Follow us on Facebook @FHofDW

The Deal and Walmer Institute

Before the 1860s, Deal and Walmer, like a lot of other towns, had introduced a ‘Mutual Improvement Society’. This movement began in London at the end of the Napoleonic wars and slowly spread throughout the country. These societies were of the people not for the people. They were democratic and usually provided instruction to others by working men. Charles Dickens was a great supporter of these institutions and the education of working class men. He promoted ‘Free Itinerating Libraries’. These were boxes of ‘excellent’ books carried around the country and borrowed by the lower classes in various towns and cities. The Mobile Library vans of their day, which were so popular in this country but now, sadly, seem to have all but disappeared. This objective of the pursuit of knowledge and self-taught men was popular all over the country.

Here in Deal we embraced this movement. In fact we were already running a similar society between the years of 1840 and 1850. Wealthier local residents made donations towards the purchase of books that would be circulated amongst members. There may have been a few copies of worthy novels in that collection but most were books and papers on travel, science, mathematics and politics. The latest reading material would be discussed as a group. These meetings were originally held in a room in The Royal Adelaide Baths built in 1835. This idea grew in popularity within the town and by 1851 Deal had established its ‘Deal Mutual Improvement Society.’ By 1858 Mr Edward Hayward, the founder of the Deal, Walmer and Sandwich Telegram newspaper, was running a ‘Sol-fa’ class (the Curwen hand/rhythm signs developed to help children and adults learn to sing) which attracted over 100 people and met twice a week at the Congregational School Room in Lower Street and eventually moving to the Town Hall. Here, as reported in the local paper, the numbers of people attending meetings and lectures continued to grow and at one lecture the paper reported that, ’the large crowd became increasingly uncomfortable.’ It was obvious that a larger meeting and performance space was required and by the early 1860’s a committee of local residents worked extremely hard to make that dream come true.

It was decided by the supporters of this very successful Mutual Improvement Society, with the generous donation of some ground by Captain Betts, to sign up to a scheme initiated by Midland and Birmingham Bank, which allowed local people to borrow money to provide buildings for gatherings. Named ‘The Deal and Walmer Public Rooms Company’ it enabled the committee to build suitable rooms on the land supplied. Many of these companies were set up by local people across the country.

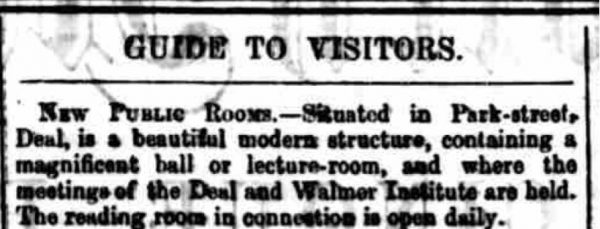

The Deal and Walmer Institute was built on a commodious site in Park Street, roughly where the overflow Aldi car park is today, in 1864 at the cost of £3,000.

It contained an assembly room which seated up to 800 persons, plus a committee, Billiards and reading rooms, and a library. The building was owned by The Deal & Walmer Public Rooms Company Ltd. The purpose of the company was to provide a large space for the townspeople to gather in their local area and participate in a variety of exhibitions, cultural pursuits including the provision of Billiard tables, a very popular activity at the time. As far as we can tell this local company maintained control of the buildings they either built or purchased. In some areas of the country, where others of these companies were established, they were responsible for backing Music Halls and other larger venues.

The Deal and Walmer Institute opened its doors in 1864.

The day-to-day running of the building was the responsibility of a committee made up of local people. Their role was to select entertainment that would be welcomed by the townspeople and sell lots of tickets. Ticket sales were their main source of revenue to enable them to pay the agreed rent to the Company.

