Follow us on Facebook @FHofDW

Gabriel Bray

His Art, Fighting Smugglers

&

The Burning of the Boats on Deal Beach – or Not!!

On the Greenwich Maritime Museum’s website there are sketches of Deal that were painted in the 1770s by a Royal Naval Lieutenant, Gabriel Bray. Realising that Gabriel was born in Deal, we were naturally intrigued.

The often water coloured sketches, of which only a few are actually of Deal, give us a snapshot into the daily lives not just of the seaman he served with but with the people he saw on his travels and at home. There are seventy-five drawings in the collection held at Greenwich which are mainly dated 1774 to 1775. Other sketches and paintings can be found in the British Museum, the V& A and one is in the Royal Collection at Windsor. Many others hopefully are in private hands

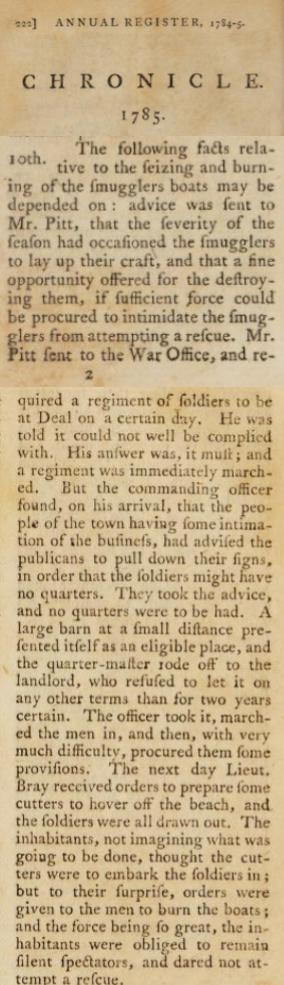

Looking into the man himself, to our surprise, we found that he was actually involved in the story of the Burning of the Boats on Deal Beach in 1784. So armed with that information we dug deeper. The story goes that in 1784, in an attempt to hamper the smugglers of the town, William Pitt ordered that the boats on Deal Beach were to be burnt, Lieutenant Gabriel Bray was to hover his cutters off the beach so giving a reason for the soldiers, recently arrived in the town, to come down to the shore at which point instead of embarking they were to burn the boats. This was reported as fact in The Times newspaper dated January 10 1785, and reprinted in numerous newspapers of the day including the supposedly reliable Annual Registerbut not as you might expect in the Kentish Gazette!

So where is the evidence for this event? There appears to be no other contemporary official reports to give credence to the story. That, with the fact that when, just some eight years later, William Pitt was made Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, taking up residence at Walmer Castle and in 1802 when he formed the three battalion-strong Cinque Port Volunteers, so he regularly came into contact with the local boatmen, come smugglers, there appears not to be any recorded retribution or animosity against the very man who supposedly ordered the destruction of their livelihoods. So with the opening statement, claiming that the facts “…maybe depended on…” left us suspicious and to question the veracity of the report.

While we waited for various documents to arrive from The National Archives we started to look into the Bray family.

Gabriel’s father, John Bray, was born in Deal in 1716 to John Bray (senior) and his wife Mary though it is not clear as to where they hailed from. It is possible that John (senior) was also born here in Deal to Daniel and Mary nee Winter in 1663, which would take the family back to at least 1662 as Daniel and Mary married in St. Leonard’s Church in August that year. John (senior) and Mary were certainly here in 1712 when a son, another John, was baptised, he sadly died the following year with no more baptisms of Bray children recorded in Deal until our John was born and baptised in St. Leonard’s on December, 4, 1716.

John entered the Navy in 1735 where he remained as a Lieutenant for twenty two years becoming a Master and Commander of the armed ship Adventurer in 1757. The following year the ship was attacked by the Matchault, a French privateer from Dunkirk. The action that took place lasted an hour and twenty minutes and despite several boarding attempts by the French and being heavily out gunned, John, by positioning his ship in such a way he was able to screen his men from musketry fire. Once the French submitted he found he had lost only one man whereas the French had sixty three killed and wounded.

He was then given the command of Princess Amelia and sent out to North America.

Naval war could be very profitable at this time for the crews serving aboard the ships of the Navy or Privateers. Captured enemy vessels were seen as prizes and once sold crews would receive a share of the ‘prize money’ depending on their rank. This could account for John being able to buy property in and around Deal as well as in the Hythe area and for paying for his two son’s education. We don’t know the financial status of John’s or his wife’s parents but prize money would certainly have helped provide a comfortable life for him and his family.

During the American Revolutionary Wars, 1775 -1783, he became regulating captain impressing men at Dover where he raised 6,000 men! He was eventually appointed Rear Admiral in 1789.

By this time his son Gabriel had been in the Navy for a number of years, a service he was destined to join. It seems that in 1763, aged fourteen, he spent some time as a volunteer onboard the “HMS Aquilon” under Captain Philip Perceval in the Channel. Perhaps this opportunity was arranged for him by his father as he didn’t actually leave Kings School, Canterbury until the following year. He had been enrolled at the school in March 1760 and was joined, two years later, by his brother John Raven.

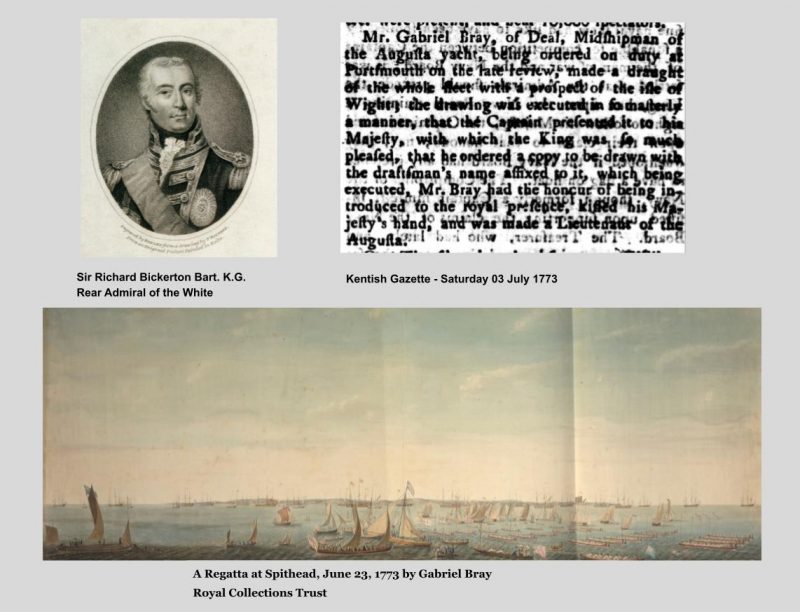

On leaving Kings he joined the Royal Navy as a Midshipman on board the HMS Launceston where, under the command of Captain John Gell, he spent much of his time in North America and Newfoundland before returning to home shores in 1773 to serve upon the Royal Yacht Augusta. In June 1773 George 111 reviewed the fleet at Spithead where Gabriel took the opportunity to record the event. His Captain, Sir Richard Bickerton, presented the sketch to His Majesty who, so impressed, ordered that a copy be made.This is now in the Royal Collection in Windsor Castle.

