Follow us on Facebook @FHofDW

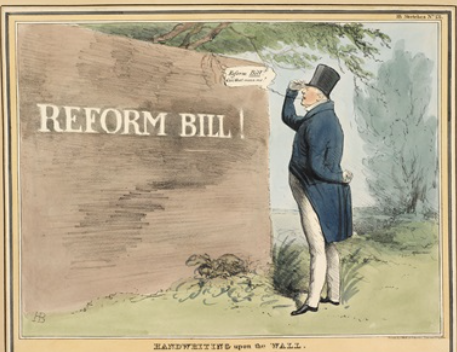

Deal & Walmer and the 1832 Reform Act

In the 1430s an act was passed that enabled all owners of freehold property or land, with a value of 40 shillings, to vote in the county in which they lived. This voting system was still in force in the early 1800s and by that time it meant that roughly only 435,000 people out of a population of over 24 million in Britain had a vote. On the whole this meant the upper class landed men and Freemen, though in a few rare cases women could vote if they owned property.

In 1832 an Act of Parliament was passed that would change this old electoral system. This was to become known as the Reform Act or the Representation of the People Act. The events that led up to this were many and varied and affected the whole of the country the route cause though, was poverty.

The Spreading of News

Printed newspapers and news-sheets had been in circulation since the printing press arrived in Britain in the late fifteenth century. So for those who could buy them they were purchased and taken home to read in private. Others were read and discussed in coffee houses, public houses or any other place where people gathered. Deal & Walmer did not have their own newspaper until 1858 so locals probably read one of several printed in the county, for example the Kentish Gazette or the Kentish Weekly Post and of course some from further afield would have found their way into the towns via the shipping in the Downs.

Education

Many people were illiterate or simply could not afford the 7d (in 1830) to buy a newspaper. A small loaf of bread was one or two pennies, so why waste money on news when putting food in your childrens’ mouths was far more important. So for these people the news may have been read out loud and discussed in the local hostelry or in Reading Rooms and in this way events, happening elsewhere, whether near to home, from across the county, the country or from abroad reached the ordinary man walking along Deal & Walmer’s streets.

With the growth of Church and Charity Schools illiteracy declined, opening up the possibility for people to read, question and challenge what was being said and done supposedly for and on their behalf.

Here in Deal & Walmer, like elsewhere, Churches had run Sunday Schools but by the 1790s Charity Schools were opening.

War and Prosperity

In 1793 Britain was once again at war with France. While this took many men willingly and unwillingly from their homes and did bring hardship to individuals and families, it also brought prosperity. Because of the proximity of Deal & Walmer to the continent, it became a mustering point. Naval and Military men literally filled the town. The civilian population prospered by providing for the needs of the thousands of men assembling here. Women came too, mainly as the wives, family and servants of the officers. The lower classes of women would also have come to see their men and there can be no doubt that there were many females who came to offer other services and comforts to those men willing to pay for what was on offer. This mass of people would all have been spending money, paying for lodgings, food, drink, clothing and entertainment. The breweries profited by providing not only beer to those in the town but to the ships off shore as well as clean fresh water.

The towns boatmen also prospered by ‘hoveling’, taking passengers, mail, goods and anything else to and from the ships anchored in the Downs and then there were the thousands of troops who all needed ferrying out to the ships waiting to take them to the Continent.

With so much shipping so close to each other accidents occurred, so they assisted vessels, that had lost anchors and ropes by taking out replacements and salvaging what was lost. There was the money gained from rescuing those in need too. Some of the boatmen were Sea Fencibles earning a few shillings every time they mustered. The Naval Yard provided employment for local men, as did the local boat builders and ropemakers. And of course there was always a bit of smuggling on the side.

Consequences of Victory in Deal & Walmer…

When, in June 1815, Wellington and his allies finally defeated Napoleon’s forces, at the Battle of Waterloo, it was celebrated far and wide with bonfires, fireworks and general partying and it can be assumed that Deal & Walmer celebrated too.

However following a rise there is always a fall and while the country celebrated, few working class people could have prepared themselves for what followed.

Deal, in particular, literally went into a rapid decline. Gone were the vessels waiting to ship the army across the channel and gone were the mass of naval and military men spending their money in the town. Everybody from the surrounding farmers who provided the millers with corn to grind, of which there were at least four in or around the towns, who sold the resulting flour to the bakers to make bread, to the pot boy earning a bit extra from the freely tipping soldiers in the local public houses, suffered from the loss of income. The ordinary townsfolk suffered the most and by the late 1820s they were impoverished.

…And Across the Country

Just as the rest of the country celebrated Napoleon’s defeat, it too suffered. The end of the war came with the demobilisation of over 300,000 soldiers and sailors who would all be looking for work. Many of these men, once hailed as heroes, carried injuries that made employment difficult to find or maintain.

