I don’t know about you but when I think about WW1 it’s usually with images of the Commonwealth War Graves, of soldiers standing in trenches knee deep in mud and I don’t automatically think about ordinary people fleeing for their lives as their country was invaded or as their towns, cities and villages were destroyed and I certainly didn’t think, or even know, about some of those very people seeking refuge in our town until a chance question about ‘Belgian Refugees in Deal’ was asked. So, not knowing anything about them I decided to do some research.

Initially, I couldn’t find any specific mentions about Belgian Refugees in Deal or Walmer in any books or even online so I started looking for mentions of them in the local newspapers held on fiche in Deal library.

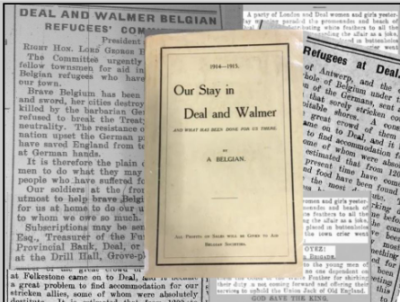

After exhausting that resource I struck lucky with a little booklet called “ 1914-1915 – Our Stay in Deal & Walmer”. This was written anonymously by a Refugee in recognition and praise of Deal and Walmer’s residents and describes some of the things he, and I think it was he and I’ll tell you why later, what he saw and experienced during that year.

This wonderful little booklet, the newspapers and a few documents held in the Kent Archives and some other snippets of information is all that I have been able to find specifically mentioning those refugees that came to Deal and Walmer. I’ve put all that together with some more general sources to tell some of what those refugees and also the townspeople would have experienced during WW1.

The destruction of Louvain IWM-Fleeing Antwerp following the occupation IWM- Leaving Ostend

Almost from the first days of the German invasion, thousands of Belgian fled their country. Up to a million people eventually crossed into Holland, others into France and approximately 250,000 came to Britain. The first refugees to arrive in Britain landed in Folkestone as early as the 8th of August 1914. They came crowded on ferries, small boats and fishing smacks many with only what they could carry. This was to become the largest single influx of immigrants that Britain has ever had and does not include the 150,000 or so Belgian soldiers that also managed to get to here.

Why did they come?

Obviously, the simple answer was the war. As we know Germany on 2 August 1914 handed the Belgium government an ultimatum demanding the right of passage through Belgium for the German armies to attack France, this was declined, German troops none-the-less crossed the border. Britain protested and war was declared.

“The execution of the notables Blégny, 1914” by Evariste Carpentier (1845-1922) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

One witness, who came from the town of Alost, wrote of the 40 people massacred there in September 1914. He mentions the slaughter and butchery of women and children, the robberies, rapes, the bombardment of unfortified towns and the unlawful detention of hostages and, he says, “excesses of all kind”.

There were other reports from other towns and as the scale of these atrocities began to be known the authorities commissioned reports. One of those I found on the ‘Imperial War Museums Collections Online’ pages says-

Alost: “Rue de l’Argent 9 bodies all had bayonet wounds: some with their intestines protruding.”

Neutral Holland

Such reports, some of which later on were even exaggerated for propaganda purposes, would make anyone want to leave. So from the first days of occupation and as the German army advanced, thousands fled across the border into neighbouring neutral Holland, where at its peak an estimated 1 million refugees including Belgian soldiers were cared for in homes and eventually in camps.

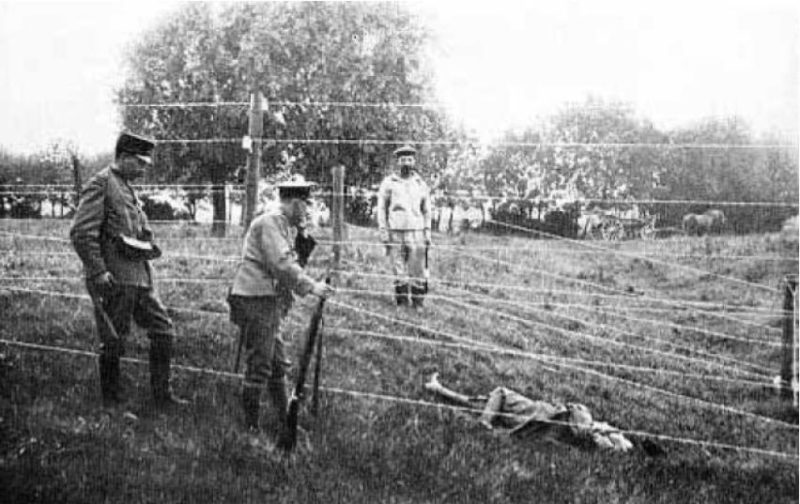

With the Germans starting to make it difficult to cross into Holland and as their armies advanced through Belgium thousands travelled to the north Belgium ports and refugees started crossing to Britain. Others crossed into France. To prevent further crossings into Holland and easy access for spies, the Germans in 1915 erected an electrified fence along the border. They called this the ‘Wire of Death’ and an estimated 2 to 3 thousand people were killed trying to cross through it.