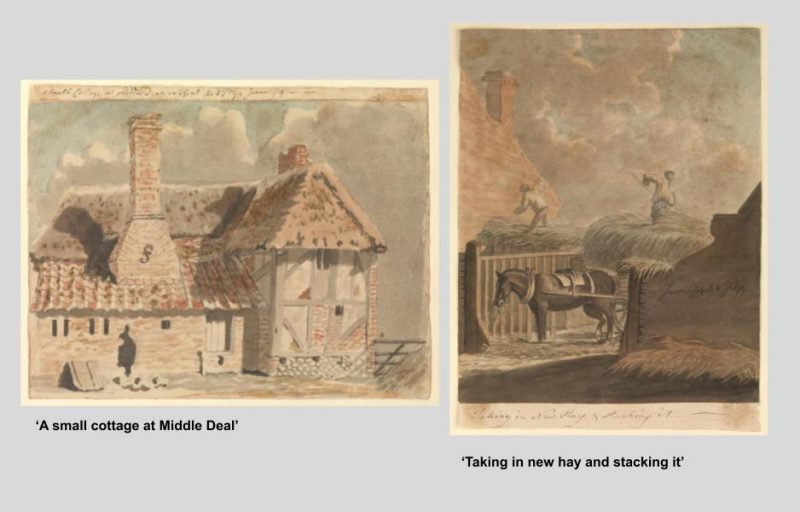

After his time on the Princess Augusta he returned to his home town of Deal, where on Half Pay, he continued to draw and paint. The following are some of those made during this time.

‘A Small cottage at Middle Deal’ shows a thatched wood framed cottage with brick infill and some flint at the bottom of the right hand wall. Of where this cottage actually stood or who lived in it Gabriel gives no indication but it was possibly built in the mid to late 1600s when brick became a popular choice of building material. Sadly by Gabriel’s time this once lovely cottage had fallen into disrepair.

‘Taking in new hay and stacking it’ shows two farm labourers doing just that. Again there is no indication of where this is but the building alongside it is built of brick and has a chimney so is possibly the farm house.

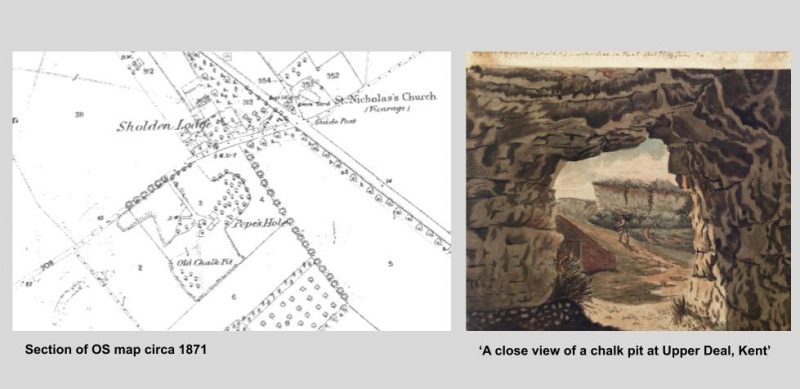

“A close view of a chalk pit at Upper Deal, Kent.” Quite possibly this was behind what is now Popes Hole known today as Popes Court. Chalk was used not only to provide lime mortar for building but was also used on the land as a fertiliser as a source of nitrates.

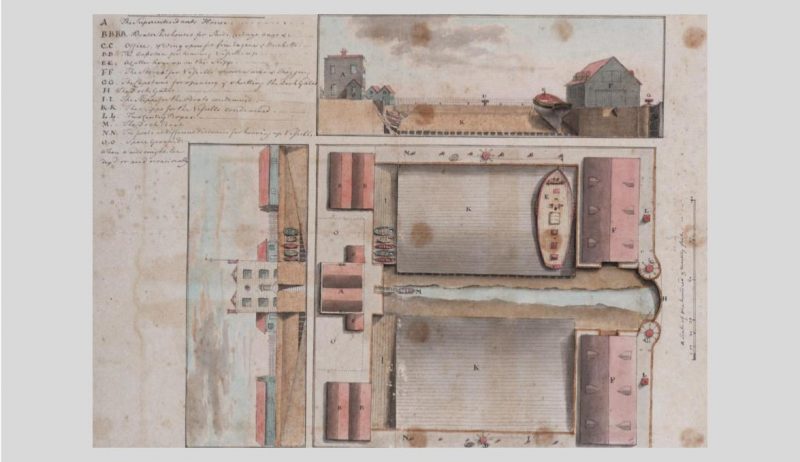

Whether Gabriel ever submitted this proposal for a small tidal dockyard to the Admiralty is not known but he has obviously given it some thought. The plan shows sloping slips to enable boats to be more easily brought in for repair and maintenance, store houses for sails and equipment, an area to dry sails, a seaward dock gate, as well as offices and the Superintendent’s House.

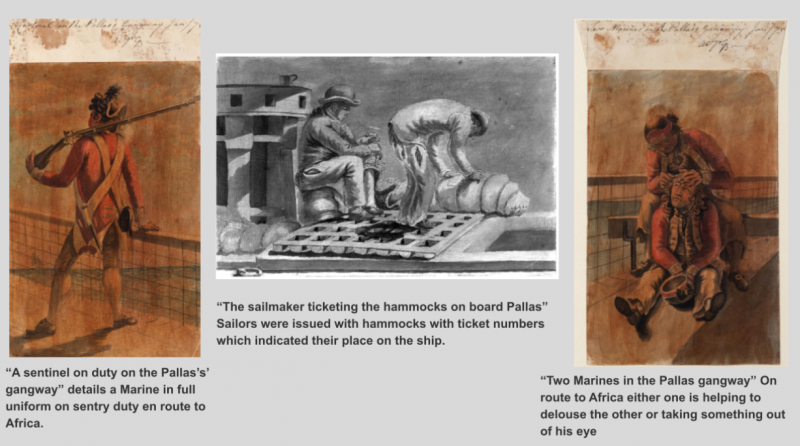

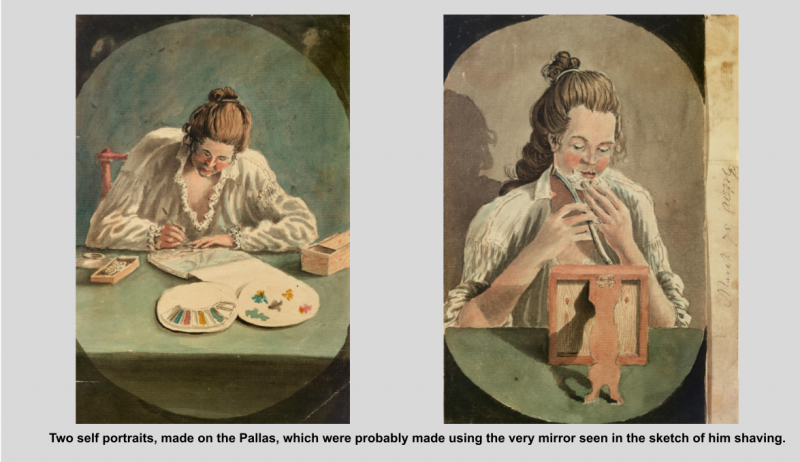

By 1775 Gabiel had returned to sea sailing on HMS Pallas to New Guinea and the West Indies. Throughout the voyage he recorded the daily life of the seamen onboard and some of the peoples he encountered when going ashore.These are amongst those paintings found in Greenwich Maritime Museum’s Collection. While Gabriel was away in the sunnier climes during the winter of 1775/76 Deal was, as was the whole of the country, in the grips of severe weather. The streets of Deal were blanketed in deep snow, where, according to Henry Stephen Chapman, the drifts were up to the first story windows of many of the houses.