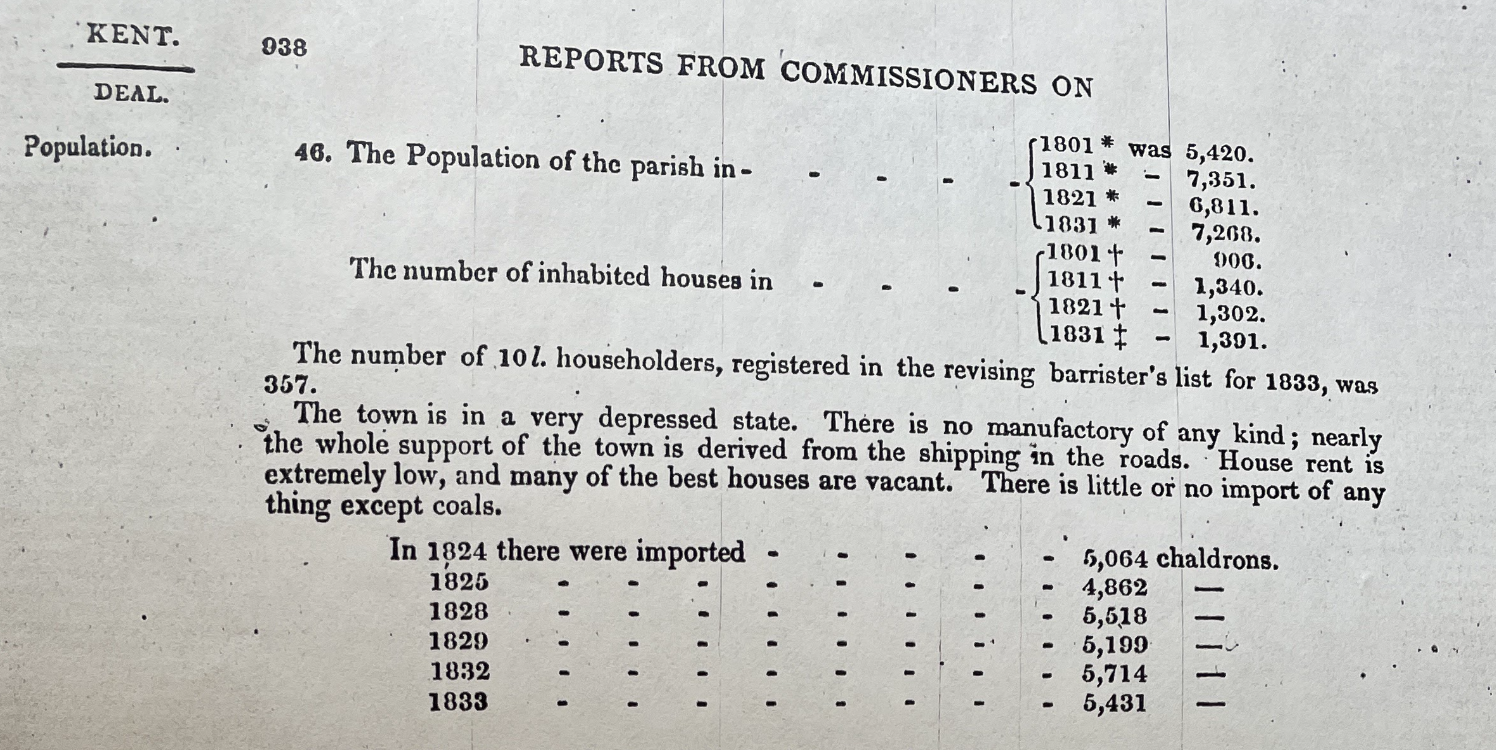

In addition to this situation there was the introduction and rise of factory and agricultural machinery and the use of cheap child and female labour. Countrywide the population growth also increased. In Deal & Walmer it fluctuated, between an estimated 5,000 and 8,000 people.

A greater population meant more mouths to feed and with less work this led to discontent among the working and lower classes. By the end of the 1820s, the upper classes and those in government began to be concerned about the number of protests and riots occurring across the country; the alarming news from France of riots there increased fears of revolution in this country.

The Corn Laws

At this time most of those with any political authority were rich landowners. They were often M.Ps or sat in the House of Lords. And as it was they, who were in parliament, they had the exclusive right to help pass legislation. In other words they protected their own interests by passing laws such as the Corn Laws.

Poor Relief

The high unemployment put a strain on the parishes trying to care for their poor through the Poor Rates. Supervised by a Justice of the Peace, the rates were initially collected and administered by men of the parish who were annually elected or even just selected to act as unpaid Overseers. Sometimes the ‘relief’ was provided in the form of financial support but fuel, food and clothing were also given to relieve the individual or families needs. Part of this strain was caused due to the increased unemployment which reduced the number of people able to pay the ‘rates.’ In Deal, according to evidence obtained from the Vestry Clerk by Captain Edward Boys, there were 268 Boatmen paying rates in 1815 but by 1833 only 33 could afford to do so.

Walmer and Deal

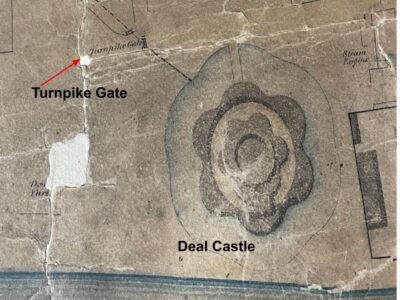

Employment was supposed to be found for those who could work, and efforts were made in the parish of Walmer to find employment for those designated as ‘able-bodied poor.’ An Act of Parliament was granted in 1797 to straighten the road between Upper Deal and Worth. A Turnpike Trust was set up to administer the work, and Toll gates were erected to collect tolls for a period of twenty years. In 1818 a further grant of twenty-one years was given to extend the road. This led to some in Walmer Parish being employed in picking stones. However, the Vestry were later to report that they could not find enough work for all its unemployed who were, they said, becoming demoralised.

The Turnpike road in Walmer was the continuation of the road that ran through Deal from Sandwich. The Walmer section ran along today’s The Strand on to Dover Road so to Upper Walmer. As the road passed into and through Walmer, bars and chains were fixed at Deal Castle and at Upper Walmer. As indicated on an 1810 map of Deal.

The Turnpike road in Walmer was the continuation of the road that ran through Deal from Sandwich. The Walmer section ran along today’s The Strand on to Dover Road so to Upper Walmer. As the road passed into and through Walmer, bars and chains were fixed at Deal Castle and at Upper Walmer. As indicated on an 1810 map of Deal.

In 1834 Walmer Parish reported to the Poor Law Commissioners that the trade of the boatmen had finished in consequence of the many improvements in navigation.Emigration to places such as South Africa was an option for some; in 1821 a party of Deal Boatmen sailed for the Cape of Good Hope.

