem, and listening to the witnesses to direct the jury to their verdict. Evidence given said that Charles was always a strange man with others using phrases such as ,’ he appeared more excitable than usual’, ‘I thought his manner was rather strange on that day’, ‘From what I know of the deceased I did not feel astonished when I heard’ and ‘He appeared excited and looked angry.’ From hearing these witness reports during the Inquest it seems the coroner decided Charles had mental health issues which prompted the attempted murder of his wife and subsequently his suicide.

The recording of suicide by a coroner is said to be complicated by two major sources of systematic reporting error. One is concealment by relatives of the deceased and the other the state of mind of the person before death. Coroners differed in how they advised juries to treat the circumstantial evidence in these cases. We were shocked that the inquest was held so soon after his death giving no time for the Police to investigate in greater depth. It seems the witness statements were taken at face value and everyone believed the solicitor, Mr Emmerson, who said he had no knowledge of Mr Weston or his money. The assistant in London who actually sold Weston the Air Gun wasn’t available the day the coroner’s letter arrived, but another assistant, who hadn’t served him positively identified Charles from a written description? The evidence proving that Charles Peter attempted to murder his wife before he shot himself is pure speculation.

The inquest was reported widely in both the local press and across the country. It was interesting to see how the evidence was changed and witnesses misquoted to make the case into more sensational reading, not unlike today! According to one local paper who had sent their own reporter to question the witnesses, Charles Peter had ‘beaten his wife around the head with the butt of the gun’ before he shot himself. There is no evidence to back this up. The son made a point of saying Charles Peter was a ‘ kind husband and a kind father’.

This story cannot end for us until we have stopped submitting theories to each other. It is said at the Inquest that Charles visited both Epsom and Wye in the days before his death, even telling his son he was going to take him with him on his next trip. Epsom is famed for its racecourse and Wye held spectacular meetings during the summer. Was Charles a gambler? Was he in terrible debt? We can find no proof of this theory. The use of a different name at his wedding and the way the family moves around the county may suggest he was trying to get away from someone? We just don’t know but we won’t give up looking!

After this terrible tragedy Lydia recovers from her injuries and is found in 1881 living in Duke Street with her children. William, born 1868, was sent away after his father’s death to the Rev CH Spurgeons Orphanage for fatherless boys in London. The Spurgeons Children’s Charity was founded in 1867 by leading Baptist preacher and writer Charles Haddon Spurgeon. He was England’s best known Baptist preacher. Maybe William found the shocking death of his father too much to cope with and through his father’s connections with the Baptist church was offered a place in this prestigious home? We don’t know the reason why he was sent to live there but can only speculate about the shock he must have felt at the manner of his father’s death. William eventually returns to Deal as a young man and helps to support the family. Lydia died in Duke Street, in March 1890.

Charles Peter was laid to rest in Hamilton Road Cemetery where, although badly damaged and lying flat, his headstone can still be seen today. His wife Lydia, who recovered from her injuries of that fateful night, lived with her family in Duke Street and died in 1890 of ‘Apoplexy’. She was buried with him at the age of 52 years. Their unmarried daughter, Lydia, lies with them in this family grave. The inscription on the round-headed stone reads

‘He healeth the broken in heart and bindeth up their wounds.

Great is our Lord, and great is his power, his understanding is infinite.’

Psalm CXLV11.