Patrolling the Kentish Coast

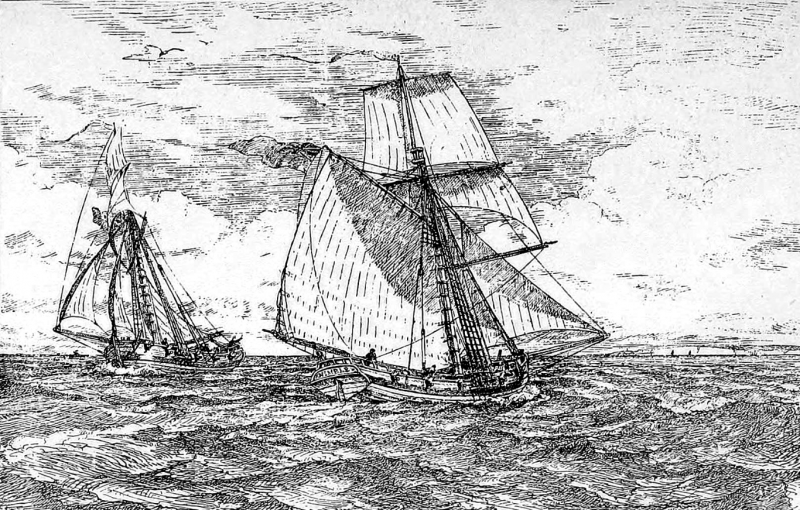

On his return to British shores, in 1778, Gabriel found himself aboard the newly built cutter, HMS Sprightly, patrolling the Kentish coast helping to defend British waters against the French. Sprightly carried 12 guns and 60 men. There are contemporary reports in the London Gazette covering the capture of French privateers by Sprightly under Gabriel’s command for which he and his crew earnt a share in the prize money.

On November 29 1780 in St. Andrew’s Church, Holborn, Gabriel married Mary Cartwright. He was thirty-one and she was just eighteen. We know nothing of how they met or about her parents, only that she had a twin sister named Ann. One of the witnesses to their marriage was Albert Innes. He appears to have acted as agent when the ’prize vessels’ were auctioned by the Admiralty and is listed as a merchant of Gould Square and Crutchfield Friars in several trade directories of the time.

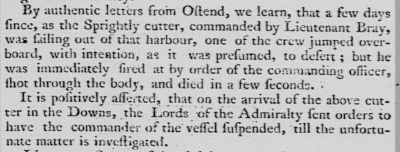

In April 1781 the violent side of Gabriel’s nature reared its head and following a rash decision he lost command of the Sprightly. While sailing out of Ostend a crewman jumped overboard- Gabriel, thinking he was deserting ordered him to be fired upon resulting in his death. On arriving in the Downs the Admiralty sent orders for Gabriel to be suspended and his command was replaced by Lieutenant Swan.

The Nimble

Gabriel was soon to find another ship. HMS Nimble was a cutter that was still under construction when the Navy Board purchased her in July 1781 from the Folkestone shipyard of Philemon Jacobs. It had originally been ordered by private owners, probably as a privateer.

After her launch at Folkestone, she was taken to the Royal Dockyard at Sheerness. Here she was coppered and fitted with guns, a single mast and rigging. She was a fairly small vessel that on completion, was 168 tons, just over 57ft long and 27ft wide. Armed with 10 x 4pdr long guns on her main deck and 12 half-pounder swivel guns dotted around her bulwarks she was to be manned by a crew of 30.

Gabriel was appointed as her Lieutenant-in-Command when she was commissioned. As the only commissioned officer aboard he would have had a Midshipman, a Warrant Officer, a Master’s Mate and a Surgeon’s Mate to assist him. While the Nimble was being fitted out Gabriel asked the Admiralty that Walter Kitchen be made surgeon and ”for a supply of Surgeon’s necessaries.” He also asks that the magazine be made tight as it is ‘severely affected by damp’.

By 1782 Nimble was sent to the Downs off Deal to patrol the English Channel, protecting British shipping against attacks by Dutch and French privateers.

The war with France was ended by the signing of the Treaty of Paris on September 3 1783 so no longer requiring a large Naval force many large and smaller vessels were sold off to the merchant service. HMS Nimble though remained in naval service and became engaged in supporting the Revenue Service in hunting down smugglers and pirates operating in British coastal waters. It is during this time that Gabriel left his mark on Deal’s history and the fight against Smuggling. That he came from Deal or that his parents and two of his surviving siblings still lived there did not deter him in any way from doing his often violent duty.

The Bray Family in Deal

Painted by Gabriel, while on Half Pay in Deal, the caption provided by the National Maritimes Museum Greenwich suggests that as “The tightly bound ‘queue’ could mean this man is an older or ex seaman and as the sketch is dated 1774 it might even be his father, John Bray. The young lady in her fashionable cap was also painted in 1774 so she could possibly be one of his sisters, Margaret or Mary.