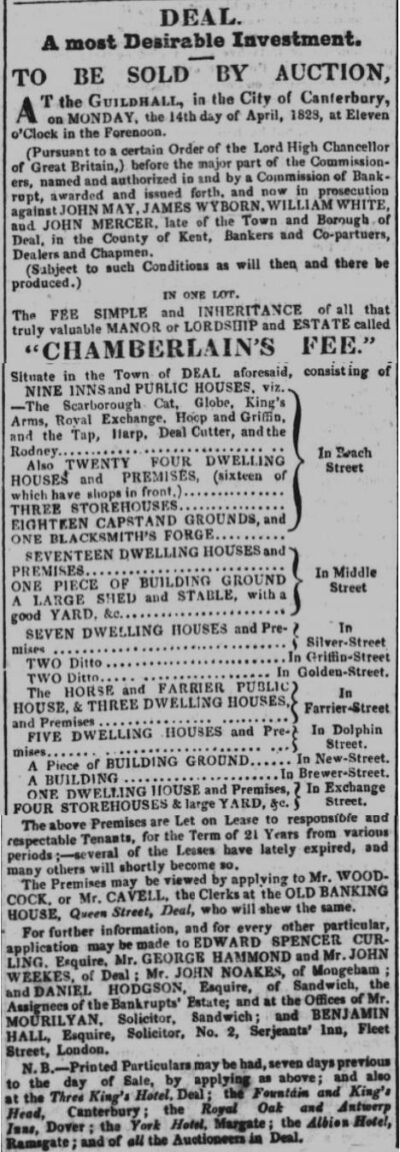

The downturn didn’t just affect the labouring and working classes of the town. Amongst the tradesmen there were bankruptcies including, in 1826, the bank of solicitor James Wyborn, William White, John Mercer and John May, the latter was then the Lord of The Manor of Chamberlains Fee which covered a large area of Deal. In order to pay off his debts John May, in 1828, was ordered to sell off his assets including what was left of The Manor of Chamberlains Fee.

Act of Parliament

In 1819 the Act to Amend the Law for the Relief of the Poor (59 Geo. III c.12) was passed. It told Vestries to distinguish between the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor. The latter group was deemed to be idle, extravagant and profligate. Salaried Overseers were to be employed and were to give better-kept accounts and either the building or the enlargement of workhouses. The Act now required two Justices of the Peace, instead of one, to agree on the Vestry giving poor relief.

As the number of the parish poor seeking assistance increased the cost to the ratepayers rose alarmingly especially as the payments were calculated by the ever increasing cost of bread and the number of children in a household. As it became harder to get relief, distrust in the Poor Law and in those who administered it grew. A need to be able to influence the law makers, to have a say, a vote, was increasingly being voiced by those who had no say at all. No wonder anger and fear for the future boiled over.

Peterloo Massacre

Discontent and unrest spread and in desperation to be able to afford to feed themselves and their families people tried to influence change. Public gatherings and protests were arranged which in some instances led to violent protests. The most notorious of which occurred in 1819 in Manchester.

It began as a peaceful demonstration where an estimated 60,000 working-class people from in and around Manchester marched to St. Peter’s Fields. To our modern way of thinking their demand was simple, they wanted the vote for every man, regardless of income, at annual elections. The local magistrates were terrified by this mass of people, so they called in the Army to arrest the leader, Henry Hunt, and remove the protesters who stood little or no chance against armed soldiers, many of whom were on horseback. More than 650 were injured and at least 18 died, one an unborn child.

Manchester at this time, despite having a population of over 120,000 did not have an M.P. to represent its people in Parliament.

The government still did not listen but simply passed new legislation to prevent any future disturbance. The so-called Six Acts were aimed at suppressing any meetings for the purpose of reform.

OTHER FACTORS

At the end of the war, the government cancelled its contracts, leaving the war industries dependent on them to find their own solutions. These events obviously affected those working in those industries, but they all had a knock on effect. Basically the money used to build business, to buy services and to pay workers was not there. That being so it was the working man, the agricultural labourers, the factory workers and in the coastal towns that relied on the shipping, such as Deal & Walmer, the Boatmen who paid a heavy price.

Mechanisation

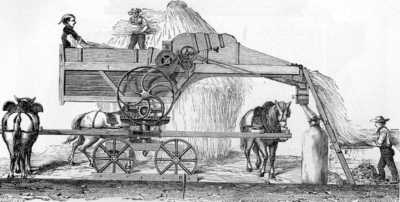

In the countryside mechanisation was spreading. Threshing and reaping had always been done by hand. For the farmer this was expensive so obviously they looked to reduce costs. One local man, John Boys of Betteshanger in the early 1800s, did so by inventing his own horse driven threshing machine. This meant that wheat could be harvested and threshed on one day, ground into flour the next and the following day made into bread. Good for the farmer, the miller and baker but not for the agricultural labourer. Nonetheless the use of agricultural machinery spread.

The Weather

The years 1828 to 1830 saw poor harvests. In June, July and August 1828, there were heavy rains, which damaged the wheat before and during harvesting, in October there was snow. The Spring and Summer months of 1829 were wet and cold, and the corn harvested that summer was of poor quality. The Winter of 1829-1830 was extremely cold, and the Summer of 1830 was also wet, but at least in that year there was a harvest that could be brought in.

This was obviously disastrous for the agricultural communities. Meagre crops not only meant less food but to the agricultural labourers in particular it meant little or no work.

The civic-minded people of the towns set up soup kitchens and other charitable activities to feed those in need.

Deal & Walmer

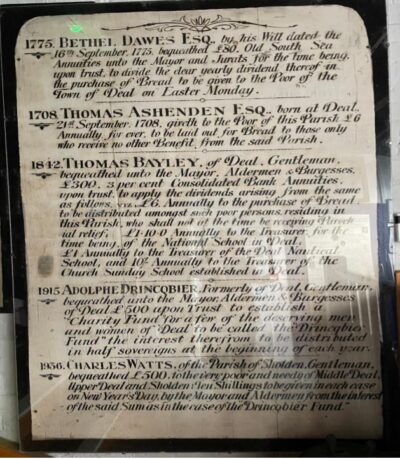

In Deal & Walmer, from at least 1700, there were wealthy benevolent people who had left trusts to donate money to the needy poor or to provide them with bread. Despite these acts of charity people still suffered and did whatever they could to feed their families, including smuggling.

Smuggling

As elsewhere along the coast, there was a rise of the age old trade – Smuggling. During the war years Smuggling had never gone away, those involved not only brought in illicit goods but also intelligence and aristocrats escaping France. To the continent they delivered spies and ran gold guineas to France and not just in the support of the British.

Towards the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon allowed English smugglers entry into the French ports of Dunkirk and Gravelines and encouraged them to run contraband back and forth across the Channel. The smugglers then took escaped French prisoners of war, gold guineas, and English newspapers to France; and returned to England with French textiles, brandy, and gin.

Napoleon himself apparently held the smugglers in high esteem, as it was from them he also received his valuable intelligence. He reportedly said of the Kent smugglers “They are a terrible people with the courage and the ability to do anything for money.”

