Follow us on Facebook @FHofDW

Stephen Crambrook

The Peninsular War and The Battle of Waterloo

Kingsdown

Lower Street, Deal

Hyde Park Barracks, London

1 Trevor Place, Knightsbridge

Occupation: Watchmaker, Private 15th Dragoons, 1st Life Guards

The Crambrook Family

After researching Henry de Humboldt, who served in the King’s German Legion and fought at the Battle of Waterloo, we wondered how many men from Deal would have also been there. With few military records giving details of place of birth during this time we have, so far, found only one.

Stephen Crambrook was born in Ringwould the son of watchmaker, John Crambrook and his wife Elizabeth. He was baptised in the parish church of St. Nicholas in 1784. In 1786, when Stephen was two years old, his eldest brother John married and in the same year ‘settled’ in Deal. Another brother Richard also settled in the town four years later and, at some point, their father moved into Deal with his wife, Stephen and his siblings.

Although no apprentice records have been found for any of the Crambrook brothers, other records tell us that John was a Linen Draper and Richard a Victualler. As Stephen became a Watchmaker it seems fair to assume that he learnt his trade in the workshop of his father or of his uncle and namesake in Dover.

Cinque Ports Volunteers

Under the threat of a French invasion, in 1803, two Acts of Parliament were passed to raise men for the purpose of home defence; the Army Reserve and the Levee en-Masse. These are also known as the Lieutenancy Papers, in which Stephen and his brothers John and Richard are recorded. Both John and Richard appear to be exempt from serving. John as he was lame and as Richard died in July 1804 it is possible he was too ill to serve. Stephen was listed as an ‘inmate,’ meaning he was living at home with no dependents. He was also listed as a volunteer in ‘Mr King’s Company.’

It’s not entirely certain who this Mr King was but he did become a Captain of the 2nd Battalion of the Cinque Ports Volunteers whose Lieutenant Colonel, Lord Carrington, was also Captain of Deal Castle.

A recruiting party, including infantry and light dragoons, drinking and smoking in a tavern, 1805 A E Eglington National Army Museum

In May 1803 a Deal Ropemaker, named Joseph King, appealed to George Irwin the Regulating Officer to release his Apprentice William Cleaveland who had been impressed. So it is possible that he is ‘Mr. King’

Enlistment

Despite the Army always struggling to fill its ranks, conscription was not used until WW1. Therefore, recruiting parties were sent out into towns and cities, often using underhand methods to ‘persuade’ men to enlist. As the men of the militia had some training, they were an obvious, ready-made pool from which to recruit, and this gives us a probable reason as to how Stephen joined the army. As to why a young watchmaker from Deal wanted to join we obviously don’t know with certainty. Maybe he enjoyed his militia experience or that he, as with so many other young men, simply needed to support himself.

The term of army enlistment when he joined was ‘life’; however in 1806, a system of ‘limited service’ of seven years for infantry, and ten for cavalry and artillery, was introduced to attract more recruits.

Once enlisted, he would have received a bounty which, as Stephen joined a cavalry regiment, it would have been around £23. This sounds like a lot, especially when you realise that it was around six months’ wages for an unskilled worker of the time. Much, though, would have been eaten up by the cost of uniform and other requirements. As well as his initial wage of 2s per day, Stephen would also have received a daily beer money allowance.

It seems, though it’s not very clear, that Stephen initially enlisted in the 15th Dragoons, sometime after the Levee en-Masse was taken in July 1803. Then on December 20, 1805, he joined the 1st Life Guards. We don’t know why he transferred to the to the Life Guards; he may simply have he caught the eye of the officers of the 1st Life Guards; Dragoons at the time had a minimum height restriction of 5ft 4inches and Stephen would have stood out at 6ft 3inches tall.

Traditionally the Life Guards role was to protect the sovereign and police London, so whatever the reason for Stephen’s transfer he may have considered himself lucky to be in a regiment who rarely saw foreign service.

Life Guards

The 1st and 2nd Life Guard regiments each consisted of 5 troops, a Captain, a Lieutenant, a Cornet, a Quarter Master and three companies of 50 men.

In 1812 the Prince Regent ordered a uniform change and the cocked hats were replaced with brass helmets with a black hair crest. Their long red coats were replaced with short ‘coatees’ with sashes of gold for officers and blue and yellow for the men. For royal escort duties they wore leather pantaloons or trousers with jack-boots. For all other duties grey trousers with a red stripe and short boots.

They were also issued with short carbines with bayonets, a sword and a pistol and white gauntlets and breastplates.