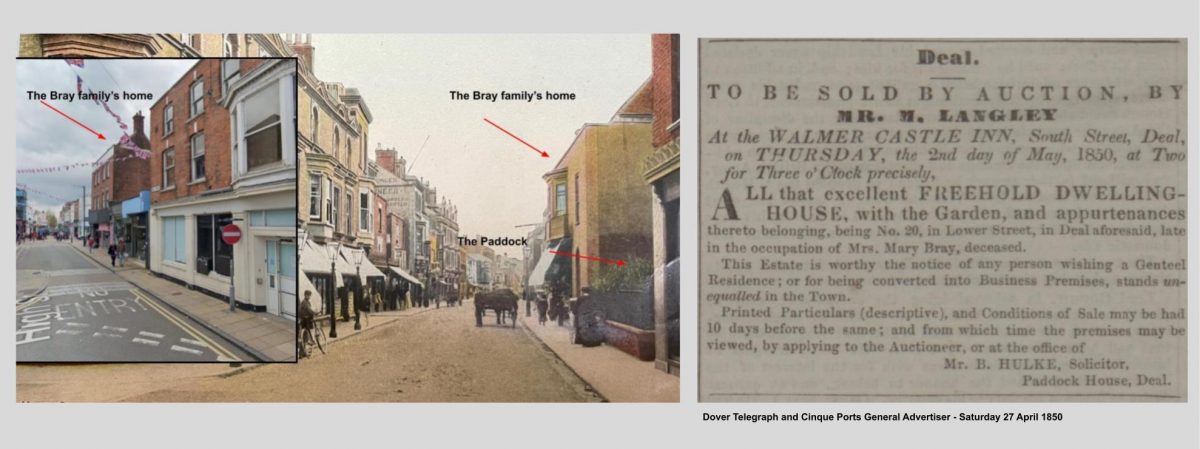

Margaret married John Coles, a Malt Factor, in January 1780 and moved away to set up home with him in Queenhithe. John Coles may have been a business acquaintance and the couple met when her father, John Bray, purchased the Manor and Malthouse in Great Mongeham in 1775. It’s not clear, but it seems that the Bray family then took up residence at the Manor from where they ran the malting business and surrounding farm land. As neither are mentioned in John Bray’s will, in 1795, the property and business must have already been signed over to John Raven at an earlier date, as it is he who continued to run the business passing it on to his daughter, Margaret, who died a spinster in 1892. John Raven himself, married widow Mary Tilt nee Wyborn in 1793 and it may have been at this time that his father, John Bray, purchased properties in Lower Street, Deal which he bequeathed to his wife and to his surviving children.

One of these houses was where Mary, his youngest daughter who never married, lived for the rest of her life. The property was right next door to The Paddock owned and occupied by the solicitor Benjamin Hulke who acted as solicitor in the sale of the house after Mary’s death in 1850. Mary must have been a friend of Reverend Montegu Pennington, nephew of Mrs Elizabeth Carter, as she presented him with a pair of silver candlesticks. She may even have been an acquaintance of the famous Blue Stocking herself, she certainly would have known about her. Deal after all was a small town.

The War Against Deal’s Smugglers

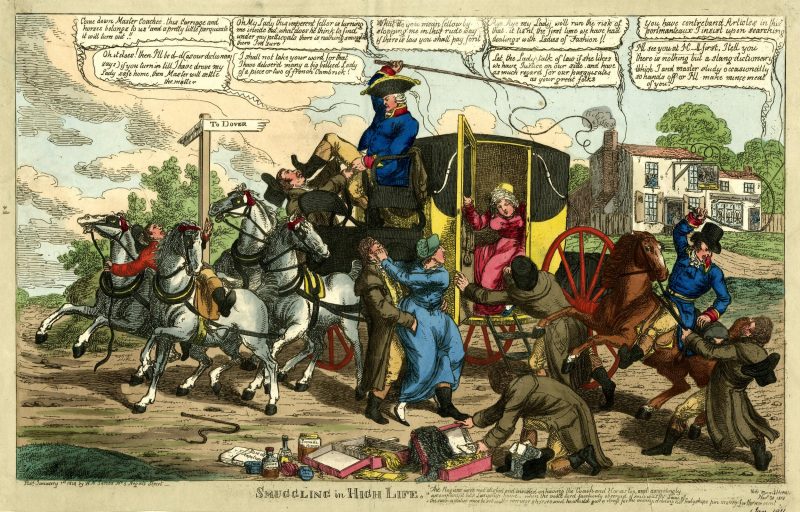

In 1784 a Parliamentary Committee Report into the ‘Illicit Practices Used in Defrauding the Revenue’ was published in which it stated that smuggling was carried out with “…enormities of such violence and extent amount to a partial state of anarchy and rebellion…” So it was into this environment that Gabriel launched into his new duties with great zeal. He later claimed, “…it was common practice for the smugglers to fire on the revenue boats; ‘they have Carriage Guns at many Avenues or Streets, to cover their large Boats, when landing Goods in the Night.” Given these two contemporary reports the description of a state of war existing between the Smugglers, operating out of Deal, the Revenue and the Navy, can not be far from the truth.

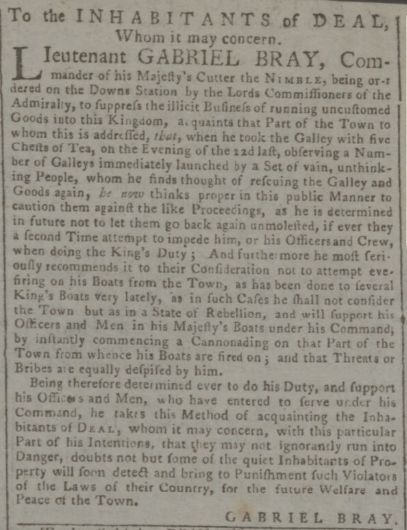

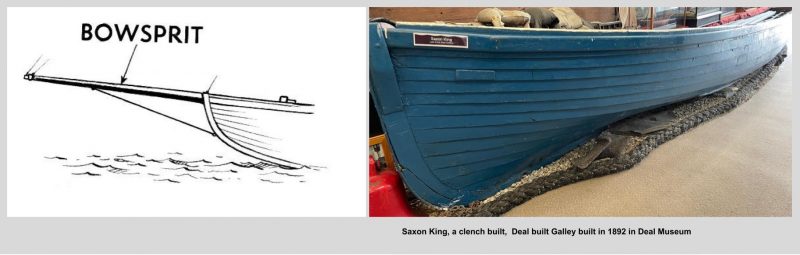

September 22 1783 was perhaps Gabriel’s first real encounter with the smugglers. While in pursuit of his duty he and his men were threatened when they captured a Galley with five chests of smuggled tea aboard, at which point a number of other Galleys were launched by, he says “ …vain, unthinking people…” to try a rescue.

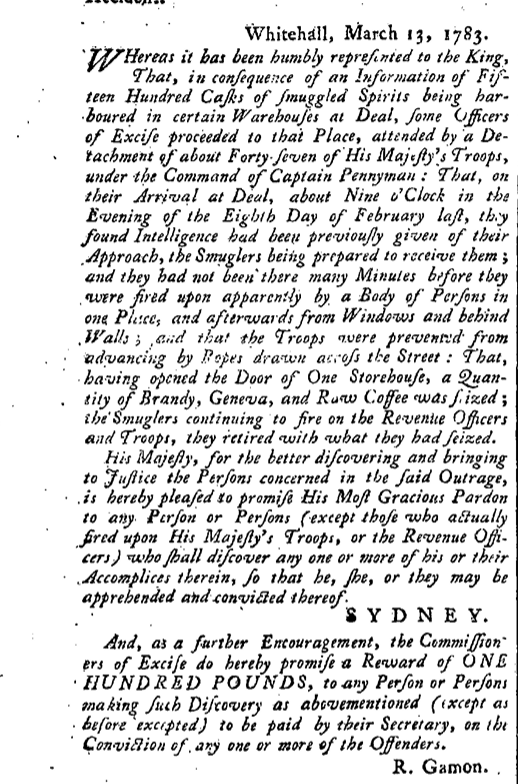

By placing a notice in the Kentish Gazette on September 27, Gabriel laid out his cards plainly on the table of Deal’s Smugglers.