Following the wars, when hardship started to bite, the smuggling industry could, for some, provide a much needed income. At this time a labourer earnt less than eight shillings a week but, on just one night, for carrying smuggled goods off the beach, he could earn himself ten shillings.

In around 1815 the government decided, yet again to act, and Captain William McCulloch was sent to Deal area where he famously said that he will “…make the grass grow in the streets of Deal…”

William Cobbett Visits

William Cobbett was a farmer, journalist and an M.P. He believed that reforming Parliament would ease the poverty of farm labourers and strongly opposed the Corn Laws.

He started a magazine called The Porcupine and later launched Political Register, which was often critical of the government. In 1809 he attacked the use of foreign troops “…four legions of German Legion Cavalry…” to put down a mutiny amongst the Local Militia of Ely.

For this criticism he was arrested, tried and convicted for sedition and sentenced to two years in Newgate Prison. Not deterred on his release he continued to print Political Register, even reducing the price and so turning it into the main newspaper for the working class.

In 1817, it was rumoured that he might be arrested again for sedition, so he fled to America but, with help of a friend in London, he continued to print Political Register. He returned to England, in late 1819 by which time his finances were depleted but he steadfastly remained politically active, demanding freedom of speech and Parliamentary reform, advocating non-violence.

He is best known for his Rural Rides which he started in 1821. He later wrote that his purpose was to hear ‘what gentlemen, farmers, tradesmen, journeymen, labourers, women, girls, boys, and all have to say; reasoning with some, laughing with others, and observing all that passes.’ By voicing his and their opinions, he was again tried for sedition in 1830 but this time he was acquitted.

On his visit to Deal in 1823, he wrote

“Deal is a most villainous place. It is full of filthy looking people. Great desolation of abomination has been going on here; tremendous barracks, partly pulled down and partly tumbling down and partly occupied by soldiers.Everything seems upon the perish. I was glad to hurry along through it, and leave its inns and public houses to be occupied by the tarred and blue-and-buff crew whose very vicinage (vicinity) I always detest.”

This description of the state of Deal and its people reflects the dire situation that the “… filthy looking people…” of the town were in.

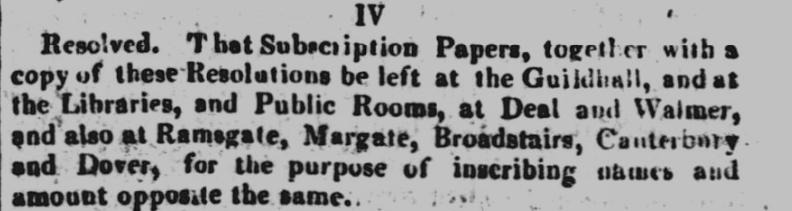

The Deal & Downs Regatta

In an attempt to bring some much needed relief, both emotional and monetary, to the town it was decided to hold a regatta. So by the efforts of the great and the good in the town The Deal & Downs Regatta was launched in 1826. Paid for by subscribers from Sandwich Dover and Thanet it brought in, according to the Kentish Weekly Post 10,000 people to the town.

Considering this was before the railway in Deal this was no mean feat. Most must have come on foot, carriage or sea. It is remarked,by a report in the in the Kentish Weekly Post, that at least 300 came from Canterbury alone! Prize money was offered to encourage boatmen to participate and added to the excitement of the contest and the need to win.

Throughout the day the town’s many public houses and hotels provided refreshments, then at the end of the day, as many more people required food and drink before returning home or to their lodgings, the towns folk opened up their homes to offer sustenance and so earned themselves a little money.

Such was the success of the day that the Regatta and the carnival now associated with it continues to this day.

This one event, annual though it became, could not alleviate all the poverty in the town and certainly not amongst the boatmen.

Sir Edward Knatchbull

Sir Edward Knatchbull was called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn in 1803. In 1819 he succeeded in the baronetcy on the death of his father, who was also the MP for Kent. His fathers death, therefore, caused a by-election at which Sir Edward was duly elected. He held the seat until the 1831 general election which he did not contest.

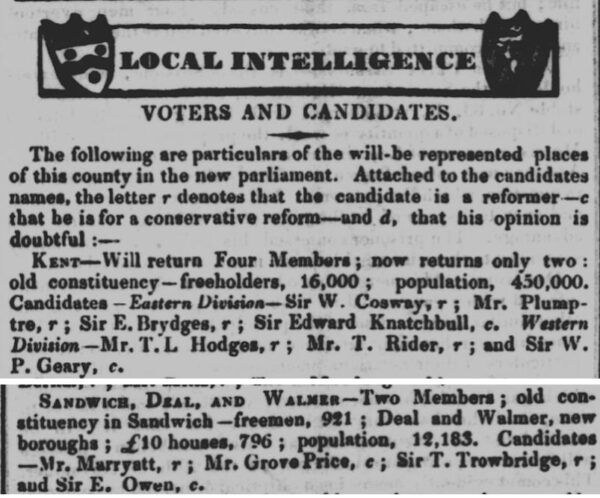

The Reform Act 1832 split the Kent county constituency into Eastern and Western divisions, and at the 1831 general election Sir Edward was elected as one of the two M.P.s for the new Eastern division of Kent. He held that seat until his resignation in early 1845.

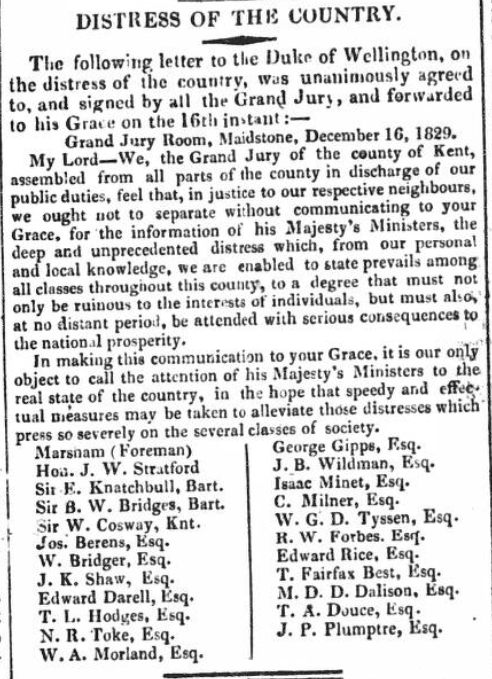

Across Kent

In December 1829 the magistrates of Kent, through M. P., Sir Edward Knatchbull, sent a letter to the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, requesting that he take action to help the county stating “… the deep and unprecedented distress which, from our personal and local knowledge, …. prevails among all classes throughout this county…” and hoping for “…speedy and effectual measures may be taken to alleviate those distresses that press severely on the several classes of society…”

This appeal seemed to have fallen on deaf ears.