Approximately 6,000 Belgian civilians were massacred during WW1.

Making Plans

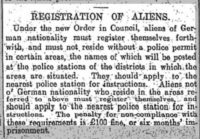

In readiness for war, the UK government had been making plans that would affect everyone including the refugees who would eventually arrive. Once war was declared these plans were pushed through Parliament. Including, on the 5th of August, the ‘Alien Restrictions Bill’. Notices were printed in newspapers and posted on public buildings and although mainly aimed at Germans and Austrians all foreign nationals were required to register. Failure to do so could lead to fines or even a prison sentence. German and Austrian men aged between seventeen and forty-two were interned.

Spy Mania

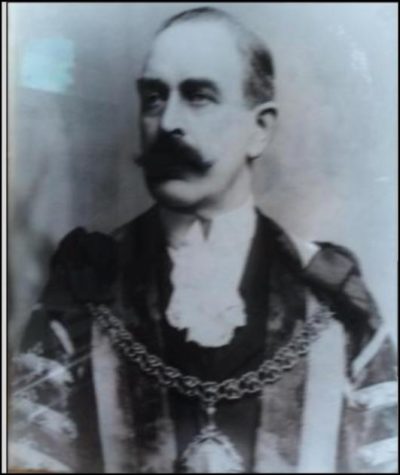

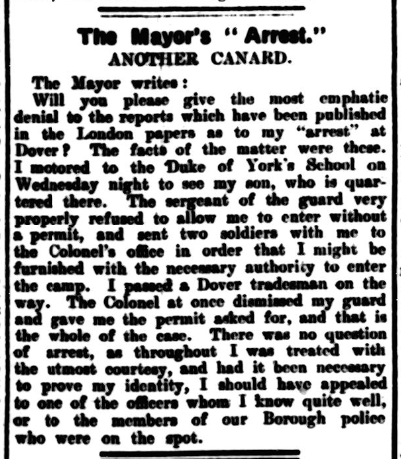

With Dover and Folkestone being the main ports used for military traffic to and from France and also as ports of entry for refugees there was a very real threat of spies posing as refugees or military personnel coming into Britain. Spy mania ensued. Even the Mayor of Deal, Charles Hussey, it was wrongly reported in the press as being arrested as a potential spy while walking on the cliffs. He wrote a letter to the local newspaper to correct this.

Support for the Refugees

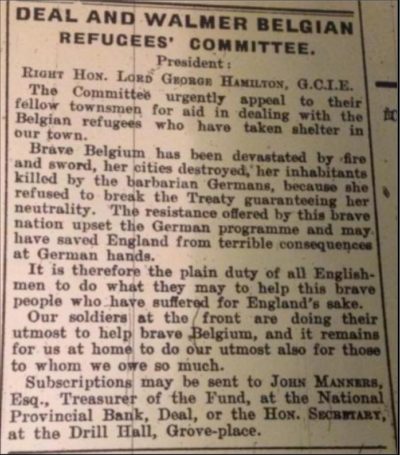

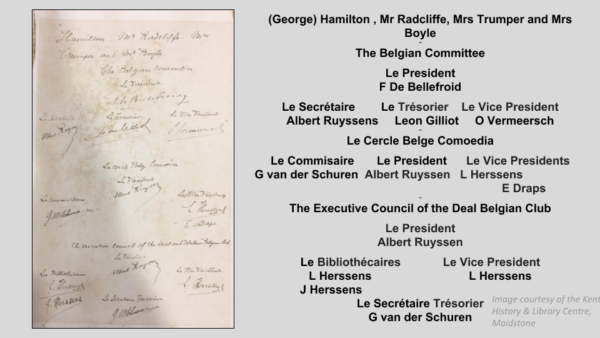

Initially, all action for dealing with the Refugees was taken by privately run bodies. Then on 24 August, the Foreign Office received a letter the ‘Wounded Allies Relief Commission’ suggesting a scheme to treat wounded Belgian or French soldiers in Britain. George Hamilton who at that time was Captain of Deal Castle and a member of the Foreign Office was conferred with.

As he was of the opinion “it would all be over by Christmas” he thought that it was unlikely that the wounded would need to be transported across the channel to be treated. But he did say that with the Germans overrunning Belgium

“…there must be a very large number of refugees who will come to this country almost penniless..”

and that

“… we ought to be prepared to do our best to temporarily support them..”

He suggested the relief commission instead of using their funds to help wounded soldiers they instead use them to support refugees. Whether this happened or not is unknown but it shows there were people in the Foreign Office who were becoming aware of the growing desperate situation.