Two years later the horsehair mane was changed to a woollen crest which was coloured dark blue over red. This was the helmet worn at Waterloo.

The Life Guards, since their formation in 1788, have been known for their large black horses. As the regiment that protected the sovereign and took part in ceremonial events, these men had to not only look good but live up to the occasion too. They had the advantage, not available to others, as the only two regimental riding schools in England, at the time, were reserved for the Life and Horse Guards.

Marriage

In May 1807, Stephen’s father died, leaving a lengthy will with most of his assets divided between his nine surviving children. This legacy may have placed Stephen in a reasonable financial position to marry Elizabeth Piddock, who probably also came from Deal. The marriage took place in St. Marylebone Church, Westminster, at the end of 1807. With no married quarters at this time, Elizabeth may have either found work and lodgings near her new husband’s Barracks, at Hyde Park, or returned home to her parents. Whatever the case, they did not have their first child until 1816. With the growth of unrest across the country including in the capital Stephen may well have felt it was safer for Elizabeth to be at home in Deal.

1810 London Riots

The early 1800s saw a period of economic hardship, social unrest and the rise of calls for Parliamentary Reform. In early 1810 the radical John Gale Jones was committed to Newgate Prison by parliament for provocative agitation against the government. The Whig MP Sir Francis Burdett, who was one of the early proponents for parliamentary Reform, questioned parliament’s right to do this and sought his release. After William Cobbit printed a version of Francis Burdett’s speech in his ‘Weekly Register’ the Speaker of the House of Commons issued a warrant for Sir Francis’s arrest. On hearing this he barricaded himself inside his London home while mobs gathered outside in his support.

A letter from Private Henry Willis, who was also in the 1st Life Guards, written to his sister describes the events that followed. He wrote “…On the Friday 6th instant in the evening, the people began to assemble in the streets, the general cry was Burdett for Ever…” he goes on to say how they were ordered out to disperse the mob on that Friday and on the following day. When the Riot Act was read they were fired upon and several Life Guards were injured. The unrest continued into Sunday evening when they were reinforced by Regiments of Dragoon. “…On Monday morning the Sergeant at Arms ordered Sir F. Burdetts house to be forced open, accordingly it was done…” Sir Francis was then escorted to the Tower of London in a coach with the mob surrounding them all the way. Private Willis ends his letter by asking his sister not to say this information came from a soldier as it was against orders to write about it he ends ”…I am afraid things are in a very dangerous state at present…”

Stephen may well have known Henry Willis, as both were Privates in the 1st Life Guards. This ‘action’ in 1810 may also have been the first time they experienced a ‘hostile’ foe. They would soon be faced by a much greater and dangerous foe.

The Peninsular Campaign

Another letter from Henry Willis dated October 19, 1812 was written just before the regiment embarked for the Peninsular Campaign. He wrote that they had been in an “…unsettled state about the regiment going abroad, but it is finally determined. We march off to Portsmouth this morning…” They arrived at Portsmouth on the 24th and from there sailed for Lisbon. Their voyage was a rough one which Henry expected “…every minute to be our last…” On disembarking they marched on to Belem from where he wrote to his sister telling her of the availability of fruit, wine, rum and brandy and their cheapness. However there were no butcher’s shops and beef and mutton was scarce and bread and potatoes very expensive. “…I have not seen a bed since we left England nor do I expect to see one until I return, if ever I do…” he writes “… We have one blanket and our great coat to lay upon…” Sadly Henry did not return home, he died of sepsis after a fall which broke his leg in 1813.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

While serving in the Peninsula Wars Stephen suffered from an ‘illness,’ but exactly what is not recorded. Diseases that can so easily be treated today, then often led to serious, debilitating, and even life-threatening conditions. With hundreds of men living together in unsanitary conditions with poor food and perhaps drinking and bathing in contaminated water, it was no wonder so many soldiers died from disease.

On his return to Britain in 1815, Military Surgeon and Director of The Army Medical Board, Sir James MacGrigor, published the observations he made during the Peninsula campaigns. He describes the diseases, how they affected the men, and their outcomes. He also recognised that even if men were not suffering from disease, a change in climate affected their general health, stating, “…that troops coming to a climate different from their own should be somewhat habituated to it before they enter on the fatigues of the service…”

Stephen was it appears from his Statement of Service, one of the many whose general health was affected by the climate and even from an unrecognised, or more likely an unrecorded, illness or injury during the two years between 1812 and 1814 when he was serving in the Peninsula.