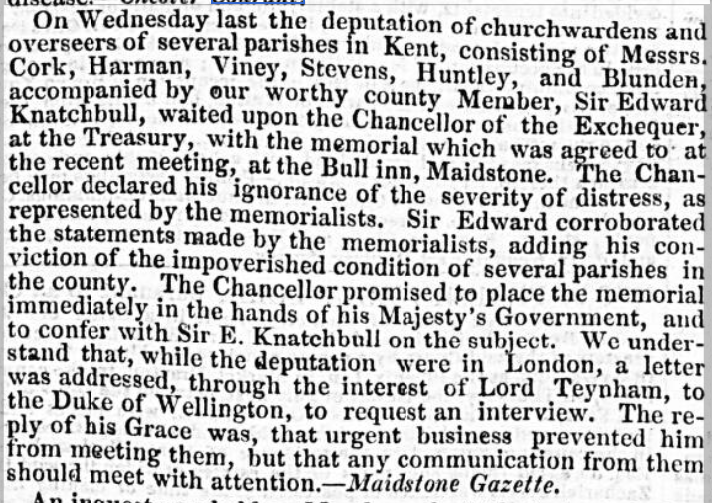

In June 1830 Sir Edward Knatchbull again tried to bring to the attention of those in power of the appalling situation the labouring classes of Kent were under. He, with several churchwardens, visited Henry Goulburn, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, presenting him with a memorial or petition. Henry Goulden though declared his ignorance of the severity of the distress being suffered!!

According to one survey, in the last months of 1829 and the beginning of 1830, there were 54 petitions or memorials presented to Parliament from Kent alone. All attesting to hunger, loss of income and businesses. Some had been signed by 1,000’s.

Monarchs and The Politics of Reform

From 1815 there was a period of relative calm but when Charles X acceded to the French throne a series of events affecting the poor man of France, including those echoing what was happening here in Britain, such as the bad harvests and the downturn in trade, started to impact on the ordinary French people. The rise of the so-called Liberal Press, mobilised the people against monarchy and government. With the continued illicit cross channel trade news of the plight of France’s people and the renewed unrest there quickly reached the people in Kent who began to compare their own situations with their counterparts in France and the British establishment’s concerns for revolution increased.

Then, in July 1830, Paris mobilised and riots ensued. At the end of the month Charles X abdicated in favour of his son.

Here in Britain with the death of George IV in June and as William IV succeeded his brother to the throne, a general election, as a legal requirement at the time, was called.

The Duke of Wellington was then Tory Prime Minister and favoured by King George. The new king, despite his suggested Whig sympathies, reassured Wellington that everything should go on as before.

Polling began on July 29th and ended on September 1st. This had to be done openly, secret ballots were not introduced until 1872, so treating, bribery and intimidation was commonplace. It was not unheard of for voters to be dismissed from employment or evicted from their homes if they were known to have ‘voted the wrong way’!

This election brought the chance for Reform, and the people knew it.

The new Parliament was summoned on September 14th with Wellington again at the helm. Unfortunately, he did not, as Lord Grey said, understand the character of the times. He continued to defend rule by the elite, is answer to riots was military force and he saw no problem with the growing industrial cities lacking parliamentary representation. He also saw no problem with so-called Rotten Boroughs including uninhabited places, such as Dunwich in Suffolk, which had totally succumbed to the sea by 1740, and of Old Sarum which was basically just a hill with seven voters, each having two M.P.s! Such opposition caused his popularity to fall with crowds even gathering to throw stones at his London home.

The Emergence of Captain Swing

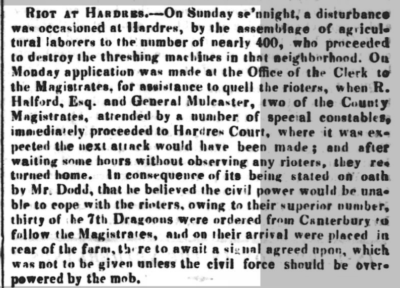

On August 28th, 1830, just two weeks before parliament was summoned, on September 15th, the first threshing machine was destroyed at Hardres. By the end of October more than 100 had been destroyed in East Kent alone. Across the county there were protests and riots over low wages and those captured and convicted faced imprisonment and, for some, transportation.

On August 28th, 1830, just two weeks before parliament was summoned, on September 15th, the first threshing machine was destroyed at Hardres. By the end of October more than 100 had been destroyed in East Kent alone. Across the county there were protests and riots over low wages and those captured and convicted faced imprisonment and, for some, transportation.

Captain Swing was not a real person, as many thought, but a symbol that represented the poor agricultural labourers. Warning letters were sent to farmers and landowners demanding increased wages and to desist in their use of threshing machines signed by ‘Swing’ or a ‘ Captain Swing’ One of the first letters to be sent was received by a farmer in Dover in early October 1830. More followed along with the threatened action that also included the burning of hay ricks and farms.

Initially, the magistrates were lenient. At the East-Kent quarter sessions in October 1830, Sir Edward Knatchbull sentenced seven machine-breakers to three days in prison. However, penalties became more severe as the uprising continued and on Christmas Eve 1830, at the Kent Winter Assizes, four men were sentenced and hanged at Penenden Heath, Maidstone.

For these crimes, during this period, a total of 19 people were executed, 505 transported to Australia and 644 imprisoned.

Threat of Riots in Deal

While letters were being sent by Captain Swing elsewhere, in Deal at the end of October 1830, Mayor Benjamin Hulke wrote to the Home Office saying

“… I have reasons to fear that there is a likelihood of a serious Disturbance probably bloodshed within my jurisdiction …by the Boatmen…”

The Boatmen, who he described as “… A very numerous and determined people…” he says were planning to destroy the Cinque Ports Pilot cutter.