Brussels Falls

Following the fall of Brussels, the Belgian government moved to the then unoccupied Antwerp. Many of its citizens followed and they were anxious to know if Britain would approve arrangements for receiving those who could not be accommodated in Antwerp.

The Foreign Office contacted the Home Office who decreed the refugees were to be treated as friends and could land provided they did so via the approved ports and once here abide by the Aliens Restrictions Order.

Eventually the Local Government Board, under pressure from Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, would take on the responsibility for the refugees.

The Local Government Board supervised the laws relating to public health,

the relief of the poor, and anything related to local government

It was announced in the House of Commons on the 9 September 1914 that the UK government had offered to the Belgium Government hospitality to the victims of the war.

By the time the government’s request for local assistance arrived in Deal, Mayor Charles Hussey, had already gained first-hand knowledge of the needs of the refugees, not just from George Hamilton but also from Mr & Mrs Bouchier of Deal who had been helping with the arrivals in Folkestone. He began visiting the towns lodging and boarding houses and rentable properties creating a book of available addresses for the purpose of housing refugees.

Antwerp Falls

On the 08 October as Antwerp was being evacuated thousands of refugees arrived in Folkestone. On hearing about this, Charles Hussey, armed with his address book, visited Mrs Penrose-Fitzgerald of the Folkestone Refugees Relief Committee. A decision was made to send several families to Deal although how many initially came is unknown. On Sunday 11 October following the fall of Antwerp and, as the Germans were advancing on Ostend, a phone call was made from Folkestone to Charles Hussey saying “ For God’s sake come & help us; we are overwhelmed”. Accompanied by Mr and Mrs Bouchier he went to see what could be done.

The Alost witness mentions his own flight to Ostend. When he and the 30,000 inhabitants of the town were evacuated before its eventual capture at the end of September.

He says how they left with all they could carry and that in nearby villages trains awaited to take them on to places such as Ghent, Brugge and Ostend. Then in October, as Ostend was threatened, they had to take flight again. He was lucky enough to secure a passage on an overcrowded steamer to Folkestone on which he says they had “…an ideal crossing on a sunny day with bright blue skies so people sat on deck and others joined nuns in prayer ”.

On arriving in Folkestone he says they were met by Mrs Penrose-Fitzgerald and her fellow volunteers.

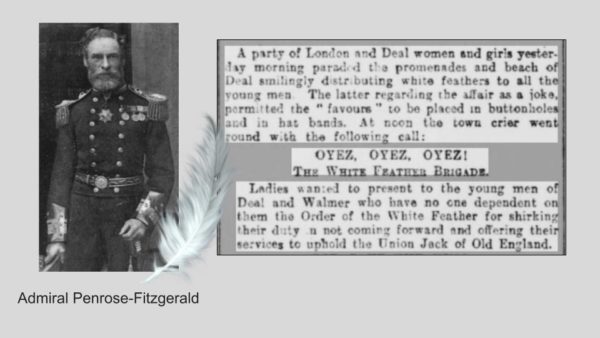

Interesting her husband was the person who started the white feather campaign by organising a group of thirty women in Folkestone to distribute them to men -not in uniform and this soon caught on even in Deal where it was reported that “…A party of London and Deal women and girls– paraded on the promenade of Deal distributing white feathers to all the young men not in uniform”…

Even the town crier got involved requesting the help of the town ’s young ladies to do do this. The government soon responded though by issuing badges which could be worn by civilians occupied in war work.

Refugees Arrive in Deal

At the time Charles Hussey received the call for help nothing was ready in Deal for a sudden influx of refugees and their immediate needs. Before their arrival, a building of sufficient size was quickly looked for and the Drill Hall in Hope Road was decided upon.

Our Alost witness says that they travelled to Deal by train and were then met at the station by Mrs Hussey and several other ladies who took them to the Drill Hall. On arrival at the hall, he says Mayor Hussey and the ladies worked tirelessly to provide whatever assistance that they could. Many of them did not know what would happen next. He says he spent his first night in the Drill Hall with the other refugees and the next day he saw Mrs Hussey and her fellow volunteers allocating and finding places for them all to stay.

An extract from 1914-1915 Our Stay in Deal & Walmer tells that

“… some poor people living in Mill Road and other localities received into their homes strangers as their guests, sharing with them the fruits of their daily toil- proof of the admirable fellowship existing among the poor whose modest sacrifices are often ignored….”

Those that could afford to pay were found apartments, houses or rooms in lodging houses. The Town’s Corporation had purchased several houses including Royston House, allowed these to be used to house Belgian Refugees before they moved on. The houses were then used by Scottish troops and Orient House was used as a club for the wounded soldiers from the various hospitals in the town. Those who could not be often placed in local people’s homes for which the Committee’s fundraising eventually paid for.