He warns the town not to try such a rescue of goods again and if firing on his boats from the Town is again attempted, as had been done to several times, “…he shall not consider the Town but in a State of Rebellion, and will support his Officers and Men in his Majesty’s Boats under his Command, by instantly commencing a Cannonading on that Part of the Town from which his Boats are fired on…”

A few weeks later Elizabeth Carter wrote a letter to her friend Mrs Montagu ”… a most extraordinary advertisement lately by a commander of a revenue sloop in the Downs… The insolence of the smugglers is no doubt very great, and certainly will be while their trade is encouraged and supported by so many of those people who make laws against them; it really hurts me to see carriages of people of the first rank …leave this place loaded with smuggled goods…” she goes on to say that she had “always thought the smuggling trade a “shameful thing.”

When her nephew, Reverend Montegu Pennington edited and published his aunts letters he added a footnote to this one saying “This officer, a lieutenant in the royal navy , is still living, and being of a very respectable family, it is thought better not to mention his name” Reverend Montegu is obviously referring to Gabriel Bray. So if Elizabeth Carter knew of Gabriel, did others in the town know of him and his family- they must have done?

Contraband in the Town

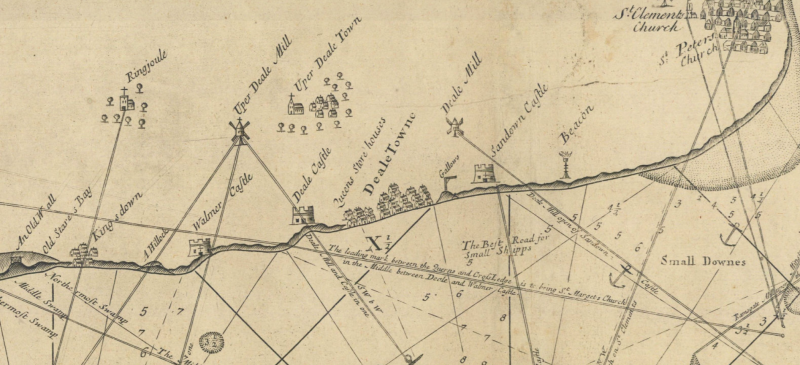

At this time the people of Deal were mainly reliant on the sea for their livelihoods. They were called upon to supply for the needs of the ships as well as the men and passengers anchored in the Downs. They also served on the coastal and cross channel vessels and on board privateers as well as acting as pilots through the straits of Dover. Most of these occupations could obviously give opportunities to smuggle or even be a cover for smuggling itself. By the 1780s the trade had reached such a proportion at Deal that it was decided by the government of the day to provide greater military and naval support to the revenue services in Deal more than anywhere else.

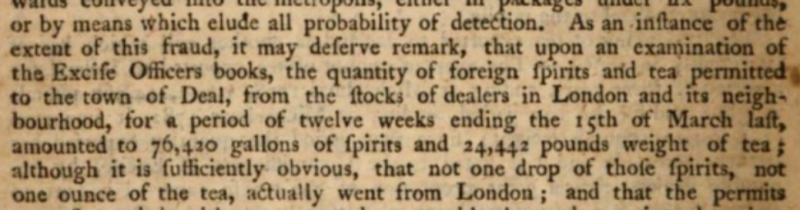

Legal imports were controlled by permits which were entered in the Excise Officers book. According to the report from the ‘Committee Appointed to Enquire into the Illicit Practices Used in Defrauding the Revenue’ printed in 1784, “…not one drop of those spirits not one ounce of the tea actually went from London…” to Deal during a twelve week period ending in March. That being 76,420 gallons of spirits and 24,442 pounds of tea. The report suggests that the permits were forwarded to Deal without the goods to enable the fraudulent import of the same amount!

Report from ‘Committee Appointed to Enquire into the Illicit Practices Used in Defrauding the Revenue’

Obviously this type of fraud wasn’t restricted to Deal but, Deal with its proximity to the French, Belgian and Dutch coasts was an ideal centre for illicit trading. Unlike other nearby coastal areas it has no cliffs, hills or other natural obstacles to impede the necessary quick access and exit from the beach. It also had warehouses and storerooms waiting to take in the undetected goods.

With information gained from informers or, even by watching out for the goods being brought in, several large scale seizures were attempted to regain the smuggled goods hidden in the town. These were violently opposed often by hundreds of armed men, and often meant the effort was not always worthwhile. The numbers of smugglers reported may have been exaggerated but it is clear that they ran the town in one way or another. Many benefited directly by the purchase of cheaper goods, from the spirits purchased by the brewers, who owned the public houses. Silks and lace benefitted the tailors, tea, coffee, sugar and tobacco the merchants, though much of what was brought in left the town spirited away to be sold elsewhere. As Elizabeth Carter wrote, visitors came to the town just to buy from the so-called ‘free traders.’ It is fair to say that the logistical organisation of such a large scale and continued illicit trade is astounding.

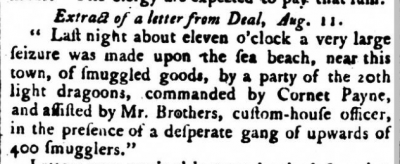

Having received information that certain persons were concealing contraband, brought in from an East Indiaman in the Downs, in October 1781 the Customs House Officers at Deal, assisted by Marines from ships in the Downs and the Middlesex Militia, entered the town. The placing of guards outside suspect houses did not go down well and those concerned, whether they were smugglers or just concealing smuggled goods, resisted violently and several were shot by the soldiers’. In this instance five wagon loads of goods were found and transported under guard first to Deal Castle then on to London. During this armed seizure the Mayor, Thomas Oakley ordered the military out of the town.

In February 1783 an extract of a letter from Deal was printed in the Kentish Gazette, telling of how sixty dragoons in searching for contraband broke open storehouses and warehouses at the north end of Deal in a “…most unjustifiable manner …” They had, according to the writer “…no warrant or legal authority for so doing…” A large body of the townsmen and the proprietors gathered together determined to stop the proceedings. Shots were fired from both sides but luckily, the writer says, no lives were lost though for a while it was feared that there would be much blood shed. The Dragoons and Excisemen though, realised that they were facing a very powerful and formidable force “…thought it proper to decamp with precipitation…”

Early in 1784 Gabriel wrote to the Admiralty, reporting how he and his crew had been subjected to “…outrageous acts of violence…” when they had attempted to land a seized Deal boat carrying contraband. He asked the Lords of the Treasury to take such measures as necessary to prevent such ‘daring and outrageous behaviour’ by the people on the shore.

Thomas Oakley, a Brewer, Maltster and, in 1784, the mayor of Deal, was the man that Gabriel apparently held responsible for much of the town’s lawlessness. Living near the beach at the north end of town he had storehouses where, according to Gabriel, the smugglers met in their hundreds. He suggested that they deposited their illicit goods in Thomas Oakley’s storehouses for safe keeping for a small fee. Their large luggers were easily drawn up on the north end beach, the only spot where this could easily be done and where Thomas Oakley had Capstans.

Here too, he said, the smugglers kept their great guns loaded, primed and ready to use and where there were large Galleys, which as Gabriel pointed out, were seizable by the Act of Parliament.

A plan held by the Kent Archives, of the Oakley holdings in North Deal, made in around 1820, show clearly the convenient capstan grounds, a Quay and the storehouses all as described by Gabriel some forty years before.