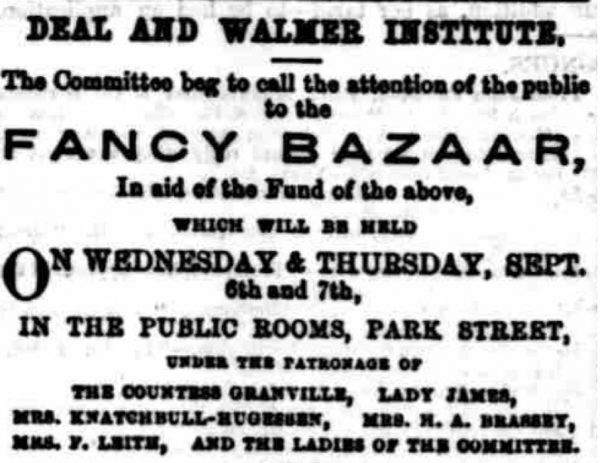

So what events were available and attracted large audiences? Apart from Billiards, which was very popular and brought in a steady income, publicity tells us there was the enjoyment of a ‘Fancy Bazaar’ and a ‘Loan Art Exhibition’ which included ‘Curiosities and Works of Art’ kindly lent by the Directors of the South Kensington Museum, later to be renamed The Victoria and Albert Museum.

If you were interested in purchasing a property in the town, Sale Auctions were frequently held in the large Assembly room.

On Monday September 11th 1876 there was a ‘Grand Dramatic Performance’ by the standard French Opera Company with ‘Full Costumes and Grand Effects’. If you wished to reserve a numbered seat in the Stalls, it would cost you 4 shillings. Unreserved seats 2 shillings. Third seats 1 shilling. This event was hosted by Giraud’s Marine Library, Beach Street; where you could purchase your tickets and see a seating plan. Just like the West End!

The Park Street Rooms also hosted the annual Deal and Walmer Flower Show. Not only could you drift through the rooms admiring the displays of flowers, fruit, and vegetables but a Mr Doorne provided music on the pianoforte during the exhibition. An event the ladies who created this website would most definitely have attended!

A ‘Grand Evening Concert’ by the English Glee Union would have been a real treat for some with the talents of Madam Ashton, Mr Colson Phillips and, the unusually named, Mr Fountain Mead (who also played the piano) on display. This Madrigal Union had found much favour and success throughout the country and played to packed audiences.

The Institute produced a monthly journal, a copy of one of the first publications – the July 1865 edition – is held in the archives of Deal Museum. Amongst the entertainments listed for this month is the notice of a very popular event throughout the country, ‘Penny Readings’ (so called because the entrance to these events cost just a penny!)

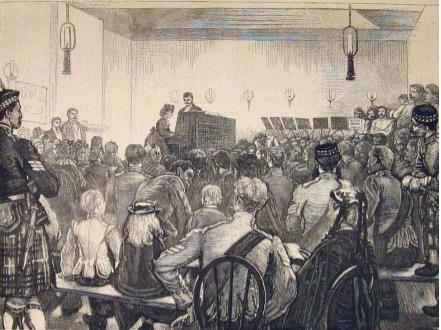

Some of the events advertised did not attract the crowds the Institute Committee had hoped for. Dr T. S. Rowe of Margate was booked to give a lecture on ‘Instinct in Animals’ but very few people attended. A week later, however, the Committee was delighted that the Penny Readings, ‘drew together one of the largest and most fashionable audiences we have had the pleasure of witnessing.’ They note there was frequent applause and hearty encores for the performers. In December 1866, the Penny Readings again attracted an ‘immense audience’ that flocked to the Institute’s Assembly Rooms. So great was the crowd that many of them were turned away, disappointed. One of these disappointed customers, a lady, complained the space was taken up with the great array of crinolines worn by the lucky females who did find a seat!

Every available inch of ground was occupied with some customers having to stand all evening in very cramped conditions. Why was this particular entertainment so popular with the public? We decided more investigation was necessary!

Whereas the ‘Catch Clubs’ of earlier in the century had already developed this idea of sharing music, songs and sometimes poetry, it was not an entertainment. They performed only to other members, often writing and rehearsing something special for the evening. They often met in a room above a Public House.

The Walmer Catch Club met at the Royal Standard on the Dover Road. No ladies were involved apart from the occasional, by invitation only, soprano. According to our research it was very much a male environment and could involve a lot of claret and tobacco into the early hours! The Catch Club was not suitable for a wider audience. The local population required something more on the lines of entertainment and a performance that they could be part of, and the Institute and its Penny Readings filled that gap.