Over the next weeks, hundreds of refugees were to arrive all needing food, clothing, care and accommodation.

The trustees of Wesley Hall and the Congregational Church, of Deal, also gave over their premises as dormitories and meeting places to those who were to arrive over the coming weeks.

Townspeople helped by providing bedding, food and clothing. Alderman Edgar even sent a hundredweight of bones from which to make soup.

Alderman James Edgar owned the meat packing factory in Deal that eventually went on to pack the Government Maconochie rations.

After food and a place to stay, money would have been the next concern, and for those that did have it, Mayor Hussey assisted with its exchange. He also helped the refugees to register with the Police in accordance with the Aliens Restriction Order. A Sergeant Ashby even attended the Drill Hall itself to assist with this.

It was not until 21 October that the Deal & Walmer Refugee Relief Committee was formed to take over the official provision of food, lodging and care of the refugees.

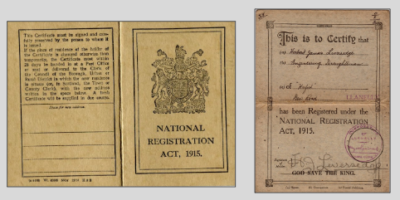

At the end of 1914 a central register was in place and all refugees, over sixteen years of age, received and had to carry a certificate of registration.

Restrictions

On the 21 October, the Home Office announced it was “inadvisable to send Belgian Refugees to the eastern and Southeastern coastal towns”. Luckily for our refugees, and others in the now restricted areas, it was decided they could stay if they had already gained permission to do so from the local police.

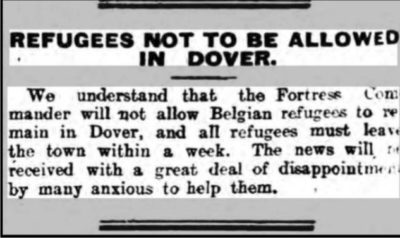

On the 23 October General Crampton, Fortress Commander of Dover issued an order which was publicised in the Dover Express stating that all foreigners should be excluded from Dover.

Appeals for Help

At the end of October 1914, an appeal was placed in the local paper. There were many other such appeals, followed by fundraising activities most of which were reported on in the newspaper. Recognising the town couldn’t be expected to raise all the funds necessary to care for the refugees Mayor Hussey made an application to the Local Government Board for financial assistance. This really was needed as an eventual twelve to fifteen hundred refugees were eventually fed, housed and cared for in Deal and Walmer.

The curate of St.Thomas’ church in Deal, the Reverend Father Anthony Limpens and a fellow Belgian, also sprang into action. Since the arrival of the Belgians, who were mainly Catholic, he undertook to read out from the pulpit after each service the names of those for whom letters had reached the town but whose addresses were not known to the writers.

He gave over his home as a storeroom for donated items of clothing which he then distributed to those in need. He also gathered a large quantity of wool and gave it the Belgian women who wanted to knit items for the troops fighting in Flanders. A Mrs Hills of Deal suggested a weekly working party to produce ‘much-needed comforts’ for soldiers and refugees alike, as well as items of embroidery and needlework. She opened up her home to a group of 20 or so Belgian ladies to meet, take tea and talk while producing these necessities. An exhibition and sale of their work took place in Deals Masonic Hall which earned itself a write up in the local newspaper including, on this occasion, the names of some of the Belgian ladies themselves.

Belgian Ladies Patriotic Work Exhibition at The Masonic Hall.

“Some very beautiful examples of artistic needlework …were on view at the Masonic Hall on Wednesday 19th May 1915………………… Among the stall holders were ………

Mesdammes Herssens, Ruyssen, Dupont, Versmeerch, Mdlles. Jaquemain, Van Uxem, Vandershuren, and little Mdlle. Versmeerch.”

Belgium

The Belgian men also gathered together at Mangilli’s Restaurant, which was on the site of present-day Dunkerly’s restaurant, to form a local branch of the Franco-Belge Committee. This international committee was first formed in October 1914 in London to give information, advice, recommend fellow refugees to other societies and committees and also to try and find them employment and here in Deal it was no different.

Whilst here the refugees took a close interest in what was happening in their homeland mainly through the exiled Belgian press. The’Moniteur Belge’ was the official Belgian government newspaper during WW1. It may have been in this newspaper that our refugees read about the decree, made on 15 January 1915 by Moritz von Bissing the Governor General of occupied Belgium. This imposed a tax on the Belgian people at six times the rate of 1914. Where ever they heard about it they decided to write a letter to the Belgian Minister of Foreign Affairs, protesting against this tax. This was sent to the exiled government in Le Harve and suggested they appeal to the neutral countries “to intervene to end this violation”. They also protested about the extra ten percent penalty that was to be imposed on those that had fled Belgium if they did not return before 01 March 1915. The extra ten percent tax was mainly aimed at those who had fled to Holland in an attempt to get the much-needed workforce to return.