.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

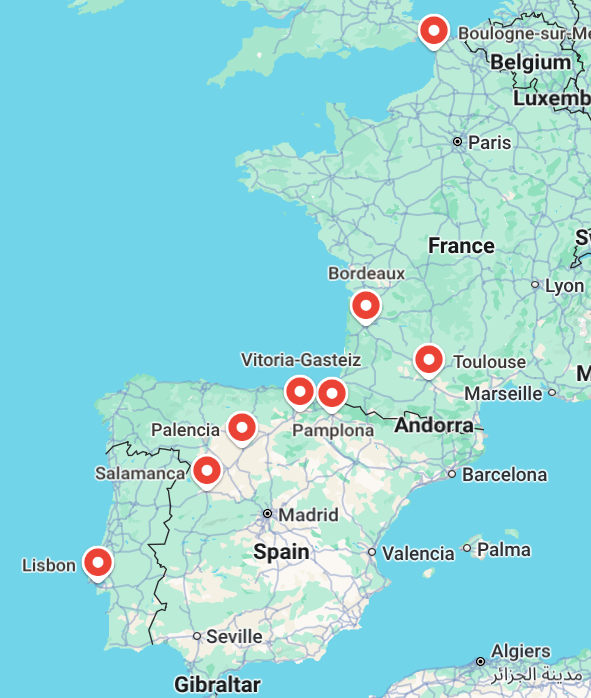

In early 1813 the Life Guards marched to join Wellington’s army as they advanced into Spain. The allies had gained Salamanca on 26th May. The next day the 1st Life Guards stationed themselves in the monastery; a few days later they marched on and, as the enemy withdrew to Madrid, they crossed the River Carrion at Palencia. Wellington then moved his army through rugged and narrow passes and mountainous terrain heading for Vitoria. The enemy made several attacks but they were repulsed and soon retreated. The two Life Guards regiments took no part in these actions but they shared the privations and exhaustion caused by the hastily called long marches across difficult rocky terrain and along narrow tracks where the men marched in single file leading their horses. On reaching Vitoria the regiment took part in the ensuing battle, Stephen was amongst them.

Victorious they marched onto Pamplona where they camped for the night in a wood, in pouring rain and no provisions. Pamplona itself was besieged from June 26 until October 31, 1813 but the 1st Life Guards took no part in this as they had moved on. The final battle of the Peninsula Wars which they took part in was in France, at Toulouse on April 10, 1814, after which Napoleon abdicated.

After taking part in the Allied victory at Toulouse in April 1814, the 1st Life Guards proceeded to Bordeaux, then on to Boulogne. After arriving in Dover in early July, they returned to their Hyde Park Barracks, London.

With the Treaty of Fontainebleau signed and Napoleon exiled, they started to enjoy the hard-won peace. This was not to last, as in May the following year, their services were once again called upon, this time in Belgium.

Waterloo

The Treaty of Fontainebleau had basically exiled Napoleon on the island of Elba and gave him ‘complete sovereignty and ownership’ of the island for the remainder of his life. Not all countries believed Napoleon would settle for this and feared he would try to return to France. He did just that in February 1815. After landing near Cannes, he marched onwards to Paris, rallying an army around him, and by March, he had reached the capital. This caught the British and the Allies totally off guard. The belief in peace meant many soldiers had been discharged, leaving their armies depleted of the large fighting force then needed.