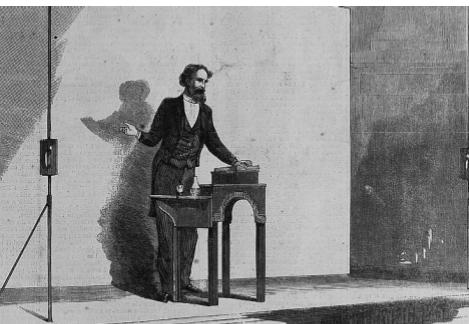

It seems almost certain Mr Charles Dickens was responsible for the phenomenon of Penny Readings. The Victorians adored the writings of Mr Dickens. The characters, the language he used, and the Victorian ethics contained in the stories shined through, and Dickens became the celebratory of his day. So famous, in fact, that when Dickens gave readings of his books people flocked to both see and hear this marvellous author reading passages from his novels.

In 1857 he gave his first ever reading of a Christmas Carol in London and an audience of 2,000 devoted admirers packed the venue!

Dickens had the advantage of being a talented actor as well as an author and was able to bring the well-loved characters from his novels to life in front of his audiences. He travelled light as he made his way around the country. Charles had no need to rely on backdrops, costumes or set dressings. He brought with him two pieces of cloth which hung behind him and lit from above with a gas lamp. Standing behind a simply made lecture table he enthralled his huge audiences by reading passages and taking on the characters voices from his books.

The people who got to attend these magnificent performances were the lucky ones. They certainly paid more than a penny for their place in the venue. We have no evidence of Dickens reproducing any of his reading performances in Deal but there were many culture hungry citizens in our town and in other areas of the country who both read about these exciting events in the newspapers and heard, through word of mouth, how entertaining they were. The people were eager to experience something similar. This type of event spread rapidly throughout the country and, it would seem, became very popular in Deal and Walmer too.

The evening was open to anyone in Deal and Walmer who thought of themselves as a bit of a thespian and were bold enough to stand up in front of hundreds of people. The entertainment was not about listening to professional actors or reading from books.

Each performer was given 15 minutes to read, recite, sing or play an instrument. Some people performed as a group. The first act was often a member of the Clergy with a ‘worthy’ reading. The church choirs would sometimes sing but it was mostly ordinary townspeople who were standing up to entertain which must have added to the excitement and enthusiasm of the audience. As far as we can tell from newspaper reports at the time, the ladies were mostly involved in the musical entertainments. They would sing either a solo or a duet and they often accompanied the male singers on the piano. Some of the acts were cheered and clapped and there were shouts for ‘Encore’! Others received a slightly less enthusiastic response. People dropped out at the last minute but there was always someone willing to take their place. The readings might be old family stories, tales of the sea or taken from books of ‘Original Penny Readings’ that were published specifically for this entertainment.

In 1866 George Manville Fenn, a prolific author who had attracted the interest of Dickens, published a book entitled ‘Original Penny Readings’. It contained short stories particularly suited to Penny Reading performances such as, ‘A Life In A Minute’ or ‘After a Blast’ which was a dire tale of a miner who has a row with his wife before leaving for his shift and then being caught up in an explosion! All of the stories we found were written for male voices, so it seems likely the gentlemen were expected to do the readings. The most popular tales were reported as being those that were comical or from the pen of Charles Dickens himself. ‘An extract from Dickens’ ‘A Christmas Carol’ was traditionally read during the Festive Season, and in 1867 George Manville Fenn produced another collection for the populace, entitled ‘Christmas Penny Readings’.

Any events that sold well and brought in high revenue were very popular with the Institutes Committee. The Penny Readings appeared to have sold well and must have been very economical to put on. There were no professionals to pay. The members of the Committee had the unenviable task of raising money from all their organised events to enable them to pay the rent to Deal & Walmer Public Rooms Co Ltd and to continue to enhance the venue with both improvements and redecoration. The minutes of their annual meeting were published and it’s clear to see they struggled to break even at the end of each year. At each Committee Meeting it is evident they spent many hours discussing how they might increase the Institute’s revenue.

Subscriptions were a good source of income. Residents of the town could become subscribers to the Reading Rooms only or to the Institute only, or both. There were special rates for schools and families. Visitors to the town would be admitted to the Reading Rooms on payment of one penny.

The Institute was supported by many local dignitaries such as The Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, Viscount Palmerston and his successor the Earl Granville. Local members of Parliament were requested to give their support too and prominent residents in the local area.