One refugee family who came to Deal did return to Alost. Who they were or if their return was due to the decree is unknown but on arrival, they found their home was occupied by a German officer who was using their drawing room to pass judgements on ‘guilty’ Belgians.

Belgian Refugees Entertain

The founding of the Deal Cercle Belge Comoedia was also down to the Franco Belgee members. The Cercle put on concerts in aid of the refugees and to raise funds for the future needs of the widows and orphans of fallen Belgian soldiers.

A deputation from the newly formed Cercle visited the Consul General of Belgium in London to announce its inauguration he in return “..wished them good luck and success in their efforts and a rich harvest of profits for the good cause.”

The first Cercle Comoedia concert was held on 30 December 1914 at Stanhope Hall, now the Astor Theatre. As well as their own performances they were able to secure celebrities of the time such as the Lyric Theatre’s Roland Cunningham.

Desperately trying to leave occupied Belgium

Throughout 1914 and 1915 people still tried to leave the occupied areas and some tragic cases were reported on in the papers –including one of a suicide on board a Dutch steamer, who was sheltering in the Downs on which a woman“….seeing no way forward had hung herself in her cabin” She was from Liege where her house had been reduced to ruins and her husband and only son had been killed

Then in November, another desperate case was reported on luckily this time with a happier outcome. Titled “ The Pitiable Plight of Two Families’ and in brief, it said

‘On Wednesday 25th November 1914 a small group of 3 women and 10 children were landed on Deal Pier. They had crossed the channel during a gale in 3 Ostend open fishing boats. First, they had tried to land in France then they attempted to land at Dover but were refused permission due to the regulations there, but Mr. Fisher a Trinity Pilot was put on-board with instructions to take them to ‘some other English port’. With the wind failing in the Downs he anchored off Deal Pier it was then decided that they should land. The Coastguard was alerted and after Mr.Geddes the Customs House officer had completed the necessary formalities– word was sent to Wesley Hall to make preparations for these poor women and children. Dr. Mason the Port Medical officer was summoned to examine the party who had suffered greatly from seasickness and exposure. Once at Wesley Hall though, it was reported that they soon recovered after receiving warm food, dry clothing and a bed.’

‘On Wednesday 25th November 1914 a small group of 3 women and 10 children were landed on Deal Pier. They had crossed the channel during a gale in 3 Ostend open fishing boats. First, they had tried to land in France then they attempted to land at Dover but were refused permission due to the regulations there, but Mr. Fisher a Trinity Pilot was put on-board with instructions to take them to ‘some other English port’. With the wind failing in the Downs he anchored off Deal Pier it was then decided that they should land. The Coastguard was alerted and after Mr.Geddes the Customs House officer had completed the necessary formalities– word was sent to Wesley Hall to make preparations for these poor women and children. Dr. Mason the Port Medical officer was summoned to examine the party who had suffered greatly from seasickness and exposure. Once at Wesley Hall though, it was reported that they soon recovered after receiving warm food, dry clothing and a bed.’

St. Nicholas Celebrations

With Christmas soon to be upon the town a young girl from Deal, who had been at school in Ghent, pointed out the importance of St. Nicholas to the Belgian children to one of the Committees. They decided to organise a ‘St. Nicholas fete’ at Stanhope Hall.

With Christmas soon to be upon the town a young girl from Deal, who had been at school in Ghent, pointed out the importance of St. Nicholas to the Belgian children to one of the Committees. They decided to organise a ‘St. Nicholas fete’ at Stanhope Hall.

Invitation cards were sent out saying in French saying

“Saint Nicholas invites all his Belgian friends to his party Saturday, December 5th at 3 O’clock Stanhope Hall

(near post office) Deal.”

On that Saturday of Sinterklaas Eve a party for the Belgian children, their parents, some local children and the wounded Belgian soldiers from Deal, Walmer and the surrounding villages, was held. It was reported that

“A 12 foot Christmas tree was lent by Messrs. G and A Clark, Ltd of Walmer. Tea was served, games played and then with lights dimmed St. Nicholas appeared with a sack full of ‘crackers, sweets and presents’. At the end of the evening, the Belgium National Anthem and God Save the King was sung before the gathering came to a happy ending”.

Government Reports

In November 1914, as the government started to get to grips with the refugee situation, requests for information from the towns hosting the refugees were made. At the Kent Archives, there are the replies of the District Relief Sub-committees which give the number of refugees in each to town and village.