Mayor Hulke ended his letter expressing his concerns about the lack of ability of the civil powers to deal with any disturbances particularly with the “…disturbed state of this neighbourhood when outrages are daily being committed to the terror of everybody owing the Threshing Machines…”

He requested, but was denied “… a sufficient force of Dragoons or Infantry should be stationed in readiness at Walmer Barracks…”

Cinque Ports Pilots

At this time the Pilots had lookouts on the shore to watch for signalling flags from passing ships requiring their assistance. They would then row out to the ships in their own cutter; a type of sailing boat used to deliver and collect pilots to and from the merchant vessels. Later they cruised the coast in their cutters on the look-out for a ship requiring a pilot.

Pilotage regulations had been introduced in 1808, 1813 and in 1826. These ‘Acts of Parliament’ put the power into the Pilots hands to “…supercede any licensed boatman who may be conducting a ship from the Westward into the Downs, without the boatman having any claim to one shilling of remuneration…” in other words if a licensed boatman offered his services when a pilot was not available a ships master could accept him however, if a Pilot then came aboard the boatman then was not entitled to any remuneration at all.

The use of Pilot cutters also meant loss of revenue for the unlicensed boatmen who would previously have been employed to ferry Pilots out to awaiting vessels signalling for a pilot and also those on shore who would be paid to help launch and beach the boats.

Licensed Boatmen and their Boats

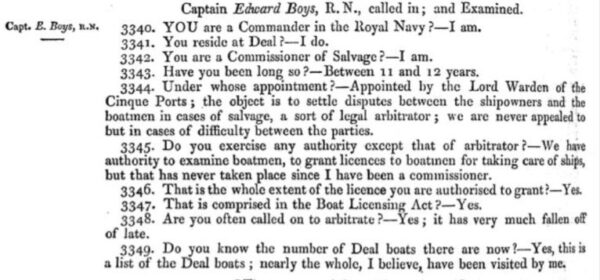

A boatman was licensed under an Act of Parliament which stipulated how far they could legally take their vessels along the coast to offer services to passing shipping, including piloting. They could not go as far as France or Holland though, supposedly to curtail smuggling. Licences were granted by a Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports representative who could also examine the boatmen. In Deal this fell to Captain Edward Boys who was also the Commissioner for Salvage. Although not having an official qualification it became the practice for captains and masters to give letters, or notes of recommendation, to boatmen who had piloted their vessels.

Plight of the Boatmen

The boatmen finally had their voices heard in 1833 following a petition to Trinity House signed by seven boatmen from Deal, on behalf of their peers; this led to a Select Committee inquiry to investigate the boatmen’s claims. The resulting evidence showed the desperate situation the boatmen and their families had fallen into following the end of the wars.

Edward Darby, Clerk for the shipping agency of Messrs Igullden who were agents for the East India Company stated

“…it is deplorable; the men have not a shift of clothes (change of clothes) . . . they have no fires to sit by, and not sufficient animal food…”

And Joseph Marryatt Esq. M.P. said “… The state of the boatmen, I can assure your lordship is generally speaking, deplorable. They are pennyless and too frequently without food or sufficient clothing ….”

Conditions in Dover were equally bad, and the evidence given was even more telling. Those giving evidence as to the living conditions of the boatmen stated that “…where they once had kept their houses well furnished and themselves well clothed, they now found themselves in such a state of poverty that they were unable to go to sea for want of a change of linen in wet weather…”

According to Mr. T. Robinson, manager of the Dover Benevolent Society he said “…furniture they have none, and their apparel by day serves to cover their innocent babes by night…” Blankets were loaned out locally during the winter months but had to be returned in Spring.

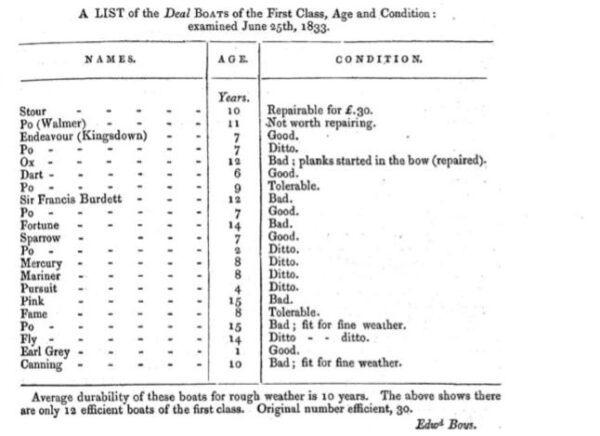

Captain Edward Boys also presented the committee with a list of just the first class boats he had recently examined. This showed that the number had dropped from thirty to twelve, and many were only just seaworthy.

Captain Edward Boys also presented the committee with a list of just the first class boats he had recently examined. This showed that the number had dropped from thirty to twelve, and many were only just seaworthy.

Was it any wonder then that the boatmen had considered taking matters into their own hands?

Not all can be blamed on the Cinque Ports Pilots. The replacement and use of chains instead of hemp cables for anchors added to the distress. Chains were less likely to part under stress than hemp; this meant a loss in income to the boatmen as they assisted ships who had lost their anchors and cables by taking out replacements. They would have then also trawled the sea bed for what was lost, thus earning themselves salvage money.

Stephen Pritchard, writing in the 1860s, described how “…many thousands of pounds annually used to be paid for hemp cables and for the loss of anchors, which has become a comparatively small matter now…”

Back to politics

The continued unrest and the Tory government’s inability to do anything about it caused Wellington’s government, in November 1830, to lose a vote of confidence. The Duke resigned and the Whig, Earl Grey was then asked to form a government.

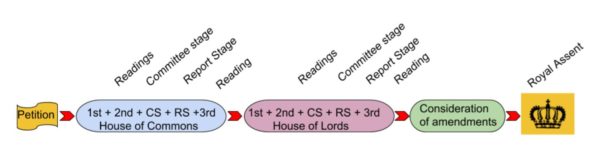

The First Reform Bill

With the Whigs, under the leadership of Earl Grey, now in power the first Reform Bill was presented to the House of Commons in March 1831. It passed by one vote but it failed to get through the House of Lords. In response, knowing the voice of the people, Earl Grey asked the King to dissolve parliament to bring about a general election. After some persuasion The King assented and declared “ …I have been induced to resort to this measure for the purpose of ascertaining the sense of my people…” Grey won a landslide victory.