With such numbers of armed and violent men in the town it was little wonder that those local people, not directly involved in the trade, perhaps fearing a terrible retribution, simply turned a blind eye. Rudyard Kipling’s ‘The Smugglers Song’ is a romantic illustration of “not seeing” what was going on. The smugglers though, were far from romantic. They operated in gangs of hundreds of armed men who, when faced by Dragoons, and the men of the Revenue or Navy, reacted violently. You can imagine then, that in such an environment, keeping quiet was the safest option or, as Kipling says “Watch the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by.”

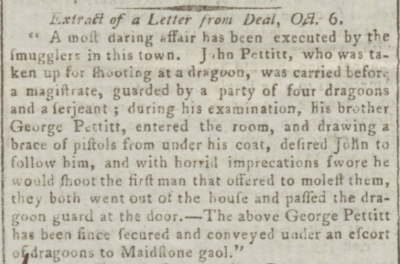

Pettitt Brother’s

In the same letter that Elizabeth Carter wrote to Mrs Montagu about the “…most extraordinary advertisement…” she also told her friend of how John Pettitt was rescued from court by his brother George and was on the run. George, though, was soon “…seized and is now in gaol, and most probably will be transported…What must those feel who bought their smuggled goods…”

What actually happened to either George or his brother John has so far eluded us.

Thomas Brown

Thomas Brown had been born in Deal in 1754 and, according to one newspaper report, he had led such a life of depredation that he was finally outlawed. We know with certainty that in early 1778 he had been detained on the charge of a “felonious offence,” the murder of a boatman of the Customs Service. Richard Baxter, with other men in service, was endeavouring to capture a large smuggling boat. In doing so they came under the fire of the smugglers, two men were wounded and Richard was killed on the spot. It’s not clear what happened next or how Thomas Brown was arrested but following his detention he was transferred via a Post -chaise, under guard of two constables, with a Mittimus (a warrant) from the Mayor of Deal to the Common Gaol at Maidstone where he was to stand trial. However, on reaching Middle Deal, several unknown persons forcibly rescued him.

A few days after his escape the Mayor & Jurats issued a notice offering a reward of five pounds to anyone who discovered his whereabouts or apprehended him in the following ten days. Thomas is then described as a “…Man of a light Complexion, and about five Feet six Inches high, and had on when rescued a Blue Seaman’s Jacket…”

By September he was still at large and His Majesty’s Government had increased the reward to two hundred pounds with a further two hundred pounds on conviction. A sum of one hundred pounds was also offered for a conviction of any of the other so far undetained offenders. Also if an offender turned Thomas in then he could expect a “gracious pardon. “

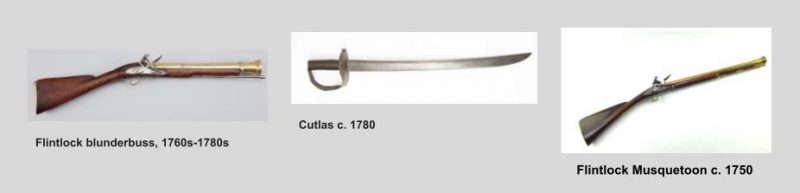

Thomas was still at large in 1784 when, on the moonlit night of April 30th, he came face to face with Lieutenant Gabriel Bray. The Nimble had been stationed off Deal on the lookout for Smugglers when they spotted a vessel which at some distance appeared to be a lugger. Gabriels testimony states that he immediately ordered his men on deck and manned two boats in order to discover the business of the vessel. In turn, the men on the vessel, that turned out to the lugger Juliet, enquired after Gabriel’s business. On declaring who he was and that he belonged to the Navy cutter Nimble, he was sworn at in a violent manner and was immediately fired upon. One shot hit John McNeer in the chest, a wound from which he immediately died.

With several of his men Gabriel then boarded the lugger and a violent skirmish took place. According to the Oxford Journal who printed an “extract of a letter from Deal May 2” on boarding the Juliet, a smuggler identified as Thomas Brown, presented a Blunderbuss. While standing his ground one of his men, armed with his cutlass, cut Thomas’s cheek clean off. Gabriel then, with his own cutlass, almost severed Thomas’s head from his body.

This last fact may not be exactly true. Nathaniel Rammel, the Sexton of St. George’s Church, Deal, kept a record of the graves he dug and under Thomas’s name he wrote “shot by Bray”

Thomas was not the only fatality that evening. The Nimble lost John McNeer, and another was wounded. Of the crew of the smuggling vessel under Thomas Brown, there were three killed, two wounded and a further two taken prisoner. Four hundred casks of illicit spirits were also recovered that night.

Samuel Harris and John North

In June 1784 the two prisoners captured that night were committed for trial and imprisoned at St. Dunstan’s gaol Canterbury. Samuel Harris and John North were both charged with the murder of John McNeer and by the middle of August they found themselves in Newgate prison, with their trial taking place at The Old Bailey on November 10th that year.

Evidence given in court told of how they had tried to pretend to be passengers but when searched their pockets were full of musket balls and cartridges and of how John North had, at some point, taken the opportunity of jumping overboard with the aim of swimming ashore but was soon captured. Gabriel stated that “there could be no doubt that they fired the shot as there were but eight people onboard and five pieces (blunderbusses and musquetoons) were seen to go off and two or three others flashed in the pan.” This was all corroborated by James Laney, Thomas Grant and Dennis Hennesy of the Nimble. The surgeon Mr. John Russel confirmed the manner of John McNeer’s death. He was buried in St. Mary’s Church Dover on May 5th.

In the defence of Samuel Harris, his counsel Mr. Garrow told the court that there was actually no evidence to prove that he had shot John McNeer. The Attorney General remarked “… that where a number of people were assembled together in an unlawful manner, and murder ensued, it was not necessary to ascertain the exact person who fired the piece, for the act of one man, was the act of the whole, and all were equally guilty…” Two witnesses to his character stated that while working at several public houses and the Assembly Rooms in Margate, he appeared to be of excellent and honest nature. In court he is described as about thirty years of age and genteely dressed.

In the defence of John North a former employer said he was a man averse to fighting, and was in fact rather a coward. Described as rather small and about twenty five years old he behaved extremely decently.

After just ten minutes of deliberations the jury brought in a verdict of guilty and the two men were sentenced to death. At nine o’clock on the morning of Saturday 13 November Samuel Harris and John North, under the guard of officers from the Admiralty, were taken from their cell, put in a cart and conveyed to the gallows at Execution Dock. Several newspapers report that their dead bodies were then taken to Deal to be hung in chains, others, including the Kentish Gazette state that the Government had ordered that their bodies were to be anatomised and the body parts to be hung in conspicuous parts of Kent & Essex. Either way their bodies, as had happened to many others before them and continued to do so until around 1830, were to be used as macabre warning to others who may pursue such activities.

Juliet, the lugger on which they had been captured was also condemned. Then, as the two hundred pounds reward money was offered for information leading to Thomas Brown’s arrest, it was agreed by the authorities to give that to Gabriel and his men as a sort of incentive bonus! In today’s money that is approximately just over seventeen thousand pounds.