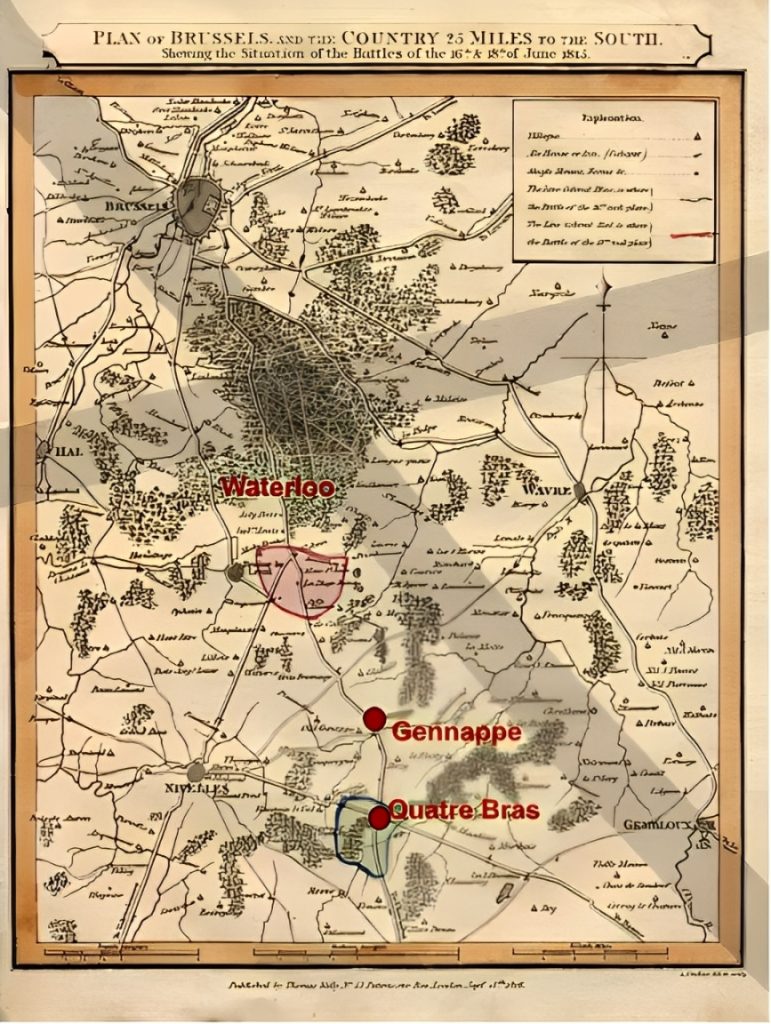

At Quatre Bra, on June 16, the hastily formed force of British, German and Dutch forces succeeded in holding the French Army. The next day the 7th Hussars enabled the army to get through to the village of Genappe and were ordered to hold the village and prevent a French breakthrough but, unable to do so, they disengaged and the French Lancers pursued them. At this point the 1st Life Guards, Stephen amongst them, were called into action

Lord Uxbridge, Wellington’s second in command, ordered Captain Kelly to charge the French. The men of the Life Guards were all in excess of 5ft 11inches tall. Mounted on their large black horses they were a spectacular ceremonial sight. Charging towards you in battle they must have been terrifying. The ferocious fighting that followed drove the French back through Genappe.

Once relieved they were able to rest but the call for action had been so sudden they had only what they could carry in their packs. With the chaos and turmoil of the battle going on around them, food and water could not be brought to them, leaving the exhausted men suffering from hunger and thirst. “…We passed this night in a wood without provisions or liquor and nearly up to our knees in water…” wrote Private James Wilson after the battle. The wet weather conditions had also left the men and their horses covered in mud.

The battle which commenced on the 18th became known as The Battle of Waterloo. Private James Wilson wrote “…on the 18th came on that Battle which I shall remember as long as I live Surely there could never have been one more obstinately contested. The Enemy must have I think four Guns to our one, for eight or ten hours on an immense Plain the shot and shells flew among us oftener than the strokes of a clock pendulum. We charged several times this day …”

Injured and wounded men were first treated near the battlefield then sent to Brussels. Travelling the ten miles in carts, walking or on horseback, to get further treatment must for some have been excruciating. As Stephen only suffered ‘injuries rather from being wounded he may well have been spared that terrible journey to Brussels.

Following the allied victory the men took stock and later they would have been relieved by the amnesty given to those who had lost equipment in the battle. They would normally have expected their pay to be docked to cover the costs or even punished for its loss. All surviving soldiers were awarded two years’ seniority. For veteran soldiers, like Stephen, this meant they could retire two years early on a full pension. They also received prize money.

Prize Money

Prize money, more often associated with the navy, was used as an incentive for soldiers to fight hard and force the enemy to flee, abandoning their baggage trains and personal possessions. This would be collected and sold with the resulting money distributed amongst the soldiers depending on their rank.

The prize money from Waterloo was huge. In total it amounted to £978,850-15s-4d. (over £63 million today) of which Stephen, as a Private, would have received £2-11s-4d (approx. £200), Sergeants £19s-4s-4d each, Captains £90-7s-3d, Field officers £433-2s-4d and Generals £1,274-10s-10d. The Duke of Wellington received £61,178-3s-5d halfpenny (about £4.9 million today)!