A report in the newspaper stated that by the end of 1915 there were 163 refugees living in Deal & Walmer. I know that there does seem to be discrepancies in numbers here particularly after the twelve to fifteen hundred that had initially been reported. However, many of the refugees who came to Deal and Walmer moved on. Some went to be with family members in other parts of the country and they were helped on their way by the local committees. If they needed or wanted employment they were moved to where it was found for them and, of course, the young men may have gone into the Belgian Military. As the Home Office had stated that it was “..inadvisable to send aliens to the coastal towns..” those that could go elsewhere were probably encouraged and helped to do so. Local committee membersMrs Bouchier, Mrs Davis and Mrs Hughes wrote to committees all over the British isles endeavouring to find homes for some of the “professional classes”.They were successful in finding homes for 180 families.In May 1915 the Deal & Walmer Refugee Relief Committee presented its accounts which were then printed in the paper. This showed that they paid for clothing, rents, rail fares, gave grants to those in need. The total amount spent by that time was just over £344. The fund was wound up in May 1919 which suggests that most of the Deal and Walmer refugees had returned home by then.

Wounded Belgian Soldiers

Here in Deal & Walmer several hospitals were set up for the care and recuperation of soldiers and our Alost witness stumbled upon the Grange hospital whilst out walking. He describes how he saw the Red Cross flag floating over the hospital and he says “wafting through the air a well-known song sung by male voices reached my ears and My heartstrings thrilled at the sound of this familiar melody”. And that he then “.. knocked at the door to ask if this was indeed a hospital for Belgian soldiers and if so could he be allowed to look around?”

He gave praise and thanks to the staff of the hospital particularly to a Mrs.Trumper who told him that “….we must amuse our invalids”.

The Patriots League

Mrs Trumper was very active not only with the care of wounded Soldiers but also the refugees and was the President of the towns Patriots League, a national organisation providing for the refugees, whose president was Princess Mary.

In Deal & Walmer The Patriots League helped support thirteen families with food, clothing, wood and coal. These resources were paid for by the weekly donations of a penny or more from its members and other much larger donations. It is said the school children of Deal, Walmer and Kingsdown also contributed their pocket money to the general fund.

The Patriots League planned and put on a Cafe Chantant (cabaret style fete) at Walmer Parish Hall on May 6th 1915. Performances were given and stalls were run by the town’s people and the Belgians themselves. During tea, the Royal Marines string band played a selection of waltzes and the tea was served by waitresses wearing sashes in the Belgian colours. A telegram from Princess Mary conveying her thanks to the Patriots League was also read out.

“The Princess Mary Desires to convey her sincere thanks to the 537 members of the Young Patriots’ League for their kind greeting which her Royal Highness much appreciates” (Buckingham Palace 12.20)

Mrs Marke Wood, who with her daughter later gave us the park in that name, declared in her speech that she would be

“… very pleased to assist in paying the rents of Belgian refugees in need ….” this obviously relieved a large financial burden on the fundraising committees and may explain why there were very few reports of fundraising activities in the newspapers after 1915.

The Belgian Club

The Patriots League also had a hand in establishing The Belgian Club. They approached Mr. Chitty, owner of Citizens Hall, to see if it could be used by the Belgians to meet and feel more at home amongst themselves rather than in strangers homes or cafes.This was to become a much-appreciated club and library from which they continued to arrange their own fetes and concerts in aid of those Belgians in need. The club was opened by Mayor Redsull who remained as Mayor throughout the rest of the war.

Education

As not many Belgian adults could speak English lessons were provided by those locals who could speak French. Likewise, there were offers from Belgians themselves to teach French. Oddly in the local sources, there is only French and not Flemish mentioned. Flemish being the language of north Belgium which is where most of our refugees came from.

Most of the Belgian refugees in Deal & Walmer came from these areas– Ostend (Osstende), Bruge, Antwerp, Alost (Aalst), Brussels and Ghent (Gent)

However, French was the language of the government and legal system and as the majority of the refugees staying here were of those professional classes, most would have been bilingual.

The children also needed to continue their own education and about 50 were received at the St. Ethelburga’s Convent. Here they were taught in a similar way as they had been in Belgium. Some of the more-able English speaking boys were admitted to a school in Deal.

Air Raids on Deal

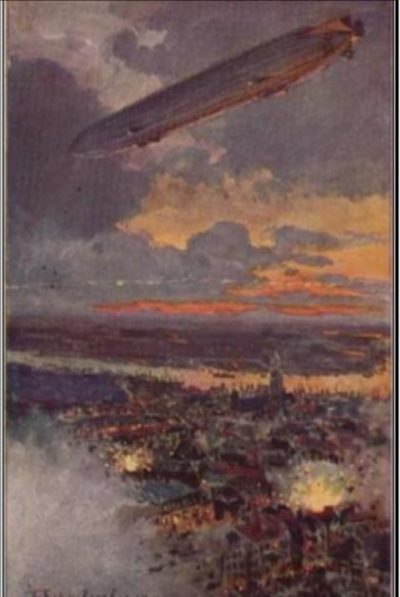

WW1 saw the beginnings of air warfare which brought Zeppelin raids as well as those by aeroplane. The Deal area suffered 37 raids throughout the war. One newspaper report described how in the early hours of 17 May 1915 a Zeppelin passed over Deal and Walmer. The first the town knew of this was when there were some loud explosions that shook the windows in an ‘alarming manner’. People hastily dressed and rushed to the seafront where they saw ‘the huge monster pass over the town” and nothing was heard again until bombs were dropped on grazing land at Oxney.

