Follow us on Facebook @FHofDW

John Moss

Backway of the Strand, Walmer

5 Wellington Place, Middle Road , Walmer

67, York Road, Walmer

Occupation: Mariner, Coasting Pilot

John Stephen Moss was born in Walmer in 1834. He spent his whole adult life making a living from the sea. Aged nineteen he joined the Navy and from a transcript of his service record we know what he was 5ft 4 1/2 inches tall , had a sallow complexion, grey eyes and light coloured hair and that at some point in childhood he had contracted Smallpox which had left his skin pitted with scars.

He had joined the navy in the early 1850s , serving on HMS Tortoise, Magpie and Scourge. His conduct was reported as ‘Good’ throughout the whole of his service which he left in May 1856. A year later on 22 September 1857 John married Martha Ann Atkins at St. Mary’s Church, Walmer by which time he had joined the ranks of Deal & Walmer boatmen who acted as pilots. These often ill educated men had no certificates to prove their capabilities but a simple system of testimonials written by the ship’s Captains was used instead.

Testimonials or Letters of Recommendation

In Deal Museum Archives there are several transcripts of testimonials given to John by the Captains of the vessels he had piloted.

There is also a transcript of a letter from John himself. This was sent to Messrs Crosby of Liverpool, who may have been agents or solicitors acting on behalf of the widow of a Captain Barrett . Early in March 1887 John had acted as pilot onboard the Craigburn and he says

“While off Folkestone Captain Barrett went ashore to buy some provisions…” and “..to cover the cost of and as to the expenses of boat hire. Captain B. not wishing to draw on his owners, borrowed the money from me viz £8 5s promising to repay me on arrival at Dundee…”

which he didn’t. John had already written to Greenock, the ship’s owners, explaining this matter but they, he said “… inclined to recognise it…”, he went on “…I am prompted to beg your kind help in this unpleasant matter as I am only a very poor man and the loss of so much money is a very hard trial for me through having obliged her late husband…”

Captain Barret had written to John on the 23rd of March promising repayment as soon as possible “…but I am, he says, in great trouble as regards North Shields…”

What was meant by this we don’t know. But two days later he shot himself onboard the Craigburn in Dundee Harbour. Captain Barrett was certainly deeply troubled by something.–He had already on this voyage home tried to poison and shoot himself. The death of a crew member who fell 100ft to the deck -when the ship arrived in Dundee could not have helped with his state of mind.

Did John get his money back ? Well we don’t know but if you think that in 1886 the average earnings made by John’s lugger was £13 from which he had to pay the crew and maintain the boat, £8 was then, a lot to be lost.

A Brave Man

John, it seems then, was an honest, efficient and likable man.

We also know him to have been a selfless and brave one too.

Some thirty years before in December 1858 John was out in the Lugger Stronaway. He, with three other crew members, had just shipped a fellow crew member onboard a vessel to pilot it through the channel. A strong breeze was blowing and a heavy sea was running and the punt they were in got under the bow of the Stronaway and was run down, surfacing bottom up. The punts crew, William Axon, George Claringbold and John were, the newspaper reported in the wonderfully descriptive language of the time, “precipitated into the water”

The report goes on to say that a bobstay, which is a rope to you and me, was thrown from the Stronaway and John managed to grab it and haul himself up. Once on board he expected to see the others following him. William Axon though was struggling, his rheumatism and the time in the cold water of the channel – remember this is mid December- had weakened him leaving him unable to save himself. John realising his friend was in trouble risked his own life by jumping overboard, on reaching William he lashed the rope around him and with the assistance of the luggers crew, got him on board saving him from “a watery grave”.

They then looked around for George Claringbold. He had surfaced near the upturned punt which he had scrambled onto and was hanging on for dear life. He now though was some distance off, and after several attempts at getting the lugger close to him, John, once again, jumped overboard.

The bobstay was again thrown and John, holding on to George, managed to get them both to it. George by this time was frozen, exhausted and beyond helping himself. Later John was to say that he had “ …he cheered him on in every way he could but he made no reply!…” A heavy sea then washed them both off the rope. Managing to grab hold again John started to swim towards his friend who had been washed further away but “…before he could get to him, he sank and was not seen again…”

George left a widow but no children.