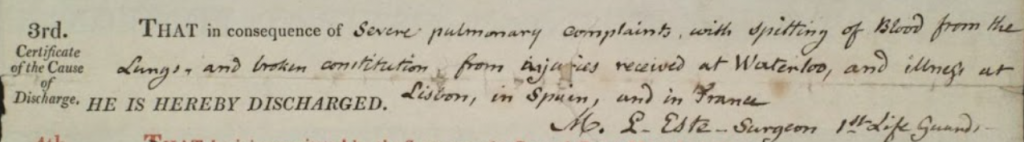

Discharged

After Waterloo Stephen returned to life at Hyde Park Barracks. On September 21 1816 William, Stephen and Elizabeth’s first child was baptised in St. James’s Church, Piccadilly. Stephen was still then a serving Guardsman. Sadly William died within months of his birth. In 1819 a second son, Henry was born and their daughter Elizabeth, was born in August 1821, Stephen had left the army and had gone back to his old trade as a watchmaker. Watchmaking didn’t last long as by the time their last child, another William was born in 1823 and who also died young, he was a labourer.

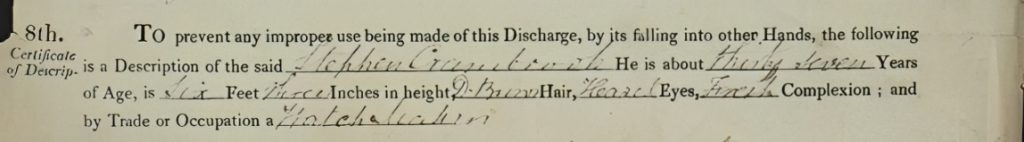

Stephen never fully recovered after Waterloo which led to his discharge on June 24 1820. His Statement of Service details his illness and general condition of ill health. It also describes him as thirty seven years old, 6ft 3 inches tall, with dark brown hair, hazel eyes and a fresh complexion. The description of a discharged soldier was given so if lost or stolen, it could not be used to make false pension, settlement or business claims. An Act of Parliament had been passed in favour of discharged soldiers enabling them to set up in a trade where they could rather than having to return to the parish of their birth.

We know that in 1841 Stephen, Elizabeth and their daughter were all living in Trevor Place in Westminster where Stephen is listed as a Pensioner. Stephen’s health continued to deteriorate and in March 1845 he died. The cause of death was given as ‘Natural Decay,’ he was sixty four years old. Elizabeth remained in their Trevor Place home, living with her married daughter and her family, until her own death in 1854. The 1851 census tells us that she had been working as a laundress to support herself.

The Waterloo Medal

The London Gazette on 23 April 1816 announced that every British soldier who fought at Ligny, Quatre Bras and Waterloo would be awarded a silver medal. Previously campaign medals were only ever given to officers. The medals were produced by the Royal Mint, each with the soldier’s name, rank and regiment stamped on the edge. The recipients became known as ’Waterloo Men.’ Not only was this the first time that all soldiers received a campaign medal but it also was the first campaign medal to be awarded to the families and next-of-kin of soldiers killed in action.

Having fought at Quatre Bras and Waterloo, Stephen was one of the 40,000 men who received the Waterloo Medal. What happened to his medal is not known but at least the story, of Deal and Ringwould’s very own ‘Waterloo Man,’ Stephen Crambrook, has been saved and can be told.

| Name | Born | Baptised | Married | Died | Buried |

| Stephen Crambrook | 1784 Ringwould |

August 8 1784 St. Nicholas Church Ringwould |

Elizabeth Piddock St. Marylebone Church, Westminster end of 1807 Born 1786 |

March 2 1845 1 Trevor Place, Knightsbridge |

March 8 1845 Holy Trinity, Brompton: Brompton Road |

The Children of Stephen Crambrook & Elizabeth Piddock

| Name | Born | Baptised | Married | Died | Buried |

| William | September 21 1816 | November 30 1816 St James, Piccadilly | 1817 | April 24 1817 St. Lukes, Chelsea |

|

| Henry | May 13 1819 | June 6 1819 St James, Piccadilly | 1.Elizabeth Staniforth September 20 1841 St Peter and St Paul Cathedral,Sheffield 2.Eleanor Dally All Saints, Ennismore Gardens, Knightsbridge |

||

| Elizabeth | August 10 1821 | September 9 1821 St James, Piccadilly | John Wrighting March 27 1842 St. Nicholas Church, Brighton |

1863 | |

| William | September 16 1823 | October 10 1823 St James, Piccadilly | 1829 | January 4 1829 St. Lukes Church, Chelsea |

Census

| Year | Address | Name | Relationship | Occupation |

| 1841 | 1 Trevor Place, Knightsbridge | Stephen Crambrook | Head | Pensioner |

| Elizabeth Crambrook | Wife | |||

| Elizabeth Crambrook | Daughter |