In September 1784 Gabriel asked the Admiralty if he could appoint John Lambert as the ship’s cook “…as he had been injured in a fight with smugglers at Deal…” Given the date it may well have been during this same skirmish. Then when the Nimble is paid off to be refitted in 1786, Gabriel again writes in support of John Lambert who he says lost an arm while serving with him. “..He is a young man and asks for a position to be found for him…”.

In early August 1784 the London Gazette printed a Proclamation from the King concerning two incidents at Deal. The first occurred on July 16 when, we are told, a great number of “disorderly persons”, armed with firearms had assembled at the North End of Deal to “… forcibly obstruct and fire upon the crews of the boats acting under the orders of Lieutenant Bray, who was in pursuit of a six oar galley contrary to the statute…” Then on August 2 another great number of armed persons assembled at Deal. This time to obstruct the Officers and men of the boats belonging to the ship Scout who were acting under the orders of Captain Lindsay, Gabriel’s commanding officer, who were trying to seize a lugger suspected of carrying illicit goods. During this action seaman William Russell, belonging to the Scout, was shot.

The proclamation strictly charged and commanded all Magistrates and other Civil Officers and “Our Subjects” to assist to their utmost power in “..suppressing such illegal and tumultuous Assemblies…” A reward of two hundred pounds was offered for each offender so discovered and convicted.

The sailors on vessels in support of the revenue took their lives in their hands when visiting the town. In that same August a man was attacked and beaten outside the post office when he was recognised as a midshipman from the Nimble. The post office was probably in what today is called Kings Street but then Whetstone Street, named after Nicholas Whetstone an early postmaster. Those suspected of informing against the smugglers were even more also harshly treated. One suspected informer, a man named Francis Folkes, who we’ve not been able to identify was beaten to death in 1784.

Legislation Against Smugglers Boats

With the increasing size of smuggling vessels the Hovering Act was updated in 1779 so that any ship under 200 tons, caught bringing contraband into any British port, or hovering within two leagues (six miles) off the coast, was liable to forfeiture, along with its guns, ‘furniture, tackle and apparel’. By 1787 the act had amended the jurisdiction to four leagues.

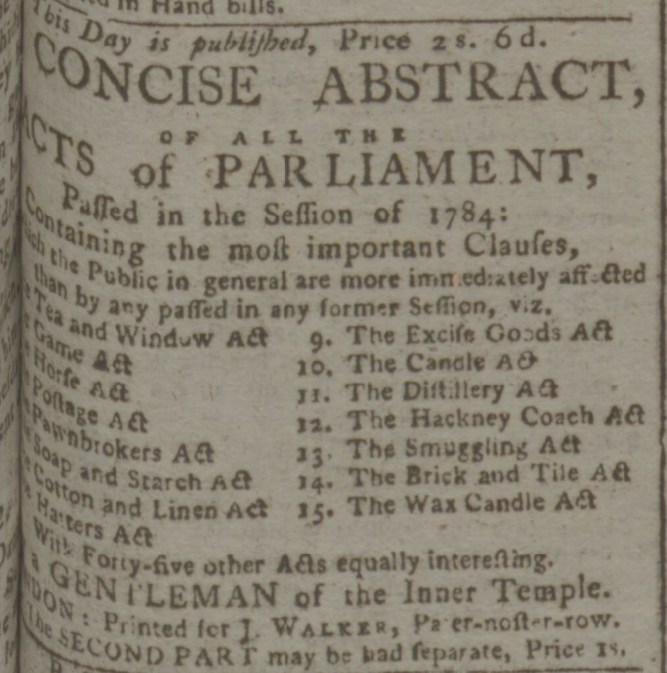

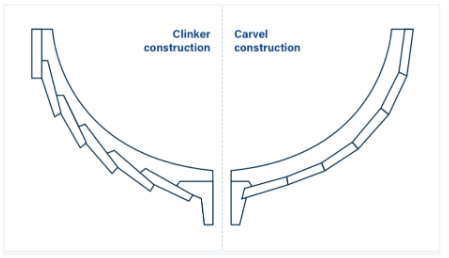

In October 1784 The Smuggling Act was passed in an attempt to further impede the smugglers whose vessels were built for speed. From the 1st of October 1784 the size of vessels built to row with more than four or six oars could no longer be more than 28 feet in length. Clench built vessels such as cutters and luggers, and those fitted with a running bowsprit were also banned and any person caught shooting at a Naval vessel or its crew or the Customs & Excise officers faced the death penalty. Those who made a ‘legal’ living from the sea, such as fishermen, had their livelihoods looked after and those with clench built boats were required to licence their vessels.

The Burning of the Boats

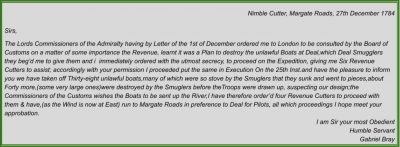

So it was in November 1784 that the Treasury were informed that a great number of unlicensed, so ‘illegal’, clench built boats were still in use at Deal. The intelligence came from the Customs Commissioner of Sandwich who claimed that there were approximately 80 clench built vessels from thirty to fifty feet in length “…all kept in private places with the greatest of care…” Obviously this could not be ignored. Gabriel received a letter to report to the Board of Customs in London at the beginning of December where he learnt of the Plan to destroy the unlawful Boats at Deal.

Captain Lindsey wrote in his log for the 26 December that he had assisted in the removal of the boats from the beach and sailed with them the next day. This corroborates Gabriel’s own account in a letter, sent to the Admiralty, written aboard the Nimble two days after the action.

It was on January 10 1785, so just over two weeks later, that The Times printed their version of the events and, as we have already said, it was not printed in the Kentish Gazette. Seventy three vessels on fire would have been a sight and the smoke billowing up from them would have been seen for many miles around; the fact that it happened on Christmas Day too would, you would have thought, have been remarked upon in the the counties newspaper but there is a stony silence, not even the actual seizure itself is mentioned. For such a momentous action this seems rather strange. Even Mr Pitt sending to the War Office requiring a regiment of soldiers to be sent to Deal on a certain day is questionable. According to research carried out by P. Muskett, there is no trace of any such a request being made. Supposedly too, there were no quarters for the soldiers in Deal, yet accommodation for soldiers would have been arranged as soon as any decision was made to send them anywhere.

Seizures at other nearby ports were to have taken place but word had got out and the ‘illegal’ boats were spirited away. On the 27th December 1784, a Hastings boat owner, George Wood, while trying to prevent his boat from being seized was shot dead by dragoons. The dragoons were tried and a verdict of wilful murder was given. It may be just coincidence, but following this incident and the earlier failures no more large scale seizures of vessels seem to have been attempted.

Perhaps then, the very fact of Deal being the only place reported to have had such a large action taken against it has, in itself, routed the story in peoples collective memories.