Restriction, Registration and Conscription

Throughout the war, there were amendments to and reminders about the Aliens Restrictions Act. These were printed in the newspapers and were particularly aimed at the Belgians who perhaps, as ‘friendly aliens’, sometimes thought that the regulations really didn’t apply to them. These reminders came with the warnings that failure to comply could result in fines or imprisonment.

Throughout the war, there were amendments to and reminders about the Aliens Restrictions Act. These were printed in the newspapers and were particularly aimed at the Belgians who perhaps, as ‘friendly aliens’, sometimes thought that the regulations really didn’t apply to them. These reminders came with the warnings that failure to comply could result in fines or imprisonment.

Then on August 15th 1915 everyone across Britain, no matter the nationality, aged between 15 and 65 and not already serving in the army or navy, had to register. Everyone was then issued with and had to carry a National Registration Certificate.

Then in 1916 came conscription not just for British men aged between 18 and 41 but for all Belgian men aged between 16 & 40. The previous year in May 1915 had already seen the conscription for unmarried Belgian men aged between 18 & 25.

Now obviously anything official was placed in the papers but I haven’t found any local press with translations into French or Flemish announcing conscription for the Belgian men. Locally the refugee committees would, of course, have kept everyone informed of all official notices and I assume that like our conscripted men the Belgian men also received conscription notices through the post.

Birth, Marriage and Death

Life goes on wherever you are and so there were babies born, couples married and people sadly died.

Births

Between November 1914 and May 1916, eight refugee babies were baptised. The first was on 18 November 1914 and poor Rosalie, the mother of George here, must have been heavily pregnant when she fled her home.

18 November 1914

George Albert Ignatius LOTAIRE

son of Alphonse & Rosalie nee MEULEMEESTER

Mill Hill (Belgian Refugee)

Marriages

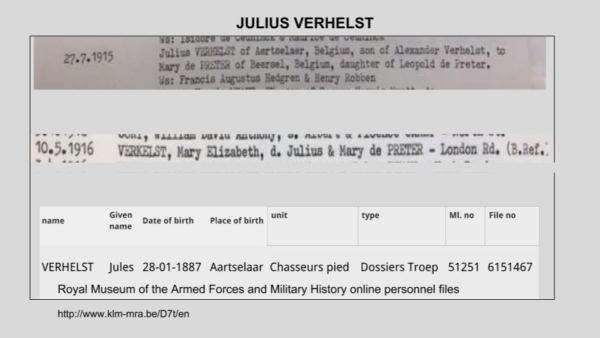

Four marriages took place between November 1915 and November 1918 one of which was between Julius Verhelst and Mary de Preter. This took place on the 27 July 1915 and was followed by the baptism of a daughter, Mary Elizabeth the following May. And at that time they were living in London Road. Julius can be found in the Belgian military records so he may well have already been in the army at this time.

Burials

There were four burials recorded between March 1915 and November 1918.

Some Belgian Refugees of Deal and Walmer

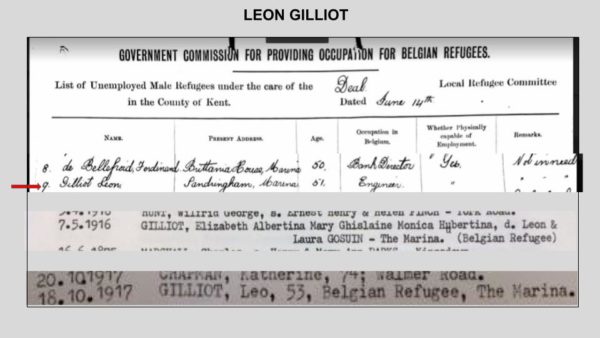

Leon Gilliot

On the list for unemployed in June 1915 a Leon Gilliot appears living in a property called Sandringham, on The Marina. He was an engineer by trade and was the Mayor of Aertselaer when the Germans invaded. He and his wife Laure arrived in Deal with their seven children and their eighth, Elizabeth, was born and baptised here in May 1916. Leon died in 1917 aged 54 and was buried in October in Hamilton Road Cemetery. After the war his wife and children, like nearly all those refugees who came to safety in Britain, returned home to Belgium to rebuild their lives. Leon was later disinterred and taken home in 1919.