In Deal & Walmer

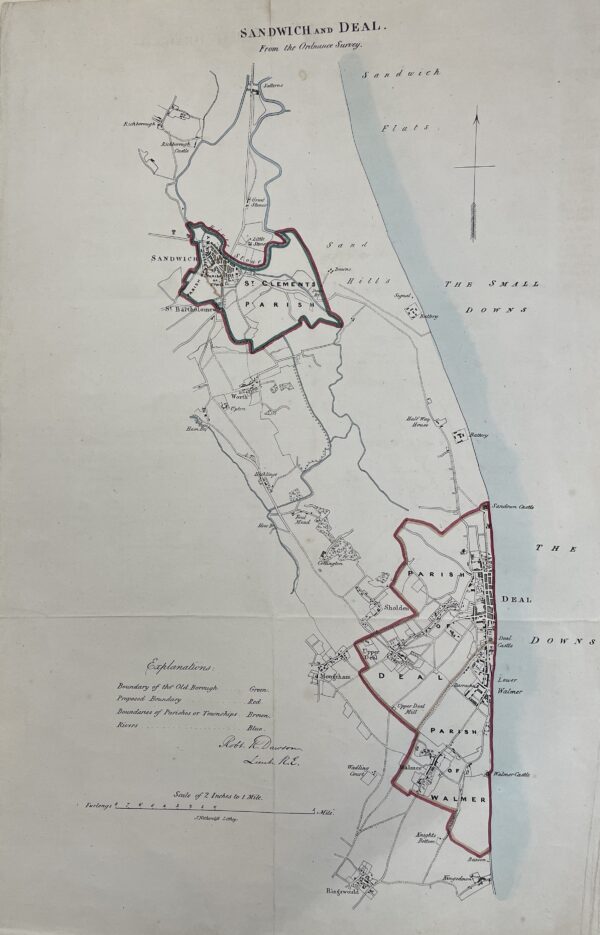

Sandwich at this time had two M.P.s and Deal & Walmer watched on as the election was fought out between the Whigs, Sir Edward Thomas Troubridge and Joseph Marryat and the Tory, Samuel Grove Price. On May 6, 1831, Sandwich declared for both Whigs, Sir Edward Thomas Troubridge and Joseph Marryat .

Soon after Sir Edward visited friends in Deal. His arrival was a cause of celebration. According to the Kentish Weekly Post, he was met outside the town by “…a vast concourse of respectable inhabitants of the town…” the ‘truly loyal boatmen’ then insisted on taking the horses from his carriage and drawing him triumphantly through the town. Once a circuit had been made, they arrived at the Royal Oak in Middle Street, before going in to dine, Sir Edward thanked the crowd and the boatmen in particular.

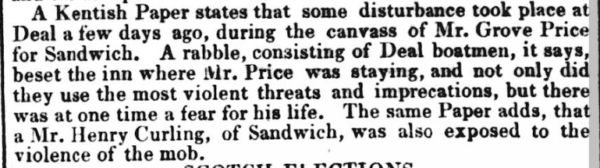

The week before though, Samuel Grove Price received no such reception. When he attempted to canvas Sandwich Freemen, resident in Deal, by holding a meeting at the Royal Oak, he and his friends were assaulted by a ‘rabble’ of boatmen.

The Coronation

On September 8th, 1831, the coronation of King William IV took place so, for a few days at least, there was rejoicing in the streets. The King had wanted a modest Coronation which upset many of Tory Peers who actually threatened to boycott the Coronation entirely! The King though was not to be swayed and in the interest of keeping the costs down there was no Coronation banquet afterwards.

The Second Reform Bill

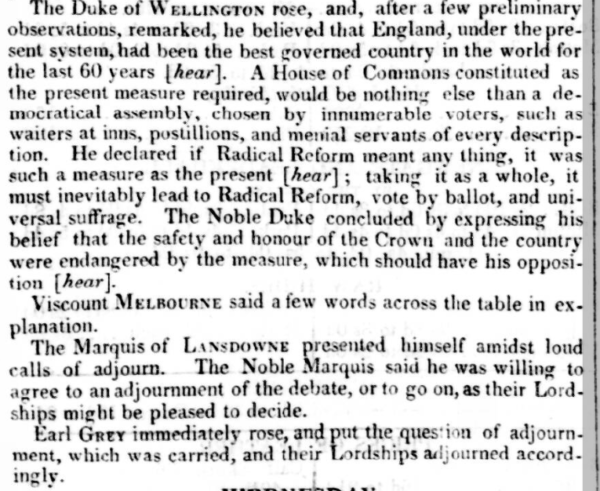

Then on September 21 the third reading of the Second Bill took place in the House of Commons. It finally had a majority vote of 345 in favour to 236 against. The Bill was then debated in the Lords during the first week of October, with many petitions for and against, being read out from across the country. However, the Bishops of the Church of England, known as the Lords Spiritual, assembled in an unusually high number and of the 22 voting, 21 opposed the bill.

Yet again this second Bill was rejected by the Lords. When the result was heard by the people violence erupted in towns and cities. In Bristol the city’s four jails were torched. In London, those who voted against the bill, including the Duke of Wellington and bishops had their homes attacked.

“What have the Lords done?” asked The Times “… The nation willed it. The Lords forbade it…”equating to 400 people versus twenty-two million, they asked “…Will the nation give way or will the Lords…?”

On 12th October a march was organised in London of over 300,000 people. Their intention was to present a petition to the King. This caused great alarm at the palace and eventually the leaders were persuaded to present their petitions to M.P.s at St. James Square instead. Later that evening a meeting was held and eventually a delegation went, uninvited, to Downing Street where they met Earl Grey to demand that he pass the bill in seven days by simply creating more peers. The current House of Lords was then heavily biased towards the Tories.

As the matter was considered and very tentatively debated between the king and his ministers William IV brought the current session of Parliament to an end, or Prorogued it. Riots and countrywide violence continued, sadly leading to yet more innocent deaths.

Parliament was recalled, and the Bill was again presented and debated in the House of Commons. It passed with a majority of 164. Clearly the thought then was, would the Lords reject it? It was therefore vital for new supportive peers to be considered. As the Constitution said that the creation of peers was a royal prerogative, the King would need to take action.