With the benefit of hindsight the solution to smuggling was to cut the duties levied on the goods that were being smuggled to a level where it was no longer profitable to do so. William Pitt (the younger) saw this but proceeded slowly. The Commutation Act of 1784, created to stimulate trade with China for the British East India Company, reduced the duty on tea from 119% to 12.5% so ended the profitable smuggling of tea. In 1786 a trade treaty with France, halved the duty on wines. More reductions followed but it only produced a lull. Smugglers soon found other avenues to follow and Deal continued to be in the forefront of smuggling.

Later Gabriel was recognised for the “…important service rendered by him to the Revenue…” by the Commissioners of his Majesty’s Customs who presented him with a silver cup engraved with For Mr Gabriel Bray Commander of the Nimble Admiralty Cutter. Presented by order of the Commissioners of his Majesty’s Customs in testimony of their approbation of an important service rendered by him to the Revenue under their management on 25 December 1784. It is now in Liverpool Museum

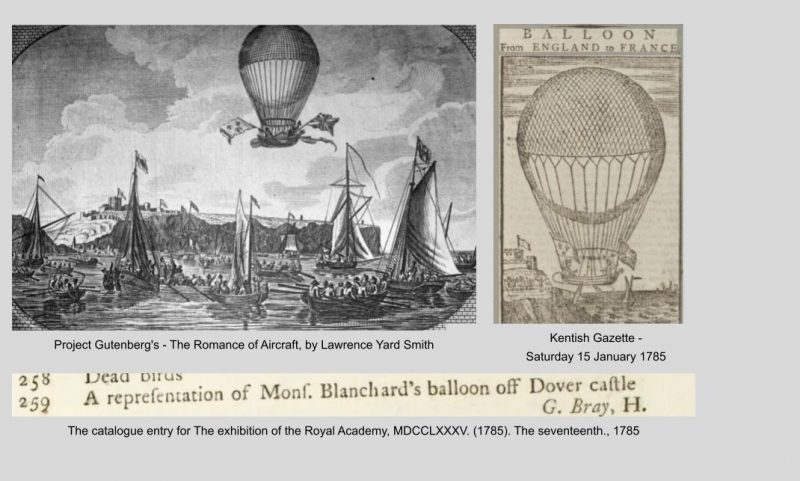

Blanchard’s Balloon

Three days before The Times story broke Gabriel witnessed the first successful balloon flight across the channel on 7 January 1785. Taking off from near Dover Castle at 1 pm the balloon had taken nearly four hours to fill with hydrogen. The gas entered the balloon via tin pipes. The balloon secured to a boat, in which Blanchard and his passenger John Jefffries sat, by ropes or cords. The highly flammable hydrogen was made by pouring hydrochloric acid onto iron but how that was captured is not clear.

Flying from either end of the boat were the Union Flag and the Royal Standard of France.

It was reported that a King’s Cutter brought the news back to England, that at ten minutes past three the balloon had landed near Calais. Even if this wasn’t the Nimble Gabriel painted the scene and entered it into the Exhibition of the Royal Academy later that year. The catalogue shows that he was by then an Honorary Member of the Academy. This painting is one that is hopefully in private hands but representations, by others, survive.

Attacks in Deal

Throughout the rest of 1785 and 1786 there are no reported clashes between Gabriel or the men of the Nimble and the Deal Smugglers. Perhaps then the seizing of the boats did have some short term effect. We know from The National Archives records that Nimble was still at its station patrolling off the Kentish coast. In July 1785 Gabriel requested a cable from Mr. Lawrence at the Naval Yard in Deal and in January 1786 the Nimble lost one of its boats, preventing it from taking on fresh water so a request was made to the Admiralty. And between October 1786 and June 1787 Nimble underwent repairs at Sheerness.

Soldiers, Officers of the Customs, the Revenue and informers continued to be attacked in the streets of Deal and rewards offered for convictions but with what success we don’t know.

March 1785 a soldier, of the 43rd Regiment of foot stationed at Deal, was assaulted and “…inhumanely hamstrung by several persons…” on the suspicion of being the informer whose information led to the seizure of contraband.

September 1786 the 63rd regiment of Foot was supporting the Customs. One evening when three of their soldiers were returning to barracks they were fired upon and one was hit in the knee. A reward of one hundred pounds was offered for the culprits’ apprehension and conviction.

May 1787 Boatmen of the Customs were attacked at the North End by a gang of smugglers with Bludgeons. A Reward of Fifty Pounds was offered for the offender’s conviction.

What is clear from ours, and others research, is that Deal before, during, and after Gabriel’s time was a violent, almost lawless place to live and where the smuggler had the upper hand.

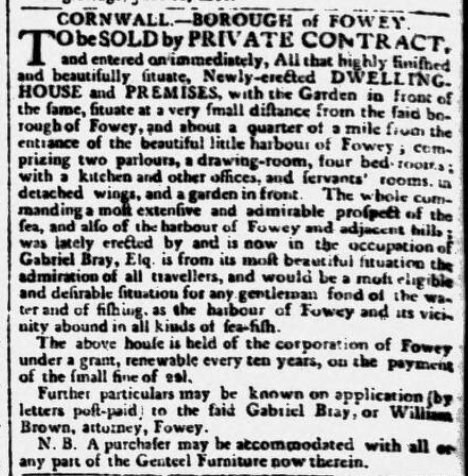

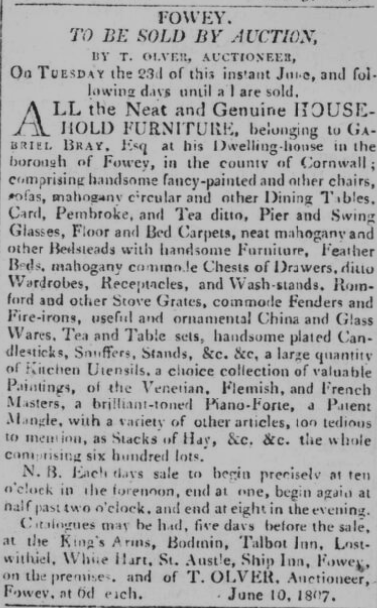

We have just concentrated on Gabriel’s time in Deal and the Downs and in particular his fight with the smugglers which continued for the rest of his Naval career. In 1786 Captain Dobbin succeeded Gabriel as Commander of the Nimble. By 1787 Gabriel had transferred to the Revenue service and moved from the Kentish Coast to Lymington in Hampshire before moving to Fowey in Cornwall where he commanded the Revenue Cutter The Hind with many more incidents against Cornish Smugglers are recorded.

In 1800 Gabriel’s health had declined so aged fifty he retired from the service and it was then that he put his house up for sale and left Fowey, the place he and his wife Mary had called home for ten years, though it seems the property did not actually sell until after 1807.

They then spent a number of years in Newington, London, then a little while in Hythe, Kent where the Bray family had property, before eventually purchasing a house in Charmouth and it was here that they spent their remaining days. Gabriel died in 1823 and is buried in St. Andrew’s church where he also served as churchwarden; Mary outlived him by twelve years, dying in 1835. The couple did not have any children so in her will Mary left all her Deal holdings, inherited from her husband, to Gabriel’s niece Margaret Bray of Mongeham and to his sister Mary Bray who was still living on Lower Street in Deal.