Medals for Bravery

John was quite rightly praised and this made its way into the newspapers which spoke of John’s “extraordinary exertions in defiance of the boisterous weather” and that he was “entitled to the highest praise as an instance of extraordinary perseverance under circumstances of the most appalling character”

For his bravery John was awarded a silver medal from the Shipwrecked Fishermen and Mariners Benevolent Society and the RNLI silver medal and clasp. These were presented to him in Walmer Infant School Hall, where a letter was also read from the Royal Humane Society announcing that their silver medal would also be awarded. John, we are told, accepted all this in a most unassuming and respectful manner. What he was really thinking we obviously don’t know, but not being able to save George Claringbold must have played on his mind and it may have been some small consolation that a collection was started that evening for his widow.

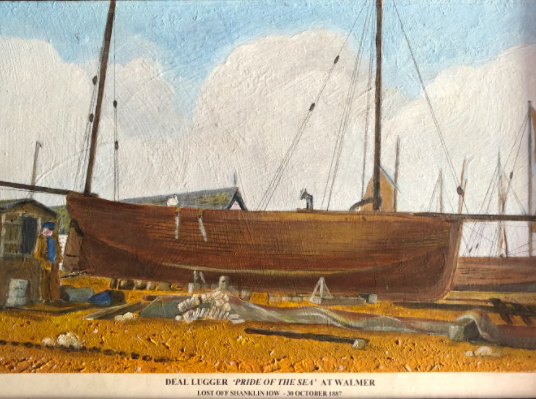

Pride of the Sea

You may have read of of the loss of Pride of the Sea here on the website which was owned by John Moss and his brother William.

William was married to Hannah, nee Tapley. You may also have heard of Tommy Adams as the only survivor who knew nothing of the tragedy until he arrived home after Piloting a vessel to Dunkirk. In the book Last of the luggers Tommy is quoted as saying that he had never sailed with “…a pleasanter boats crew …” and in all the time he had been one of the crew he never heard an angry or unkind or unpleasant word on board.

Given that half the crew were related it suggests that they, as a family, got on well together and this must have helped create the pleasant working atmosphere that Tommy described. A blessing when working in confined and sometimes dangerous situations.

John and William not only worked together they lived almost as neighbours near on York Street, Walmer and in the mid 1870s they jointly took out a loan to purchase their Pride of the Sea.The transcript of the earnings book shows that they worked hard and they had only just cleared the debt when they, their nephew Charles Moss and two other crew members, lost their lives in the storm that wrecked their vessel.

On the morning of October 30th, after spending twenty days at sea and only boarding one pilot, Thomas Adams, they were caught in a severe South Easterly Gale, Pride of the Sea was driven ashore at Shanklin, Isle of Wight.

The first indication of the tragedy was the washing ashore of a punt later followed by the wrecked Pride of the Sea. As soon as they could, locals boarded the vessel to find clothing in bundles, some in bags and other belongings strewn on the floor indicating that the crew had left in some haste.

It seems that realising the Lugger was sinking they had rushed to gather what belongings they could hoping to get in the punt. But the situation changed quickly and what happened after that led to all the men losing their lives.

John’s body was the first to be washed ashore. The inquest into his death was held on Monday 31st at the coincidentally named Sandown Castle near Shanklin. John Stephen Moss, John’s eldest son, travelled by sea to Shanklin and identified his fathers body.

The surgeon had examined John’s body the day before and his report was read out to the jury, he concluded that ‘ death was by drowning’. In summing up the coroner said that he felt that he did not suppose anyone had the slightest doubt that the man had met his death accidentally through the storm. And this verdict was duly passed.

There was to be no insurance payout for the wives of John or William; the premiums for owners like themselves were just too prohibitive.

To give the families some relief, subscriptions were set up and collections were made in Shanklin, where the men were fairly well known, as well as in Deal and Walmer. Just over £363 was collected and equally divided between the families of the lost men.

John Moss , William Moss, Charles Moss, Henry Kirkaldie and Charles Selth were buried together in the cemetery at Shanklin.

A fund was set up in December 1887 to purchase a Memorial Stone for the men that was approved by the Shanklin Burial Board in late May 1888 when it was described as a marble cross on boulders, with an anchor and an inscription. Martha, John’s wife, visited the memorial when it was erected.

The memorial over the decades suffered badly from weathering. In 2002 descendants of the Moss family paid to have the Memorial restored.