The Third Bill

In March 1832 the bill was presented yet again to the Lords. The Times suggested the need for 70 or 80 new peers to get the bill through. With no agreement on creating new peers, the inevitable happened, and the Bill again failed to get through the Lords.

On May 7 Early Grey announced that he had two choices either to resign or to go to the King and ask him to create peerages. Grey resigned. On the 9th the King asked Wellington to form a new administration. However, he would be expected to bring in some reforms. Wellington declared “…I am as much adverse to Reform as I ever was…” but declared he would make every effort to serve the King.

The country’s financiers began to be concerned over the prospect of total opposition to Reform. There was open talk during this time of civil war and revolution which caused a run on the banks.

The about turn that Wellington was expected to make was too much for some of his party including Sir Robert Peel, who was the Tory Leader of the House of Commons, who felt “… unable to enter into the Service of the Crown…” On May 15 Wellington realised that he had little hope of government and controlling the Commons and went to the king. Later that day Earl Grey received a message from the King expressing his hope that the Bill could now receive modifications. Talks were once more about creating peers.

A few days later the King finally gave way and sent a letter saying that if there were continuing obstacles to the Bill, Earl Grey could send a list of peers sufficient enough to carry the Bill through the Lords. In the event it was not necessary the threat was enough as it appears messages were sent out against opposition. There were many abstinences. The Bishops did not vote, nor did some of the leading Tories of the day, including Wellington.

So it was that the Bill finally gained a majority vote in its favour in the Lords, and The Great Reform Act, the Representation of the People Act 1832, finally came into existence gaining Royal assent on June 7, 1832.

What Was Achieved

Following the act the franchise was extended but that still only meant 5 % of the country was able to vote. Previously it had been 3%.

Some Freemen, not living in the town they were freemen of, lost the right to vote and, as for the first time the act defined a voter as a ‘male person’ therefore, women totally lost that right.

- 56 boroughs in England and Wales were disenfranchised, or lost their M.P.s

- 31 were reduced to only one M.P.

- 67 new constituencies were created or gained M.P.s

- the franchise’s, or rights to vote, governed by property qualification in the counties were broadened, to include small landowners, tenant farmers, and shopkeepers

- A uniform franchise in the boroughs was created, giving the vote to all householders who paid a yearly rental of £10 or more and some lodgers

In Deal & Walmer

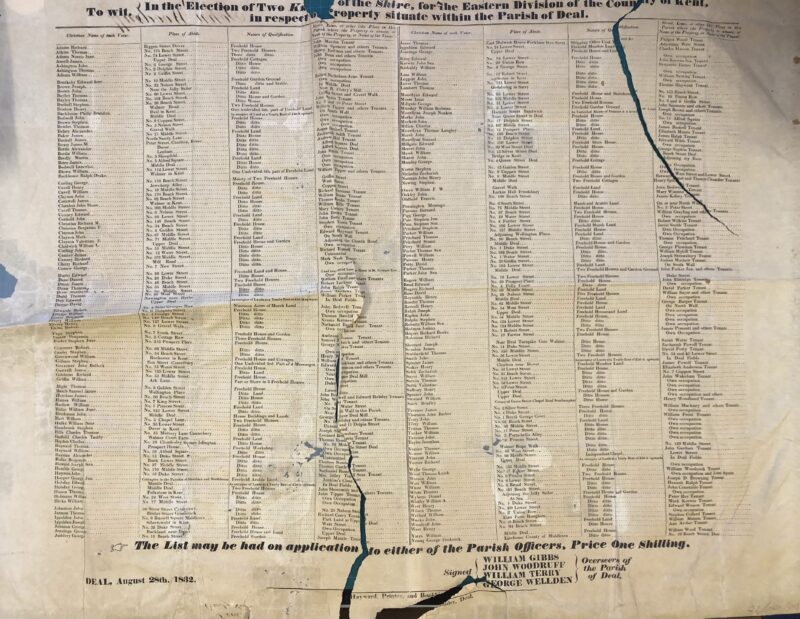

The Act also introduced a system of voter registration, to be administered by the overseers of the poor in every parish and township. The printer and bookseller Edward Hayward produced and printed a list of voters entitled to vote for the ‘Two Knights of the Shire, for the Eastern Division of the County of Kent in respect to property situate within the Parish of Deal’. This could be purchased for a shilling.

A General Election

With new constituencies a General Election was required and the candidates, who would run for parliament, were announced in September. Duly printed in the newspapers the candidate’s stance on Reform was also included. Parliament was dissolved in December 1832 and campaigning began.

The candidates for the newly formed parliamentary borough of Sandwich, Deal & Walmer were, Tories Admiral Sir Edward William Campbell Rich Owen and Samuel Grove Price and Whigs, Joseph Maryatt and Sir Thomas Troubridge.

With so much support for Reform in Sandwich, Deal & Walmer it was no real surprise that Joseph Maryatt and Sir Thomas Troubridge won this election and as such they became Deal & Walmer first parliamentary representatives. To celebrate a ‘Grand Dinner’, held at the Assembly Hall in Deal, was hosted by the freemen and electors of Deal

Such was the occasion that Mayor Edward Iggulden distributed a “…considerable quantity of bread and ale to the poor and a new silver coin to the boatmen…”

Following the after dinner speeches and toasts to the King, Joseph Maryatt gave his own short speech in which he spoke of the boatmen whom he “…considered as an oppressed and injured race of men…” promising to do what he could to help their condition.

Towards the end of the evening, it was announced that the Corporation had voted the freedom of Deal to both Joseph Maryatt and Sir Edward Thomas Troubridge.

In Reality

In reality little changed for the man in the street. Universal Suffrage and a secret ballot was hoped for they got neither. But, it had proved that the working man could put pressure on the government and change was possible.

Parliamentary reform continued to be called for and paved the way for further reforms. In 1867 the Second Reform Act extended the vote to all working men meeting the property qualification, this was still set at £10 this roughly doubled the electorate in England and Wales from one to two million men.

In 1872 the Ballot Act introduced secret ballots at elections for the first time other reforms followed including women regaining the right to vote in 1918 and importantly in 1928 The Equal Franchise Act was passed giving women equal voting rights with men.