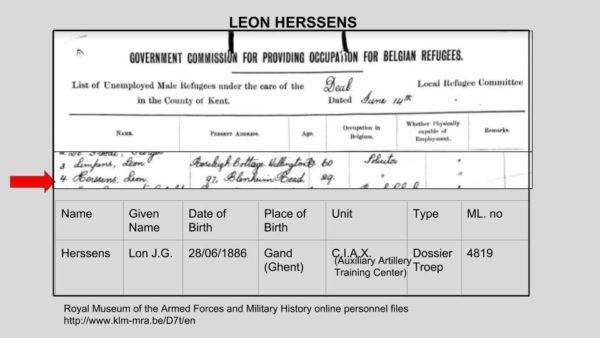

Leon Herssens

Leon Herssens appears on the list for the unemployed as a 29-year-old solicitor living in Deal at 97 Blenheim Road. At some point, after July 1915 he joined the Belgian military. He is mentioned in the newspapers and frequently gave speeches and performances and is listed as vice president of both the Cercle Belge Comoedia, of which he was a founding member, and the manager of the Belgian club as well as being joint librarian there with his wife.

Limpens family

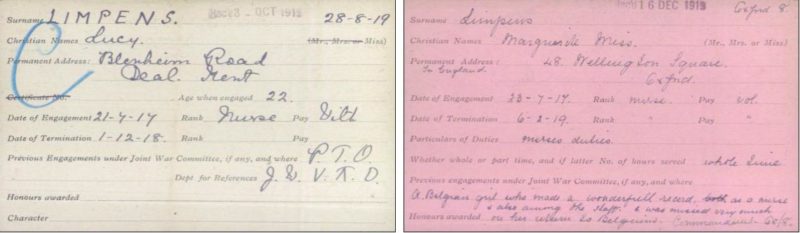

Leon’s wife was Jeanne Limpens and the niece of Father Limpens, curate of St. Thomas’, Deal. Her father Leon, mother Leonie, and 3 sisters were also here and lived in Wellington Road. They all moved to Rye in May 1916 and it is from there that they returned home to Alost after the war. Another uncle, Emile Limpens, was here with his wife and two daughters living in Blenheim Road. The daughters, Lucy and Marguerite, both joined the Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment in July 1917. They both went on to serve in a Military Hospital in Oxford before their return to Belgium sometime after December 1918. Sadly, their father Emile died in the home of his brother, Father Anthony Limpens, on the in November 1918. He, like Leon Gilliot, was buried in Hamilton Road cemetery and in 1919 disinterred and returned home.

Belgian Independence Day 1915

The 21 July 1915 was the 85th anniversary of Belgian independence which was celebrated in the town with a mass at St. Thomas’ and Belgian flags were flown on many of the buildings of the town including the Town Hall.

A reception was held at Stanhope Hall where Leon Herssens gave a report of the Belgian’s time in Deal and Walmer. He also gave a speech in French that ended with a short address which was translated into English and I have found a copy of that at the Kent Archives which reads …..

In the name of all the Belgians in Deal and Walmer, assembled today with their English friends to celebrate, in exile, the anniversary of their national Independence, so contemptuously trampled upon by the Germans in 1914.

Thank with all their hearts the inhabitants of this country of refuge England- and especially all the inhabitants of Deal and Walmer for their generous, devoted and continued Hospitality.

There were at least two pages of signatures of both the Deal & Walmer and the Belgian committees but only one page survives.

Sadly the original copy of the speech is missing but it is in full, in French in the Booklet ‘1914-1915 Our Stay in Deal & Walmer’ and in the local newspaper of the time.

One sentence does stand out “ We await with patience the hour of our deliverance”. They waited another three years for the war to end and for some four years to return home.

Very little is recorded about the Refugees after 1915 this is probably due to the fact that most of those who originally came had moved on and those who stayed were able to support themselves and since Mrs Marke Wood was now paying the rents of those refugees in need the financial burden on the committees was greatly reduced.

Returning to Belgium

From early on in the war the refugee committees, all over the country, had been setting funds aside to assist with the return of the refugees once the war was over. However, there are no surviving records for the refugees return home from Deal and Walmer.

Leon Herssens did return to Alost taking up his position as a solicitor at the same firm that he and his father-in-law had worked at before the war. He remained there until his death on the 13 January 1931.

I don’t know what reception any of our refugees received on their return home. Some, though, were not looked upon favourably by those that had stayed and suffered under the occupation not just with the heavy taxation but also the forced labour, starvation, deportation and the harsh treatment we now associate with WW2.

And Today

There is very little left to mark the refugees time here in Britain, except maybe a plaque in some towns. Folkestone has ‘The Landing of the Belgian Refugees’ painting and on The Embankment in London, there is a monument.

Here in Deal there are only the newspaper archives and the booklet.