The committee decided to issue a monthly journal reporting on the events that were held at the Institute and promoting those that would take place throughout the coming weeks. Many lectures were advertised on subjects such as literature and science plus the ever-popular Penny Readings and ‘A Spelling Bee’ which was another event that brought in the crowds. The young men in the Association were keen to have a ‘Bagatelle Board’ installed in one of the rooms. The local Amateur Dramatic Society from Dover performed to a very appreciative audience in 1871 which inspired some people to suggest Deal might form a Deal Amateur Dramatic Society. Visitors to the town wrote letters to the local newspaper praising the events available to them during their stay. There is no doubt the Institute was a huge success and an extremely popular venue throughout the town and surrounding area.

Unfortunately, in the year 1873 alarm bells started ringing as to the financial viability of the venue. What a crushing blow it must have been to the members of that hard working committee but, on March 1st of that year, attention was called to the position of the Institute. Despite all their successes the venue was losing money. They were, financially, in trouble. More support from the townsfolk was required if they were to continue to pay the rent and ensure their survival.

Someone on the committee had the idea of appealing to local wealthy citizens. Dr George Redsull Carter was a native of the town and not only a doctor but a poet too. He was widely read and travelled. His monetary contributions to St George’s Church were frequent, as he installed memorial tablets in the church to both of his parents and replaced the organ. After his death in 1879 another memorial was installed in his honour. Before his passing, however, the committee managed to persuade him to look kindly on the Institute and he donated a sum of £500 and the contents of his library. He asked if his name could be added to that of the Institute and so the building was duly renamed The Carter Institute. At this point in our research, we can find no connection between George Redsull Carter and the famous Elizabeth Carter of Deal but the local newspaper informs us that many of the lady’s valuable relics, which may have been stored at the Town Hall, were now to be under the care of the Carter Institute.

Despite this injection of cash, and the continuation of the entertainments, the Carter Institute struggled. By 1884 the committee reported that there seemed no longer to be the desire by the local people to frequent the Institute.

Classes, given in line with the edicts of the Deal Improvement Society, were lessening in importance as the state gradually took over more and more responsibility for the education of both the young and those adults keen to improve their knowledge. They resisted paying professional companies to perform in the large Assembly room, preferring to use local, amateur companies, (yes, Deal did eventually form its own amateur dramatics company!) where they could both charge for the use of the space and take a percentage of their profits.

It is reported in the Committee minutes of 1885 they had now, ‘virtually ceased to arrange for entertainments and were giving special attention to the Reading Room and the Recreation Rooms’. When it came down to it, reading the national newspapers and playing Billiards and Bagatelle was all the entertainment the local population required. The era of all those crowded rooms and squeezing past the ladies’ crinolines had sadly passed into history.

By 1893 the responsibility in connection with the classes passed entirely to the Education Authorities and the Institute had become, effectively a ‘Social Club’ with just the Reading Room, Library and a Billiard Room.

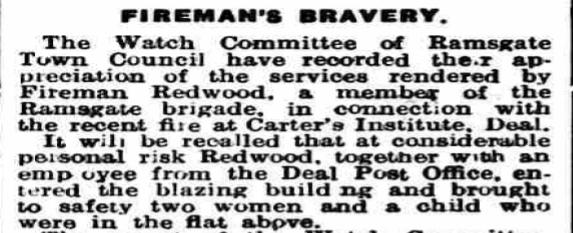

In 1903 the Carter Institute transferred to a much smaller building at 79, High Street. This house had once been the home of Mr Iggulden, a local brewer (easily identified by locals today as the large house at the rear of where Rooks the Butchers traded). During the 1914-18 war, the Institute was frequented by a very large number of men in the Naval, Military and Air Services, who were admitted free of charge. It is documented that thousands of men used the facilities on offer. In March 1931, the building experienced a devastating fire which gutted the premises, and it was reported that many of the valuable relics from the Elizabeth Carter collection were sadly lost.

The elected Committees continued to oversee the Institute until, at least, the end of the 1950s. We have yet to discover a record of when the Carter Institute finally closed its doors. We can only speculate that, with the arrival of the ‘Swinging Sixties’, the facilities offered by the Institute became outdated and no doubt rents for buildings in the High Street soared and became untenable.

We have nothing but admiration for all the local residents of Deal and Walmer who carried out such an amazing job on those committees throughout the decades as they tried to keep abreast of new entertainments and interests and gave of their time and energy so selflessly to enrich the lives of people in our town.